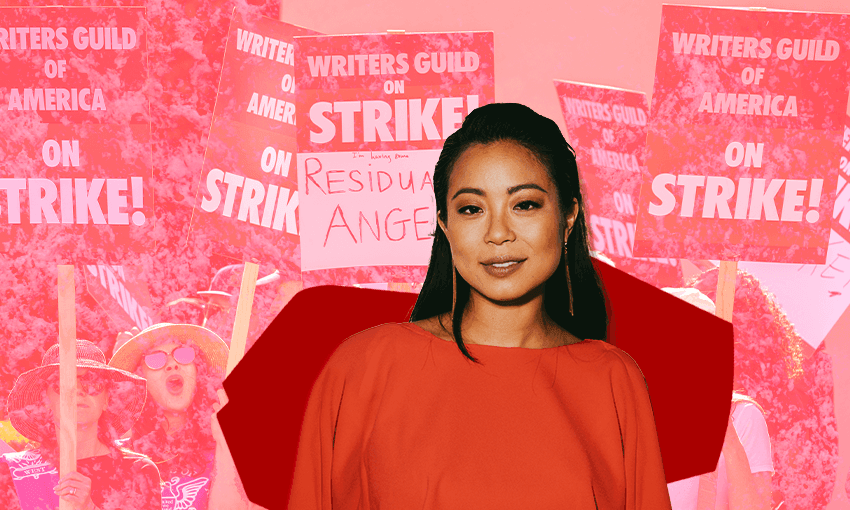

Michelle Ang has joined the picket lines in Los Angeles as striking writers shut down America’s film and TV industry.

When Michelle Ang visits Los Angeles, she usually meets friends in cafes, or attends meetings at TV and film studios dotted around Hollywood. This time, those catch-ups have had a different vibe.

“The best time to have a chat and spend time and be useful is to join them in the picket line,” she says. “I was doing catch-ups and picketing at the same time.”

Ang, a veteran New Zealand film and TV star who works behind and in front of the camera, spent several hours protesting outside Paramount Studios this week. Alongside her were some very big names. “There are all kinds of people,” she says. “People are driving by and honking. I looked over at one point and was like, ‘That’s Christopher Nolan.’”

Right now, Hollywood’s TV and film industry has pretty much shut down as 11,000 writers go on strike. Members of the Writers Guild of America spend their days in front of studios waving signs like, “Here’s a wild pitch: Pay us!” and “We have some notes!” to protest conditions, pay and the diminishing role writers are playing in the peak TV boom.

Some say they’re striking to protect writing as a viable career. “This is an existential fight for the future of the business of writing,” one told The New Yorker. The WGA is at odds with the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers over several other issues, including the rise of AI in the writer’s room, the creation of “mini-rooms” that employ fewer writers to do more work, and the lack of certainty in their chosen careers.

Ang, whose long list of credits includes Neighbours, Fear the Walking Dead and Star Wars: The Bad Batch, says everyone’s talking about how much the TV landscape has changed in the streaming era. “Contracts were structured to really favour the main broadcast networks. That’s how you would make a good fee,” she says. “Then, [writers] would get residuals (money from repeats, or international sales) that you could live off. You’d probably get one, two, maybe three jobs a year max if you’re lucky, and you’d get residuals.”

That would be enough to keep writers going through leaner times. Now, with streaming, they just get paid once per job with no certainty on when their next one will come. It’s always leaner times. “The compensation for streaming is significantly less and residuals … they almost don’t exist,” says Ang. “There’s a real dissonance of how corporations are making money. And that needs to be updated.”

Last time this happened, in 2008, seasons of hit shows like Breaking Bad, 30 Rock and The Office were cut short, big budget movies like Transformers and Quantum of Solace were re-written on set, and late night hosts were left to fend for themselves. In one famous scene, Conan O’Brien spent more than a minute twirling his wedding ring to fill airtime.

Ang says that the mood on the frontlines is buoyant, but this strike feels different to the one in 2008. “Everyone is talking about it … they’re really supportive of it and feels like they’ve got the stamina currently,” she says. Unlike last time when they forged on while writing their own material, late night talk show hosts have gone off air immediately, and many have spoken out in support of their striking writers.

But, two weeks in, predictions are that this one could go longer than 2008’s strike, which lasted 100 days. Ang heard this from a friend who has been on strike before. “He’s like, ‘Watch, it’ll get harder … this is going to be a long one, at least three months or so,’” she says. “That’s going to be hard to weather for some people.”

Ang is there to promote her work on the anthology film Kāinga, but she says the city feels much quieter than it normally is. “No one can do development, everything’s on hold,” she says. It all depends on the strike. “Everyone’s waiting to see how long it’s going to be.”