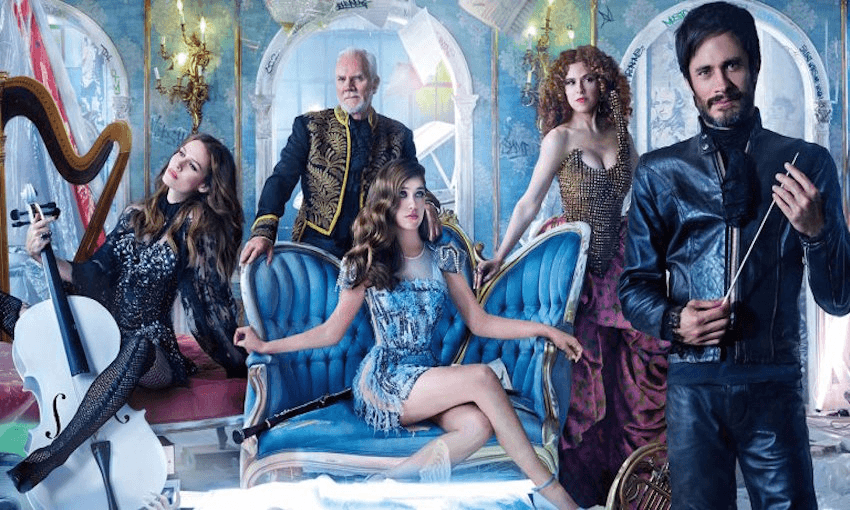

Season four of classical music comedy Mozart in the Jungle drops tomorrow on Lightbox. Longtime fan of the show Sam Brooks decided to read the book it’s based on and compare the two.

Contrary to its title, Mozart in the Jungle is not a television show about the world’s best composer (according to people who know anything about classical music, so not me) roaming around in a hot jungle.

What it is about is the lives, loves and professional struggles of classical musicians in New York. It’s billed as a comedy, but it navigates and flips it way around being a workplace comedy (if your workplace was the hollowly glamourous world of a symphony orchestra), a will-they-won’t-they drama and a scathing critique of the high-falutin’ world of classical music.

What Mozart in the Jungle also is is that it’s based on a book from about ten years ago, which shares the same misleading title: Mozart in the Jungle: Sex, Drugs and Classical Music. And in my wild and rampant anticipation for more of this bizarre and beautiful little series – seriously, a show like this wouldn’t have happened ten years ago and we’re lucky that streaming services are dipping their fingers into passion projects like this – I decided to read this little memoir and see how it compares, especially in its depiction of the world of classical music (and I also read it so you don’t have to, because books are hard):

Classical music is full of dicks

The show, as it will be hereafter referred to, does a really great job of giving us likeable characters (Gael Garcia Bernal’s Rodrigo is absolutely someone who might grate on you in real life but I could watch him mispronounce ‘Hailey’ for literally a hundred years) and putting them through the ringer while not making it too bleak to bear.

The book, as it will also be hereafter referred to, has no compulsion or desire to give us likeable characters, given that it is based on real life. This will be a shock to some of you, but often enough, there are very unlikeable people in real life, and those people have nobody writing them to make sure they don’t come off as dicks. They’re just dicks.

Many of the classical musicians that fill Tindell’s memoirs are egotistical, depressing and narrow-minded people. A particularly tragic character is Sam, a chronically and terminally ill accompanist who does Tindell wrong after she takes care of him after a heart transplant; he literally thanks everybody for being around him except her, the only person who appeared to have been around. It’s the kind of moment that makes you close your book and shake your head.

Classical music is horny

If Tindell’s book is to be believed, and as someone with next to no knowledge about classical music, I’m inclined to believe it, classical music is top-to-bottom full of people having sex with each other, their partners and any other person who even appears to have touched a violin in their life. It’s wild, and Tindell portrays it in the least sexy way possible, which is understandable given how bleak many of these encounters are (many of them read like shorter versions of the New Yorker‘s Cat Person story).

If the show is to be believed, it’s more full of people falling in love and not being able to do anything about it, which is infinitely more watchable (though people do have sex, and it is awkward and weird). If I wanted to watch a show about mean, sad people fucking, I’d go back 12 years and stay up late to watch Nip/Tuck at a low volume, hoping my mother didn’t hear what was going on. Thank you for restoring my belief in awkward not-quite-love, Mozart in the Jungle (the show).

Classical music is broke

A huge subplot, if you can call a constant stress in someone’s life a ‘subplot’, that runs through Tindell’s book is how broke she constantly is because of her profession: she has to work multiple jobs, and when she actually gets a stable job in the orchestra of a Broadway show, Miss Saigon, it comes at a cost: It means she’s effectively cut off from doing the more lucrative and more prestigious classical gigs. Classical music had the gig economy before we’d even heard of it – people running their bodies and souls into the ground just to make a buck. It makes for engrossing, if bleak, reading.

Thankfully, the show doesn’t show us this! Which is nice, because broke people aren’t fun to watch on TV, unless they’re on Shameless, and even then it’s a little bit sad. What it does show us is that classical music is not a business, and has been in the process of constantly losing money for at least the past 50 years, or as the Bernadette Peters-played symphony manager says: “It’s been losing money for the past five hundred years.”

Classical music is the worst

One of the best things about this book, and indeed any book that demystifies and deglamourises industries that tend to be put on a pedestal, is that it reminds us that any art form is a profession and a craft. And with any profession and craft comes a lot of busywork.

The book Mozart in the Jungle is like a reverse love story. It shows Tindell slowly falling out of love with classical music as she is beaten down by the demands of the industry around her, the people, the constant poverty, the lifestyle and the isolation that being in such an industry provides. It reminds us that for all the beauty and artistic achievement of classical music, it doesn’t mean jack if you’re not happy doing it.

The show, thankfully, does not go quite this dark or quite this bleak. But it still shows us enough of the struggles within classical music to make me never want to go into that profession (as though that might be an option for a 27 year old who cannot play any instrument whatsoever or read music). But while the book shows the descent of a wide range of people all the way down to rock bottom, the show is more gentle with its characters. People lose out on jobs, but they get back up. It’s maybe a little bit less realistic, but it’s a whole lot more pleasant to watch.

Classical music is the best

A quote that stuck out to me from Tindell’s book is this: “When my reeds were working, though, I learned that making a sound spoke my emotions more directly than my own voice.”

It’s the one gem of salvation throughout, and one that really resonated for me. That when you’re good at your art, the thing you’re passionate about doing, that can feel more authentic and more real to you than talking. In that moment the rest of the world falls away from you entirely, and this one thing makes you ignore all the bad shit – the dicks, the poverty, the bad sex, the general unbearable nature of it. It’s transcendent.

There’s a moment in the show that does the same thing, halfway through the third season. After a crazy and drama-filled rehearsal period, the Italian diva Alessandra is conducted by Rodrigo in an opera about Amy Fisher (you know, the Long Island Lolita). She recently just saw Rodrigo, the man she’s in love with, kissing another woman. And the anger, passion and fire she now brings to the role of Amy Fisher is pure, all-consuming fire. Not only do you see her do this, but you see Rodrigo realise this, and you visibly see him lift his game.

The book Mozart in the Jungle is good – it’s a super informative and snappy read for such a bleak time – but the show Mozart in the Jungle is flat out great. It takes the foundation of the book, all the facts that Tindell knows from a life lived and a life endured in this industry, and it blossoms out from it into its own thing. A more humorous, lighter and more engaging thing.

Should you read the book? Probably! It makes classical music interesting – which is no small feat.

But should you watch the show? Absolutely. It makes classical music, and the people who love it, actually compelling – which is a damn masterstroke.

The fourth season of Mozart in the Jungle drops on Lightbox tomorrow (Saturday 17) and you can watch it right here: