Come Dine With Me New Zealand’s Kelvin Taylor wants to see more African-Kiwi talent on local screens.

When I worked as a background actor in the Spartacus series Vengeance and War of the Damned, many of the other African background artists started to refer to themselves as “the blackground” on set. They were Africans who had travelled from all over Auckland, some originally from Ghana, others from Zimbabwe, Nigeria, South Africa and Somalia.

The introduction to non-unionised set life can feel daunting at the best of times, but observing such a hierarchical system in play, while we were portraying slaves on-screen, felt particularly jarring. One day, an older African woman said to me: “Without us, the show would not look historical. We are of value, even though we may never make it on TV here.”

Indeed, the programme was an American production that was not originally aired in New Zealand. Many of those background performers would never get the chance to see their work on television, despite the show being filmed in their city.

When I think of people who look like me on local television, I first think of Ajoh Chol, the only person of African descent to appear on New Zealand’s Next Top Model in 2009. During her time on the show, she often appeared isolated from the rest of the group.

In episode three, Ajoh joked that another contestant had been taking up too much time in the shower. Later, Ajoh is accused of being aggressive, and she privately concludes the reaction is due to the colour of her skin.

In the next episode, Ajoh cries while the makeover team cuts off her hair. She explains that it is against her culture, and wants to maintain her femininity. The team goes through with the haircut regardless.

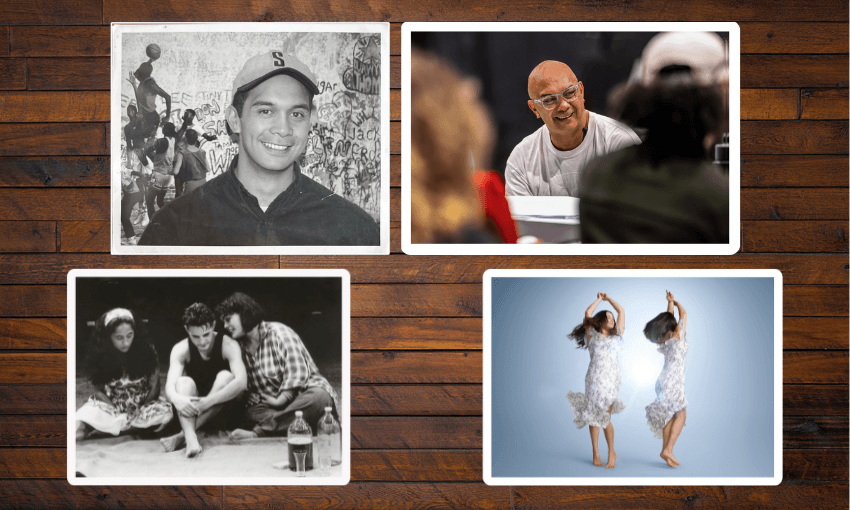

Six years later, I appeared as an African-New Zealander on a quite different reality show: Come Dine With Me NZ. It was a beautiful splash of all the variety of ethnicities across Aotearoa that are rarely given a spotlight elsewhere.

For me, it felt like a significant chance to represent my community with comedy, humour and curiosity, and hopefully inspire more people from my community to be seen.

However, the show became an unwitting replacement for the cancelled Campbell Live, facing a well-documented backlash. Facebook was full of comments calling the programme “a cultural freak show”. This, in addition to the ongoing TV3 boycott, meant that the comedy and joy I hoped to share was overshadowed.

I had another interesting experience the year before, appearing in a local film that required background talent to play an African-American dance crew. Because of my connection to the community, I gathered a group together, despite some having concerns the film would be culturally appropriating African-American dance and music. When the film was released, the outcome was disappointing – you could see our dance crew for literally one second.

Examples of African-New Zealanders on screen remain sparse. Shortland Street saw Zimbabwean actor Brian Manthenga appear as Dr Xavier Moyo in 2009, and Kenyan-Sudanese actress Karima Madut appears as Clementine in 2014. In the 2020 season of The Bachelorette NZ, Lesina Nakhid-Schuster was announced as the lead, before being awkwardly paired with another woman of European descent. This is nothing new for the franchise – The Bachelor US is notorious for having diversity issues.

There have also been times when local television has been more openly hostile towards people of African descent. In 2016, the Real Housewives of Auckland erupted when Michelle Blanchard was referred to by a racial slur. The very same year, Paul Henry defended the naming of the former N***** Hill. He said he resented the name change and expressed his desire to say the racial slur under the guise of freedom of speech. It was an unfortunate experience to be an African-American watching this live.

Hollywood has historically romanticised rhetoric from a very dark period in the American south, which has had an effect on New Zealand culture. From New Zealand’s own KKK headlines to a Confederate flag that flew at Rotorua’s stockcar track until very recently, the influence is evident. I once encountered a home in Hobsonville filled with 1900s minstrel show blackface statues, a reminder that there are many parts of our past we still need to remedy today.

In America, we see how corporate entities can co-opt on-trend social movements, sometimes for their own financial gain. Diversity and inclusion metrics can form a part of gaining government grants or additional funding for many top companies. On the surface, they appear ethical, but they can also be disingenuous. We saw this performative activism most recently at the 2021 Emmy Awards, where no non-Caucasian people won in any category across the board, which had the event dubbed a #whiteout.

Whether it is overseas or here in Aotearoa, offering a bone here and there for diversity is just not good enough without any real change or consistency. Another example is the release of Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings – Marvel’s first superhero film with an Asian lead – being referred to as an “experiment”. That sort of language and division keeps pockets of society in a perpetual state of fighting to be seen.

As an actor, we make a living off these differences. We desire true change that’s not divisive, and we know there is enough light for everyone to shine. Watching Merata: How Mum Decolonised The Screen brought home to me that there is still work to be done to diversify our film and television to reflect the many who live in Aotearoa. Our young people from all ethnic groups need to see that same diversity on screen – and not just in the background artists.

Still, we are always getting better. I felt proud for our Pasifika community when I see the success of The Panthers, a story the country desperately needs to see. I felt proud to represent my community on Come Dine With Me NZ, even in the face of public backlash. And I felt proud of Ajoh Chol, wherever she may be, and anyone else who unknowingly was the first of anything.