Mentalist, illusionist and performing magician Scott Silven says that he cares about storytelling and connecting to audiences. The thing is, it kind of works – even if you’re a jaded, panicked, uninspired journalist.

It is 9:30 am in the morning and Scott Silven has just asked me to think of a piece of art or media that inspires me. Unfortunately, my mind is completely blank. No thoughts, head empty. It’s a high stakes question, because he wants to read my mind.

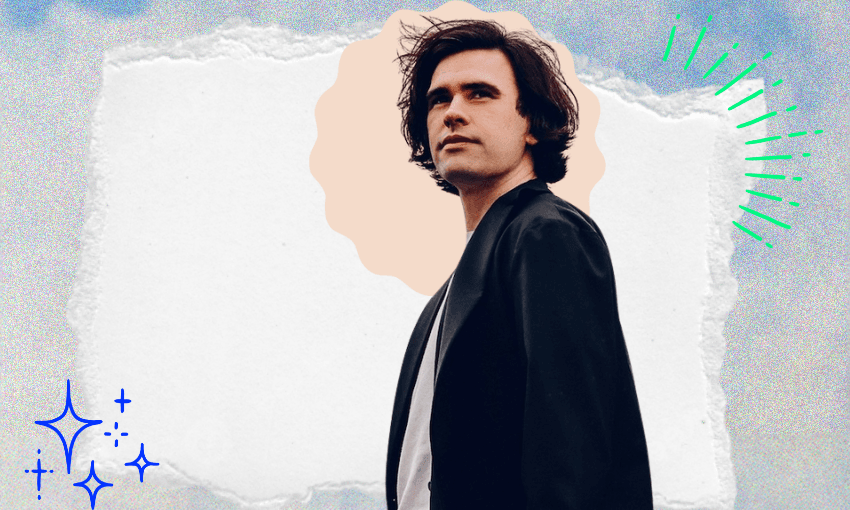

The renowned mentalist, here for the Auckland Arts Festival, is dressed entirely in black: chunky loafers, a v-neck shirt with an unsubtle Prada decal, a textured jacket. He arrived in Aotearoa last night and doesn’t seem even remotely jet lagged. I prepared for this interview last night but I didn’t know I was supposed to be inspired.

“Perhaps it’s a piece of music?” he suggests. Does my face look panicked? Is this how he reads minds, because he is good at interpreting people’s faces? Piece of music, piece of music – Beethoven? But I can’t remember the name of the song he dedicated to his blind student… suddenly the flotsam of my brain turns up the band A-ha; I read an article about the Norwegian band yesterday, because their lead singer Morten Harket has been involved in the push for electric cars in Norway. Out of the hundreds of works of art I’ve consumed, I guess I’m going to go with this one.

I don’t have time to think about it, because Silven is getting me to Google the release date of the song (‘Take On Me’) on my phone so I can keep it fixed in my mind during the interview. At the end, he’s going to try to guess what I’m thinking of.

Silven calls himself a mentalist. “Traditional magic involves putting people in boxes and strange things happening on stage, my work doesn’t involve any of that – instead of tricking people’s eyes, I work with people’s minds.” To the general public, these distinctions between branches of magic performance are innocuous: in essence, it just means that these are not flashy, leaping through fire, women in shiny dresses being cut in half kinds of tricks, but something more subtle. “There’s no smoke and mirrors in Wonders,” Silven says, referring to his show that is on until the end of the week as part of the Auckland Arts Festival. He laughs. “Well, there is quite a lot of smoke.”

This is definitely easy to prove: a few days later at Skycity Theatre, where Wonders is being performed, the room is filled with blue-tinged smoke. Silven walks in from the audience, speaking quickly in his smooth, soft Scottish accent. The set is theoretically based on his grandparents’ attic, his childhood secret place, where he would spend hours looking at the mountains out the window, waiting for it to get dark. Mountains, stars and the moon are a recurring motif in the show: at times the audience is invited to close their eyes and think of moments in their childhood. “I wanted to share the story of my childhood in Scotland and then mirror that with the audience’s experience,” Silven says, snapping his fingers – a move he deploys throughout both our conversation at my workplace and his stage show.

Watching the show, I’m not entirely convinced about the narrative. The story is vague, filled with evocative objects (an hourglass, a dictionary, a necklace) but devoid of personal details. I can’t read minds so throughout the show some of my wondering is personal: what did it really feel like to be a child in Scotland who was obsessed with magic? How does it feel to be an adult now, performing to thousands of people?

Magicians don’t reveal their secrets, though: what I am convinced of is that Silven works very hard. “I do four or five hundred shows a year,” he says. “I don’t really like the showmanship – standing on the stage speaking about how amazing the things I’m doing are is my least favourite part. But I like getting the audience to come with me.” He’s been performing wonders since before the pandemic, as well as another show that features magic tricks and a three course meal, with a smaller audience.

If he ever goes to a show with interactivity himself, Silven will be slouching his shoulders in the back of the room, trying not to make eye contact. “I really hate interactivity in shows!” He says – he’s more inspired by film artists, like David Lynch and Alfred Hitchcock. He’s perceptive enough to pick up on when an audience member doesn’t want to be called on, and no-one he beckons on stage looks grumpy or reluctant – nor do they seem planted, thanks to the random methods he uses to select people, like getting people to throw balls. “I’m a huge sceptic, but the hope is that when you get into the flow of the show, it’s about this collective journey.”

There’s definitely something to this: because so many audience members are part of the show, and everyone has a task to do, whether it’s distributing shreds of paper or collecting drawings, I definitely felt more connected to my fellow audience members than I do at most theatre productions, even if it was just through a sheepish smile to the woman next to me as she passed me a card with an inspiring word written on it.

But maybe this is beside the point: does the mentalism actually work? While not as flashy as other magic shows, people come to a mentalism performance to be amazed. Without excessive spoilers, perhaps the most delightful moment of the performance I watch is when Silven tries to guess a word in the mind of a teenage volunteer. At this point in the show, there’s something of a rhythm: audience member thinks of something, Silven writes it down and calls it out.

But this time, he gets it wrong – or does he? The trick is slightly more complicated than just a word on a piece of paper. The audience member does the whole jaw-dropped, hand-clapped-over-mouth thing when the word she was thinking of is revealed, and it’s difficult to resist that excitement. Even Silven looks gleeful. “People often say I get very excited on stage but when things work, I’m so thrilled that the audience made it work.”

He admits that “the story I’m telling on stage and everything you see might not be entirely true.” Silven appreciates that magic is something that has always drawn people in, and cites the recent increase in astrology and tarot as proof that people are drawn to mystery and the inexplicable. “In the skills that I do, I know the secrets of psychics,” he says.

Despite spending years of my life voraciously gulping down fantasy novels, I think I’m a sceptic too, but I know that Silven’s abilities don’t just work when he has the smoke and spotlights of the theatre. At the end of our conversation, Silven asks me to look deep into his eyes, and focus on the song I chose, my palms resting on his.

I suddenly feel worried: what if this world renowned magician gets it wrong, with my recorder on and everything? I don’t believe that he can really look into my mind, but how could he guess a song I picked at random on a Friday morning? “Does the piece of music have … it has three words, doesn’t it?” he says gleefully. “I’m just going to go through the letters of the alphabet here.” It’s strangely intimate staring into the eyes of a stranger, wanting and not wanting him to guess what I’m thinking about.

I’m trying to focus on the words of ‘Take On Me’ (there’s not that much to them after all) but simultaneously panicking: what will I do when he gets to the letter T? Do I want to somehow give him a clue? In my stress, certain my hands are sweating, my fingers twitch when Silven gets to Q.

I have no idea what my eyes do, but somehow Silven is onto it. “It’s a T, isn’t it!” he crows, grinning. “I’m thinking this is synth – it’s ‘Take On Me’ by a-ha! I love that song, it’s still such a banger.” In the recording, my voice is slower, confused but happy. “Yes, that’s amazing,” I say.

“You come to a theatre and you know it’s artifice, and you know it’s not real, but it’s an experience – it’s about how it makes you feel,” Silven says. Part of why hypnosis and mentalism work is that the audience wants to see it work: I’m sure I participated in this in some way, but I am nonetheless completely impressed. Afterwards I search through the transcript of our interview in case I said “take on me” as a Freudian slip, but I didn’t.

Just by talking to Silven and going to his show, I found myself a little more willing than usual to be amazed. It doesn’t really matter what’s real, or how it’s done: preparing yourself to be delighted is its own kind of magic.

Wonders is showing until Sunday, March 24 at Skycity Theatre