Alex Casey chats to David Lomas about the art of finding needles in haystacks.

There are around 100 people scattered all over the world who are members of a very unique and exclusive club. All of them, at some point over the last 16 years, have had a knock on the door and discovered a bunch of mystery flowers on their doorstep. A secret admirer? Congratulations? Condolences? Cautiously opening the small, handwritten card beneath the blooms, they all would have slowly processed the same words.

“Hello, I’m David Lomas. A relative of yours in New Zealand is trying to contact you.”

Despite everyone being glued to their phones, and social media making people more accessible than ever before, sending flowers remains one of the most effective ways of getting in touch with a stranger, says the host of David Lomas Investigates. “People will always be intrigued by flowers,” he says. “It gets delivered right to their door, you can put a little message on it with your email and phone number, and we often get fast replies.”

The technique works as effectively in Ōtautahi as it does in Hungary. “There was a woman in New Brighton that I was trying to get a hold of, but I didn’t have her phone number,” he explains. “So I just rang the local flower shop and asked them to drop her some flowers.” She called him back that evening. “It’s a pretty quick way of finding someone if you can’t knock on their door yourself,” he smiles. “It’ll just cost you 50 dollars.”

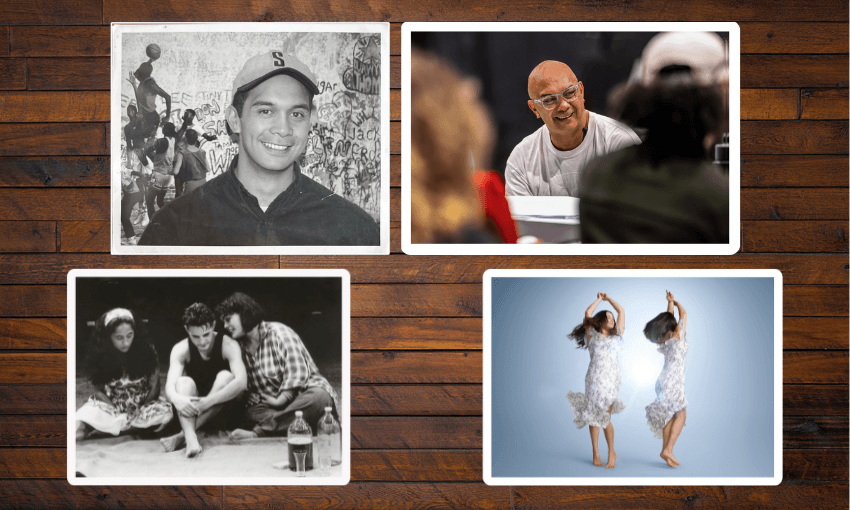

That person is just one of hundreds that have been contacted by Lomas over the 15 years he has been fronting his own docuseries, iterations of which have included Missing Pieces, Lost and Found, and more recently David Lomas Investigates. But while the titles have changed, the brief has broadly stayed the same: Lomas works with a subject, referred to in-house as a “seeker”, to help them connect with someone from their past.

Around 12,000 people have contacted Lomas since Missing Pieces began in 2009. Applications go through a strict vetting process, where the vague (“my mum had an affair in the pub, she can’t remember his name”), the impossible (“the only name she has is Mohammed”) and the too easy (“my dad lives in Palmerston North”) are sifted through by associate producer John Keir and genealogist and researcher Gail Wilson-Waring.

The remaining seekers are then graded from one to five – “if it’s a five, it’s a fantastic story” – before more careful metrics are considered such as region, gender and ethnicity. “We’ll always look at the balance of the programme,” says Lomas. “We struggle to have a balance of male seekers, it’s probably 80% women, and we do want to be sure to demonstrate the different cultures in New Zealand and people who live here.”

From there, the search commences. Lomas has an impressive contact book of people with local knowledge and language around the world, some of whom were previously involved in the show, who help to ring around. “It’s obviously a massive amount of work, so we give them clues as to how best to find someone. For example, if we’re looking to see if someone’s alive, you ring rest homes,” he pauses. “And then you ring funeral homes.”

You’d think social media would make the job easier, but Lomas says this is far from the case. His messages can often sit unread for months in people’s ‘other’ inbox on Facebook, but he says the friends list can provide helpful back avenues. “You can trawl through someone’s friends list, find the most unusual name amongst all those friends, and then you’ve got a fairly good chance you can track that person down at least.”

Ringing people is a challenge too. “Most people are really distrustful of people who try and ring them – especially if you’ve got an international number,” he says. “We’re constantly battling to get people to actually answer their phones.” Lomas once rang an overseas subject 20 times until they finally picked up and yelled “why do you keep on calling me”, leaving him a very short window to try and explain.

That’s why, ironically, snail mail and flowers remain the most reliable methods. Those early messages are always “honest without saying too much”, says Lomas. “We probably wouldn’t say the seeker’s name in the very first communication, but we might say ‘does the date December 16, 1956 mean anything to you?’ You do try to be delicate, because it’s massive for both sides. When we approach a person, it’s generally one hell of a shock.”

“People always joke that they hope I never contact them. Because for blokes, it’s probably the child they never knew about. And for women, it’s probably the child they’ve never spoken about.”

Despite appearing as the ghost of secrets past, it’s not often that he’s told to get lost. “The most frequent people who don’t want to deal with us are mothers who have given a child up for adoption, and gone on to start a new life,” says Lomas. “That’s a heck of a thing to come back from.” People often want to be connected, but not on camera, which he says is “perfectly understandable” too. Other times, the trauma is simply too great.

Some searches can be completed in a day, and some take years. Lomas recalls a particularly challenging story from the first season of David Lomas Investigates, which involved a Tokelauan man who became the pride of his family after moving to Rome to become a priest. But after experiencing abuse within the seminary, he was too ashamed to return home, instead turning to “a dark world” on the streets of Rome.

Eight different family members contacted Lomas, and for five years he was faced with a needle in a haystack until some fortuitous scrolling on RNZ. “We saw an article which mentioned a Samoan woman living in Rome, whose family had connections with lots of people,” he says. “We knew that Tokelauans and Samoans are fairly close, so we just thought maybe she’d heard of this guy. That’s how we eventually got there.”

Of all the stories he’s done, Lomas says that Rome trip was “staggering” for everyone involved. “We took his sister over to meet him, and she just cried and cried and cried.” Does Lomas ever join in the waterworks? “I’ve got to control my emotions while I’m doing it, but that doesn’t mean I’m not feeling it,” he says. During reunions, he’s often filming himself on his “trusty little cellphone”, so engaged differently in the scene.

“When you get so involved, you almost forget you were actually there,” he explains. “Often I’ll come across old episodes being replayed on telly and I’ll think ‘crikey, that’s fantastic’.”

In a time where journalism is in crisis, Lomas says it is an “absolute privilege” to still be telling New Zealand stories. “It’s absolutely devastating,” he says of the recent current affairs closures at TVNZ and Three. “I was involved in starting Sunday, so to see that thrown out is really sad. We have a minister of broadcasting who seems to have scant interest in what is happening,” he adds. “It’s bad for everything about New Zealand.”

David Lomas Investigates is currently airing on Three, and has funding for another eight episodes, but the future beyond that is unclear. Whatever happens, he’s grateful to have had a role in showcasing a wide range of New Zealanders in prime time. “One of the the magic things is that we go into people’s homes and their backgrounds, and tell stories which bring about a lot more understanding about the lives they’ve had to lead.”

It’s also been a space to shed light on painful parts of both our shared and personal histories. “People walk up to me and say ‘I’ve never talked about this before, but I gave a child up’, so I do think it has helped to change attitudes.” For all those hours of unanswered phone calls and enormous florist bills, he hopes the programme has shown that all kinds of New Zealanders can experience trauma, loss and, most importantly, hope.

“None of it is anything to be ashamed of,” he says. “It’s all life.”

Watch David Lomas Investigates 7.00pm Tuesdays on Three, or here on ThreeNow