Shanti Mathias talks to the maker of a new documentary series about a topic a lot of us would rather not think about.

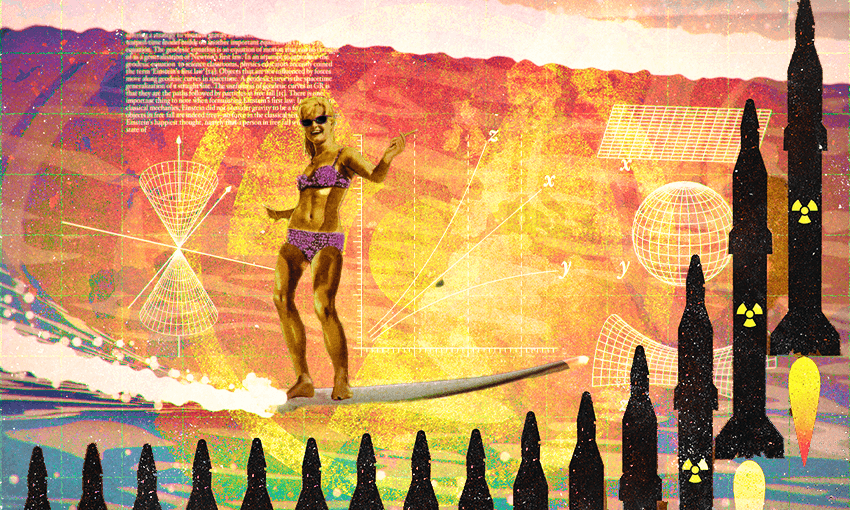

Rachel Currie wants people to think more about the future. Specifically, the bad future: in the producer/director’s new series, Brave New Zealand World, a thousand visions of apocalypse float across the screen. Ultra-deadly pandemics spread across the globe. Some of the estimated 13,000 nuclear warheads dotted around the world spin to point at enemy countries. Rising sea levels cause mass flooding and a new tide of displaced refugees. Humans develop generalised artificial intelligence which has the capacity to turn on its creators.

But Currie thinks it’s important to talk about these existential threats, the dangers which could wipe out humanity, because they’re caused by humans – and they’re also fixable by humans. “None of these problems are insurmountable. These are threats we have created, and we can do something about, even if we choose not to.” She hopes that the series, airing on Prime from this evening, will help people to look directly at these very real threats.

When contemplating the many dangers of the future, questions of scale can be difficult to grasp. Take artificial intelligence, for instance. In the short term, tools like the image generator DALL-E are remarkably powerful and fun to play with, but they’re not sentient, and don’t boast the same range of capabilities that humans easily master. “Potentially sentient, intelligent beings don’t exist today,” says Lisa Ellis, a professor of political philosophy at the University of Otago who features in the series. “So policy to address [AI risk] is a lot more pedestrian than the ethical questions of what right relationships with other intelligent beings look like.”

Instead, she says that making our social and information systems resilient to the threats of disinformation and data surveillance is a more tangible short term option. “We have really lax policies around disinformation – it’s amazing to me that things aren’t worse.” Rigorous regulation of the tech that already exists is the best way to prepare for future advances like even more powerful AI.

The problems of scale also extend to individual versus collective action to tackle future threats. “This cult of the individual contributes to existential risk, while acting collectively allows us to solve problems,” says Currie. She mentions US tech billionaires like Peter Thiel who have built themselves refuges in Aotearoa to hide from potential catastrophe, comparing them to the millions of people – mostly poor, brown, and non-English speaking – who will be displaced by climate disasters. “In the future when crises hit, the poor will be at risk, and the rich will get richer.”

Initially, Currie wanted to cover some of these inequities in greater depth in the series – to make Brave New Zealand World a kind of survival guide for the end of the world: what to pack, how to forage, what to keep in the cupboards. But “anyone can Google that”, so the focus shifted to the longer time horizon and a framework for understanding that big-picture threats are real.

For Ellis, the conflation of individual and collective risk can be frustrating. She brings up the anti-natalist movement, in which people commit to not having kids because they feel the future is in jeopardy. “It’s sad and sweet that people are taking that burden onto themselves,” she says, but wonders how not having a child can ever make up for “the 0.0001% with their private jets and three heated pools”.

As a philosopher, Ellis thinks that individual shame and guilt about contribution to climate change, in particular, is misplaced. “You can start thinking – anything I do will travel through global supply chains, through the carbon cycle, to hurt someone else. It can be so depressing and paralysing that I don’t recommend people think about it individually.” Meanwhile threats like nuclear war, unregulated artificial intelligence and pandemics will affect everyone, if unequally, yet don’t cause the same individual angst as climate responsibility.

Watching Brave New Zealand World can feel like a blur: the AI episode alone covers data surveillance, transhumanism, AI and alien life, filled with talking heads and stock videos, examples from other places. These are global problems, after all (and the production team was working with strict restrictions during lockdown) – but where does New Zealand fit into these matters of the future?

It’s a balance Currie hopes she’s managed to strike. “You can’t look at these impacts on New Zealand without looking at the impact on the world,” she says. The series uses news bulletins from the future – optimistically assuming linear TV will still exist in 2031 – to paint a bleak picture of global climate refugees and AI-enabled policing under which communities of colour are disproportionately targeted. Perhaps these transnational challenges will at first feel like distant news before eventually making their way to our shores.

The takeaway from Brave New Zealand World could be that existential threats are real and there’s no particular reason to feel confident that these problems will be fixed. But that doesn’t mean that acting thoughtfully and collectively to advocate for effective policy is futile. “Right now, you’re already interacting with everyone in the future,” says Ellis. “We have big problems – but we can do things to make it better.”