Auckland’s best live music venue is feuding with the world’s biggest promoter. Only one side is willing to speak about what happened that fateful night in April.

The artist is dressed in black, with a DJ and live drummer, and the crowd bobbing in unison to sinewy R&B. Footage from 6lack’s concert suggests it was just another Wednesday night, sublime and routine at a venue which many believe is the best in the country for seeing artists in that sweet spot between early fame and ubiquity. Only, it wasn’t just another show. Behind the scenes, long-running tensions boiled over between the venue’s owner, Peter Campbell, and the promoter, global giant Live Nation.

That night in April was the last time the promoter would run a show at the venue, with Campbell and Live Nation now in a prolonged standoff. Shows which Live Nation had previously announced for the Powerstation moved to other venues, without a public explanation being offered. These included Sleater-Kinney, which moved to the Tuning Fork, and Baby Gravy, who played at the Studio. These are both less prestigious venues – and the Tuning Fork is much smaller, with a limit for 400, versus 1,000 for the Powerstation.

What caused the rift remains a little opaque. A spokesperson for Live Nation asked for a “reasonable timeframe” to reply, but missed multiple deadlines for comment. Music industry sources suggested an altercation between Campbell and a Live Nation representative, culminating in their being ordered to leave the venue. Later, another Live Nation staffer received a barrage of complaints from Campbell, largely about the conduct of their colleague. Since then, nothing.

Only Campbell has been willing to go on the record about the incident and its aftermath, meaning it’s only his version of events The Spinoff can convey in this story. That said, interviews with a half dozen sources from across the live music sector essentially back up his version of events. What differs radically are perceptions of how justified he was in his actions.

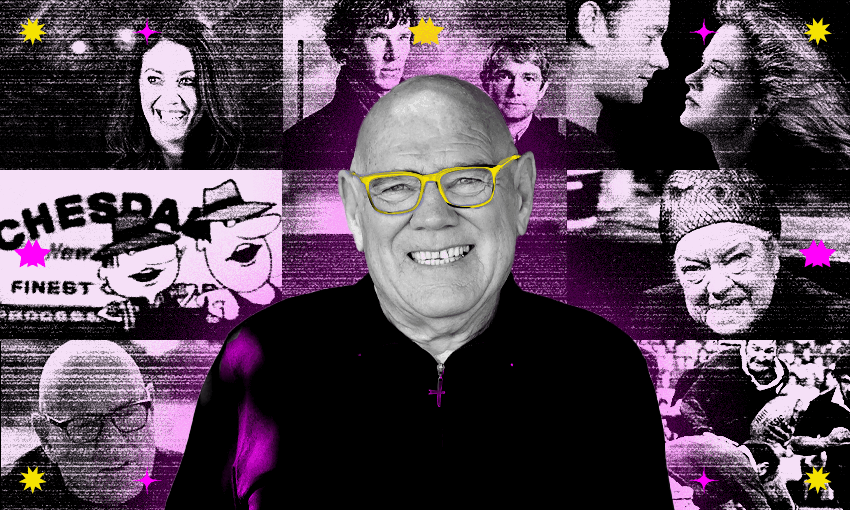

Campbell is a complicated figure. He is commonly seen as a brilliant operator who sweats the details a little too much, while others view him as far too tightly wound, especially for a space as fluid as live music.

Some say Live Nation pulled out of the venue, while Campbell says he will no longer accept their bookings. You can’t fire me, I quit. Either way, it’s a deep and sustained rift between the world’s biggest promoter and Auckland’s best venue. Beyond Campbell, no one I spoke with was willing to be named, due to acute sensitivities in the small, close knit music community. That’s understandable, in what is literally a gig economy, in both senses of the word. No one wants to get on the wrong side of either party, and there are elements in the background which bring added tensions to an already charged situation.

According to Campbell, 6lack “had a great show and enjoyed themselves. Sold it out.” There were issues behind the scenes, though, and trouble centred on the venue’s green room. This is the backstage area reserved for artists, to which access is typically tightly controlled. He says Live Nation staff were flouting his rules around the area, actions he says are typical of Live Nation’s “complete disregard” for the way he hires out the venue.

Campbell has a system, and believes it should be adhered to, and says it’s about looking after his audiences. “There’s certain things that happen around some acts,” he says. “I can’t go there because it’s not something I really want to have discussed in a broad sense, because it doesn’t reflect well on our industry at all… It’s about backstage etiquette, about keeping people safe, more than anything.”

He says his rules were repeatedly violated that night, and he had a heated discussion with one of Live Nation’s representatives. According to Campbell, the Live Nation rep had no respect for his venue, nor the rules under which he allows access. “They said I was lucky to have Live Nation shows in this venue”, which he found hugely arrogant. It was doubly offensive, he says, because “this person showed through their actions that they were reasonably incompetent”. Campbell says he ordered them to leave the venue after the argument, before the scheduled end of the show.

Later Campbell remonstrated with a second Live Nation representative at length. He says that person was not themselves at fault, but that the issues were sufficiently troubling that he felt he needed to convey them. He also says that he lacks a channel to communicate with Live Nation in New Zealand – the shows are mostly booked through the Australian office, with whom he says he works well. “I’ve never dealt with the New Zealand office, which is a good thing, as far as I’m concerned.”

The lack of a relationship was what prompted the heated remarks to the second Live Nation representative. He says he wanted to convey the seriousness of the problem. To Campbell it connects up to what he believes are longstanding issues with Live Nation at his venue. These include “walking away from contracted shows… which they did on numerous occasions, and they’re not expecting to pay any compensation for it.”

There’s also a vexed issue around VIP tickets. These are a relatively recent phenomenon, in which promoters offer pricey and limited packages that will give some fans the chance to meet the artist, or watch soundcheck, along with exclusive merch or other benefits. Campbell views them as a blight on the industry, but accommodates them where possible – but only under specific terms. He says that Live Nation representatives have repeatedly violated their contract to hire the venue through the way they run VIP packages.

All of Campbell’s claims were presented to Live Nation for comment numerous times. At time of publishing, the promoter had offered no formal response.

Issues between promoters and venues are not uncommon. There are multiple venues in Auckland which promoters say they avoid or flat out refuse to book, due to issues with the people running them. These are typically around reliability or quality – but the Powerstation is very different, in that the issue is personality-based, rather than to do with the venue itself. No one disputes that it is an extraordinary place to see music – “it’s a perfect venue. It sounds good, it looks good, it’s very efficiently run”, says one promoter. Its combination of layout, compact but ample size, acoustics and infrastructure make “just such a pro setup”.

It’s this quality which has made it an unrivalled institution within the city, a place generations of music fans have had formative memories burned into their synapses. A venue since the ‘50s, it’s hosted some of the most hallowed shows in our live music history, including performances by Radiohead, Kendrick Lamar and Odd Future. Local artists revere it, with the likes of Lorde and Six60 taking the stage despite being able to fill vastly bigger venues.

Yet there is a paradox with the venue, say some who’ve used it. They admire Campbell’s attention to detail and work ethic – one says they regularly see him mopping up in the early morning, the last person working, after a big show. Yet he can be “curmudgeonly and inflexible”, says one source, while another describes him as “intensely hands on”. They describe a moodiness which has people on tenterhooks. “He’ll be really personable, or tell you to fuck off.” Another says “he’s competent and always pays his bills, he’s just really weird”. Some say this behaviour accelerated after the death of his partner, with whom he owned the venue, in 2020, while others say the issues stretch back a decade or more.

One source describes Campbell as closely resembling the Seinfeld character the Soup Nazi. He runs an incredible venue, but is a massive pedant. They are at pains to point out his staff are uniformly great people, and that for the most part any issues are isolated to those who’ve booked the venue, and that artists and audiences generally have great experiences there. That’s not always the case, though – the Herald reported last year on a run-in with a fan, who Campbell was annoyed at for waiting outside the venue well ahead of doors opening.

On the other side of the dispute is an equally complex character, one a prominent Australian band manager called the “death star” of the music business. Live Nation is a vertically integrated monster, with tentacles throughout the concert business – it owns major ticketing companies, festivals (including Rhythm and Vines), promotes large and small tours, and often has exclusive rights to book venues. An industry source, who asked not to be named due to business relationships with the company, says “there isn’t an ecosystem anymore. It’s just one [business] controlling everything. And that’s not a healthy way to operate.”

Live Nation also owns venues, including Spark Arena and San Fran in Wellington – a venue which plays a similar role to the Powerstation in Auckland. Some sources I spoke to speculated that Live Nation would be a natural acquirer for the Powerstation, were Campbell to ever want or need to sell it. But for all the suspicion of Live Nation internationally, in New Zealand it’s run by people. Those individuals, from MD Mark Kneebone on down, have worked in the industry for decades, and are well-liked and respected by most, irrespective of the entity they work for.

The feud lingers on. There are no Live Nation shows booked at the Powerstation, despite other promoters regularly announcing shows, and Campbell says bullishly that Live Nation’s absence has had no impact on his business. This might be just posturing, as he admits 2024 has seen significantly fewer bookings than 2023. There’s also fresh competition – Double Whammy is now open on Karangahape Rd, a superb new venue built out of two old ones, which can hold 500 people.

It’s a tense and unfortunate situation, without a clear villain. Campbell and Live Nation have been in disputes before, but none like this. The longer it continues, the more likely it seems that Auckland’s best venue will be permanently closed to the world’s biggest touring company.