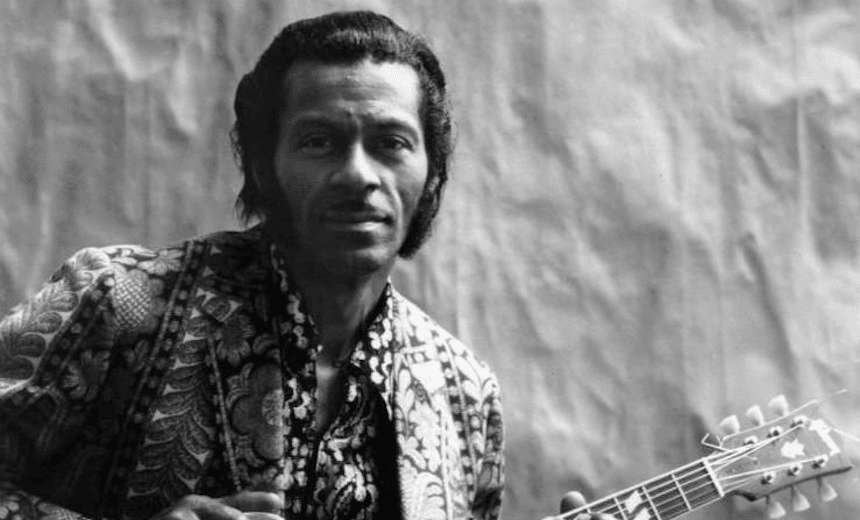

Chuck Berry died this weekend, aged 90. Nabeel Zuberi remembers the rock pioneer’s personal and musical influence.

I was nine years old in 1972 when I was first conscious of hearing or seeing Chuck Berry. His novelty tune ‘My Ding-A-Ling’ was No. 1 on the UK singles charts for what seemed an eternity. I saw him in his flared jeans and matching denim shirt on Top of the Pops for at least a month of Thursday nights. I was a slow developer, so I initially thought the song was about small bells. But before the end of that impressive chart run, several playground sniggers and ‘morals campaigner’ Mary Whitehouse’s campaign to have the song banned from the airwaves helped me to finally twig. My next exposure to Berry was primarily second-hand, through the Beatles’ versions of his songs on 1977’s Rock n’ Roll compilation. The lyric “Tell Tchaikovsky the news” from ‘Roll over Beethoven’ seemed like the perfect up-yours to high culture types, as well as justification for a serious obsession with pop music.

The ’50s hadn’t really gone away in England. In the mid-1970s, corny pop acts like Showaddywaddy and Darts churned out hit after hit of secondhand rock and roll, which sent you back to the originals. Radio Luxembourg on fuzzy, beeping AM played the oldies so you could imagine you were an extra in American Graffiti or Happy Days as you hugged the radio under your pillow. Teddy boys and their Teddy dads with their long jackets and Bryclreemed quiffs were a common sight. I wasn’t yet aware that Malcolm McLaren had transformed his Let It Rock shop (named after a Berry song) into Sex, where Vivienne Westwood designed clothes and the Sex Pistols would be brought together. In the midst of this rock and roll revival, a school friend lent me a cassette of Motorvatin’, Berry’s greatest hits compilation released in 1977 and advertised heavily on TV.

Chuck Berry should be given credit for the spread of Americana and Americanism overseas. Utopian songs like ‘Promised Land’ were detailed maps and fantasies of the open road and its possibilities. “No particular place to go” gave you the pleasure of the journey without any necessary end goal. These myths were instrumental in me going on to a BA in American Studies in England, writing an honours thesis on Sun Records, and then moving to the US for graduate school. The first time I visited the US, in 1985, I was so disappointed that the landscape wasn’t like the ones in Chuck Berry songs. Where were the convertibles with Berry at the wheel, and Jack Kerouac and Neal Cassady in the back seat? Bland strip malls had replaced the quirky drive-in restaurants and freestanding movie theatres that I’d seen in the movies and heard about in songs.

Taylor Hackford’s fine documentary about Berry, Hail! Hail! Rock ‘n’ Roll (1987), captures the colossal influence of the artist, his orneriness and the weird racial politics of American music. The film follows Keith Richard as he brings together a super-group (including Eric Clapton, Julian Lennon and Etta James) with Berry to play two concerts. Their rehearsals and the film project are dogged by Berry’s unpredictability. He is deeply suspicious. That film opened up new ways to see his career.

There was an element of the cynical troubadour about Berry with which you could sympathise to some extent. Here was a man who had been ripped off, yet he also seemed a bit of a huckster. He wrote these amazing dance tunes with that backbeat to nowhere and everywhere, aggressive guitar licks and pumping piano that would become the DNA for so much rock and pop in the 1960s. Yet he seemed to have written many of these classics because he knew they’d sell to white kids. Ike Turner, an ornery mutha in his own right, would later say this about Berry too. Here was an early lesson about that false dichotomy between art and commerce. ‘Schooldays’ is a detailed snapshot of the quotidian in and out of the classroom that couldn’t fail as an anthem for the new teenage class. No wonder that the Beach Boys would liberally ‘sample’ Berry’s songs for a number of their sunny surfin’ hits.

It’s strange now listening to some of the Berry tunes covered by the British Invasion groups. The relatively high-pitched and handclapping ‘Carol’ by the Rolling Stones makes me think of that moment in Todd Haynes’ Dylan biopic I’m Not There when the Beatles appear as squeaky sped-up boys in suits scurrying across the grass like mice. The Yardbirds’ ‘Too Much Monkey Business’ from Five Live Yardbirds sounds like lumpy heavy metal in the making, stripped of the kinetic energy that makes Berry’s recordings at Chess so infectious. Berry, Ruth Brown, Ike Turner, Fats Domino and Little Richard and many others would help to desegregate and integrate American popular culture, supported by radio stations and independent labels like Chess, Duke/Peacock, Sun and King. But the financial benefits would accrue mostly to white artists and industries controlled by white men.

No wonder then that the retro-futurism of Back to the Future would play out the ultimate Caucasian rocker fantasy of a white teenager Marty McFly inventing the new sound of rock ’n’ roll, passed on to Chuck Berry via a phone call from his fictional cousin. This was a loop that honoured Berry, yet also downplayed his contribution for the sake of boosting whiteness. The song McFly plays is ‘Johnny B. Goode’, which also happens to be a recording chosen for the Voyager Golden Records that were sent into space with the Voyager spacecraft in 1977. On Saturday Night Live, Steve Martin held up a dummy cover of Time Magazine with a message from aliens to ‘Send More Chuck Berry’. That Chuck Berry guitar sound, made in St. Louis but traversing the nation and the globe, and now in interstellar space, may be one of the most significant contributions of Afrofuturism. He’s up there now with Sun Ra, John Coltrane and the others.

All myths rely on silences and repressions. Berry had a history of abuse of girls and women. When I saw him on Top of the Pops back in the 1970s telling us to play with our ding-a-lings, he was almost certainly introduced at least once by one of the show’s hosts, serial rapist Jimmy Savile. The venerated heritage of the rock tradition and the legacies of exalted musicians have worked hand in glove with the music industry’s pervasive misogyny. To unpack how Chuck Berry’s creative drive and his will to power through territory with his guitar, car and lyrical imagination might be linked to a desire for domination presents a necessary challenge to our rose-tinted views of artists and our musical histories.

The Spinoff’s music content is brought to you by our friends at Spark. Listen to all the music you love on Spotify Premium, it’s free on all Spark’s Pay Monthly Mobile plans. Sign up and start listening today.