Metroidvanias are some of the most notoriously difficult, directionless games in existence, but for Jesse Dekel, they were a rock during a rough time at sea.

The very first Game Boy Advance I destroyed was one of those clear-blue ones. I smacked my 8-year-old head into the thin-film-transistor liquid-crystal display screen with the force of what I imagine was probably at least a thousand angry suns. What I left was some Rorschach ink blotch looking thing found in the DSM-IV, likely indicative of a latent personality disorder. I smelled battery acid, and immediately started crying. I spent the next year trying to save NZD$150 to pay my parents’ friend back, because it belonged to her, because of commodity fetishism, and because Marcel Mauss wrote a book about how exchange works.

The game I was playing was Sonic Advance 3, and it sucked. I was waiting for my parents in my dad’s car, because we were headed to some hippie crafts fair thing, but they left on foot without telling me, so I just self-isolated, and voiced my frustrations on the screen of my friend’s beloved handheld system.

The second Game Boy Advance I had, I didn’t destroy, but it definitely got nicked by some absolute scoundrel at high school. It was a blue Game Boy Advance SP, the version with the shittier backlight. I would sit in the corner of my English or Geography class playing Final Fantasy Tactics Advance, while self-isolating myself from whatever drivel my teachers had to say about how wind turbines will singlehandedly solve global warming, or some neoliberal hot take on the Tauranga tourist industry.

It was way easier to separate myself from my environment and immediate surroundings by staring at the very cool fantasy pixel art depicting the land of Ivalice, and jamming sombre tunes that banged way harder than they had any right to.

The last Game Boy Advance I broke was an onyx Game Boy Advance SP, with the dope backlight feature. It miraculously escaped from my backpack that I was putting down, and with the inertia of the dismount, nosedived, and smashed against hardwood floor. I paced around defeatedly picking up the morsels of plastic pieces, and then attempted to tape back together, in what I hoped would turn out like kintsugi, or at least work.

At the time that this dramatic destruction happened, I was living in the San Francisco Bay Area. By ‘living in’, I mean that I was staying at a homeless youth shelter, having been homeless for two months, and illegal. The shelter was incredibly punitive, with shitty, transphobic, inept staff who were just trying to get their $15 an hour, and dip. It was heavily regulated, so much so that every client had to be in by 7pm, and out no earlier than 8am, or risk losing their bed.

The first day I got there, I was walked through a ridiculously arduous intake process, in which I had to sign a bunch of contracts agreeing to bizarre rules, successfully punishing us for being homeless.

Seeing as though I was sharing a room with 40 other homeless people, and had to be there at least 13 hours a day, all I had to do was either read while ignoring the screaming and frequent fights going on around me, or isolate myself in a corner and play on my Game Boy.

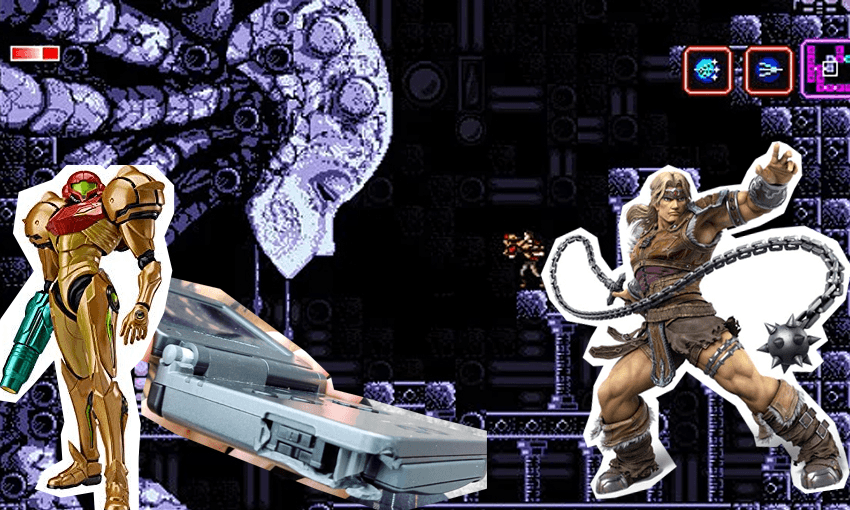

It was so ridiculously boring, as though having something to do was a luxury of the housed. So I created my own little alcove of solitude to combat the sheer boredom of it all, scored a bootleg 24-in-1 GBA multicart off of eBay, and then played the fuck out of Castlevania for hours.

I started off with Harmony of Dissonance, and was really just trying to find solace in the guaranteed progress that comes included in every Metroidvania game. These are platforming games defined by their use of ‘guided non-linearity’, and ‘utility-based exploration’. Often interconnecting with the game’s heavy focus on backtracking, and coinciding progressively revealed minimap. It’s debatable whether this prescription entails the game being strictly 2D, or even a platformer in some cases, and a lot of boring people get really passionate about this discrepancy.

These games are popular because they bank on instilling an emotional satisfaction in exploration, and the progress earned in beating difficult bosses. They reward players for playing the game, in such a direct way. This emotional impact is not unique to Metroidvanias, but is definitely a strong feature in them, and probably why some people call Dark Souls a Metroidvania. Metroidvanias are the Dark Souls of reductive comparisons.

Compared to getting rejected five times a day from whatever retail or hospitality job I foolishly applied for, it was a fucking blast to be able to successfully beat generic-named bosses like ‘Giant Bat’, or ‘Peeping Big’ (???). Every time I passed by a gothic-themed blocked path, I knew that in 30 minutes I’ll have found some predictable way to get through it.

While at the same time I had to use Excel spreadsheets-level planning to tactically determine the best time to use the women’s bathroom without getting screamed at. I could grind Juste Belmont’s goofy ass if I wasn’t a high enough level to slay a minotaur, but I couldn’t beat up a bunch of sentient suits of armour and then be able to defeat a Starbucks employer, or even the dude who called me a faggot and followed me for a minute. A million arduous articles have been written about the harms of ‘escapism’ in video games, but my friends were finding the same relief in meth and benzos, so fuck it.

The reason I enjoy these games is maybe partly due to this backtracking concept, and the progressive familiarity earned by small wins. I also probably have a deep-seated need for isolation that playing handheld games satiates. This is especially the case when applying a gothic loner theme that in turn shapes over-world exploration and intrigue. Incidentally, Metroidvanias are the perfect choice to play amongst a backdrop of solipsistic self-loathing. Not because of the difficulty entailed in them, but because of the built-in satisfaction and weird mix of familiarity and adventure. In any case, the solitude these games have helped me with aren’t exactly unique to my playing of Metroidvanias, but they definitely fit in with the shtick.

Castlevania’s guided nonlinearity gives off a false sense of an open world. The player starts off by exploring, and subsequently discovering neat things about the gothic, Monster Mash landscape until an inaccessible area or item catches their eye. This allusion helps guide the player along, and employs a feeling of yearning to become more powerful. The player wants to get stronger to overcome a challenge, and when they finally do so, the player gets rewarded with new areas, new enemies, and more locked away secrets. When I’m walking around the city all day, trying to hustle enough to warrant a taco, it feels more like unguided linearity.

This experience resonated with the insurmountable homeless resources available, that are really just not accessible to anyone that needs them, and ultimately don’t achieve shit. Being bounced around and around to various outreach centres, drop-ins, community buildings etc gets really repetitive, and unsatisfactory. Nothing is achieved. I become Dracula. In Castlevania nomenclature, the ‘guided’ part was lost on me. I couldn’t get access to the utilities, and general RPG-style power-ups needed to get through gates.

Near the end of Circle of the Moon, I was having trouble overcoming the spontaneous difficulty spike and couldn’t beat Dracula’s Final Form™, so ended up grinding Liliths in the Underground Warehouse for hours. It was the kind of repetition induced in my ongoing job interview, and resume drop-offs, which put me in a glassy, somatic state that allowed me to tune out and lethargically hope for the best.

I think this attempt to reach some sort of relaxed state and find enjoyment in isolation is how I’ve used Game Boy Advances. To me, they offer a private, secluded entertainment that allows for an escape from my surroundings and problems. The sense of familiarity with these surroundings also gave me a way to understand how I was emotionally responding to things, and project my experiences onto something trivial, and inconsequential, like how to obtain a better luck stat in order to get the armour that has the best defence stat possible.