Is there any better movie experience than the film festival at Auckland’s opulent cathedral of cinema?

A trip to the cinema can be transcendent. There are “great similarities between a church and a movie house”, reckoned Martin Scorsese, who once imagined he’d be a priest but went another way. “Both are places for people to come together and share a common experience, and I believe there is a spirituality in films.”

You know what he means when you go to the Civic. Sat squarely, handsomely in the centre of Auckland city, this is our cathedral. There is nowhere more awesome, more breathtaking, transporting, spectacular, to watch a movie in New Zealand. That much was obvious to everyone there last night. Two thousand people got swept up in and swept away with We Were Dangerous, a vivid, funny and viscerally timely new New Zealand film.

You could and should see We Were Dangerous anywhere you can. But if you’re really lucky, you get to see it at the Civic. Since it was lovingly, expensively restored in the late 90s, the theatre has been equipped to host musicals as well as film, and there have been some spectacular shows mounted since (Mary Poppins sailing to stage on a flying fox above the audience is a personal highlight) but at heart and origin this is a hall of pictures. You can feel the lungs of the Civic filling when the film festival comes around.

Opened to fanfare in December 1929 (and therefore today on the brink of a telegram from the King and a glorious birthday), Tāmaki Makaurau’s “wonder theatre” was born in the golden age of cinema, and is today one of just a handful of remaining “atmospheric theatres” – the sole survivor, they say, in the southern hemisphere.

If “atmospheric” sounds a bit kooky, well, yes, it’s that. Good kooky. Kooky on a giant, unabashed canvas. Spellbinding kooky. Even before the first frame is projected, you’re in a kind of fantasyland. Through the foyer and along the labyrinth of linked hallways stalk a menagerie of elephants, horses, panthers, monkeys and crocodiles, spilling out of the friezes and minarets and chandeliers. In keeping with the Indian-inspired theme, several Buddhas cast gaze disapprovingly at latecomers.

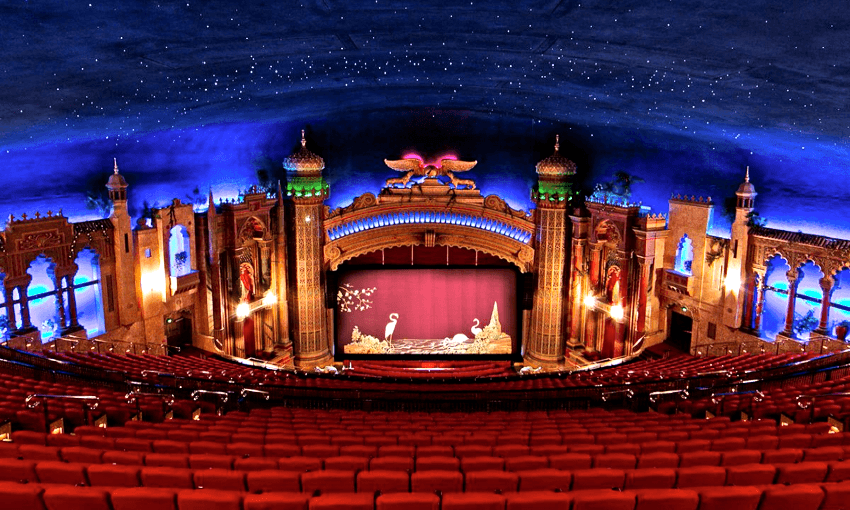

Inside the cinema itself, a trio of flamingoes stare out from a giant curtain you want to curl up in. (After the original flew to Kapiti, a group of legends painstakingly stitched together a replica, which was hung in 2000.) Guarding the giant cloth are a pair of lions crouch, their eyes ablaze in vicious opal. “I got told off for climbing a lion,” said director Josephine Stewart-Te Whiu – a name you should get used to hearing – introducing We Were Dangerous last night on the stage of the cinema she venerated as a child. “I kind of want to say to that usher, take a look at me now.”

What a place to show your film. Above, past the green glowing spiral towers, beyond even the big cats and mad winged globe that perch above the proscenium arch, is an epic starscape, complete with rolling clouds. Even though I know it’s there, every time I go my head tilts inexorably back, as it did again last night, like a gaping fairground clown.

Who knows what was going through the minds of Australian architects Bohringer, Taylor, and Johnson when they designed this thing in a hurry, a mishmash of inspiration under commission from the effervescent developer Thomas O’Brien, who got the Civic built, incredibly, within eight months. (Alas, things went awry for O’Brien; he was bankrupted not long after, and legged it to Australia.)

“One gets the idea of an Eastern potentate’s palace,” was the impression of the Auckland Star in December 1929 upon walking into this newly opened “wealth of ornament”.

It continued: “There is not one feature that is reminiscent of the usual place of entertainment. Rather one imagines that he is in foreign lands, and he almost feels inclined to clap his hands in the Oriental way, to see if he cannot summon the genii of the Ring or the Lamp, who would bow before him and execute with impossible celerity his wishes, no matter how fantastic.”

I might give that a go this week. The place is flamboyant, phantasmagorical, gloriously and giddily silly. I love it, and every time I go I notice something new. The Elephant Bar, the Boro Bodur Bar, the Safari Room, the Taj Mahal Room; downstairs to the Wintergarden, which has seen a few things in lives as tearoom, ballroom and nightclub frequented by American sailors.

All of that could so easily have been lost. Through the 1980s, the Civic was showing its age. It was a struggle to get audiences in, and the spectre of demolition loomed. As part of a campaign to save the theatre, Auckland arts titan Peter Wells made The Mighty Civic. “There would be an international outcry if Vatican City authorities decided to demolish the splendour of Michelangelo’s ceiling in the Sistine Chapel,” began one newspaper report on Wells’ film. “Unless action is taken, a ceiling some regard as the most precious in New Zealand faces this fate.”

Wells described his own transcendent experience as child in the 50s, which began with the thrill of going in to town on the tram. “Waiting for me on the crossroads of Queen Street,” he said in the film, “was an enchanted castle where everything ordinary was left behind.”

Another Civic champion was Bill Gosden, who ran the NZ Film Festival for three decades, and whose spirit, alongside Wells’, can be spotted glimmering through a constellation in the ceiling if you know where to look. He called it “the grandest venue we’ve ever known”.

Bill fought hard over many years to ensure not just that the Civic survived but that it survived as a cinema. In his souvenir programme introduction for the film festival in 1996, with the future of the venue hanging in the balance, he exhorted the council to “protect – and radically enhance – its role as a glorious setting for the big-screen, big-crowd experience. It’s an experience some of us consider one of the essentials of civilised life.” Happily, they were listening.

These days the opportunities to watch movies at the Civic are few, mostly limited to big premieres or the midwinter congregations of the NZ International Film Festival. If you haven’t seen a movie at the enchanted castle, I urge you to try it; you won’t regret time spent with the elephants and flamingos under the stars.

The place is humming, glowing and warm, unforgettable on a festival night, as it was last night. It’s a different kind of magic in the daytime. There’s no tram to catch, alas, but to sneak away from ordinary life in the morning, slip into the giant Civic, ideally taking a risk on a film you know nothing about, buzz out at the inside-sky and soak up the huge screen – there’s no feeling quite like it. It’s as though you might just have clocked the universe.

Toby Manhire is a NZ International Film Festival trustee. The festival opens in Auckland on Wednesday August 7, is under way in Wellington, opens soon in Christchurch and Dunedin and continues around the country. More details here.