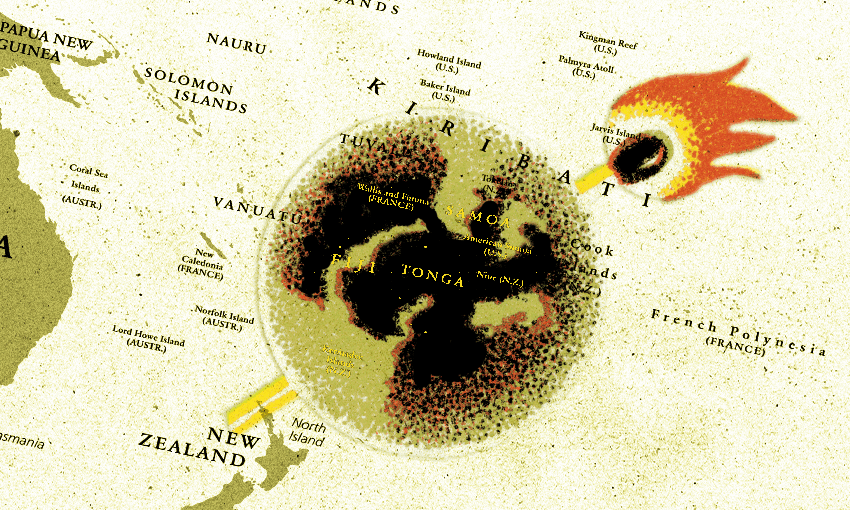

Over the course of the Cop28 conference, our Pacific neighbours have been some of the most vocal critics of the new government’s reversal of the oil and gas ban.

It’s right there in the Act and National coalition agreement: the government will “repeal the ban on oil and gas exploration”. The ink on the deal had barely dried when the Cop28 climate conference in Dubai started – just in time for new climate change minister Simon Watts to be asked whether the policy reversal would cause any issues with international partners. He insisted that it would not.

New Zealand’s Pacific neighbours, whose low-lying islands are among those most vulnerable to rising seas, are paying attention to the new government’s policy. Palau’s president Whipps Junior has described it as a “backwards move”, telling RNZ that “New Zealand as a Pacific Island… should take a leadership role and should be active in doing all they can to transition away from fossil fuels. They shouldn’t be going out and exploring more gas and oil.”

For Pacific activists, watching the New Zealand government’s reversal has been frustrating. “For New Zealand to backtrack on this spells climate disasters of unimaginable proportions for our Pacific climate frontline communities, and elsewhere across the world,” said activist Lavetanalagi Seru in November. Seru, the regional coordinator of the Pacific Islands Climate Action Network, was reacting to remarks from Gerry Brownlee that gas was a good transition fuel.

Vanuatu’s climate change minister Ralph Regenvanu has been similarly scathing. “We call on [the National-led NZ government] not to do it. To be in line with Paris, the 1.5 degree target, the science says you cannot do new fossil fuels,” he told Newsroom at the Pacific Islands Forum in November.

New Zealand is part of the Pacific, and a member of the Pacific Islands Forum; the government signed up to a PIF commitment to transition away from fossil fuels in the Pacific last month. What happens in the Pacific has a direct impact on New Zealand, including on migration. As Covid showed, parts of the New Zealand economy are completely dependent on Pacific labour. Researchers have said the New Zealand government must improve its system for climate-related migration, which is already happening.

Meanwhile, Tuvalu, which is one of the lowest-lying countries in the world, has pledged to become a “digital nation”, creating a clone of itself so that it can still exist as a country when it has no land. It’s using this as a way to influence people around the world to take climate action; the digital nation includes a new definition of statehood that means it continues to exist even if it has no land and a 3D scan of the nation’s many islands as proof of its territory. It’s both a serious enterprise, an attempt to leverage other digital trends (the .tv domain name is a key source of revenue for the country, and the project will include blockchain technology) and a bold statement.

“While we look to grow our international alliances, we want to remind nations of our Tuvaluan values of kaitasi (shared responsibility) and fale-pili (being a good neighbour),” Kofe said, in a written response to The Spinoff. “Without global commitment to our shared wellbeing, and reducing the impacts of climate change, the fate of our homeland is in the hands of the world.” With its land under threat, Tuvalu also signed a treaty with Australia last month that offers visas and funding for climate adaptation – but in return gives Australia a degree of control over Tuvalu’s foreign policy, which has been described by Pacific academics as a form of colonisation.

In March this year, six Pacific nations signed the Port Vila call for a Fossil Fuel Free Pacific, agreeing to phase out fossil fuels as soon as possible in the wake of increasingly damaging cyclones caused by fossil fuels. These countries, Tonga, Fiji, Niue, Solomon Islands, Tuvalu and Vanuatu, agreed to join the Beyond Oil and Gas Alliance, which New Zealand also joined because the government had said it would stop issuing oil and gas permits. (New Zealand is only an associate member, as the government was still issuing shorter-term exemptions to the ban, even before the National government took over.)

At the start of 2022, New Zealand had 59 million barrels of crude oil and 1,967 petajoules of natural gas (one petajoule equals 278 million kilowatt hours of electricity) remaining in our known fossil fuel reserves. By comparison, the UAE is one of the world’s top oil producers and has estimated reserves of more than 100 billion barrels, producing about three million barrels a day. New Zealand’s oil supply is tiny in the global scheme of things, but it also has a disproportionate impact, according to a new report from Oxfam’s climate justice team.

“It matters to end the production of fossil fuels, and not just consumption,” says Nick Henry, the lead author of the report. The momentum of new oil and gas fields is chiefly financial, and therefore hard to stop – part of why the original ban by the Labour government was of future exploration, not for oil and gas already in production. “When those investment decisions are made, it means the emissions will be produced.”

The impact is also disproportionate because of New Zealand’s previously held role as a leader among wealthy nations in reducing fossil fuel consumption. “New Zealand has a diverse economy and the capacity to transition away from fossil fuels,” Henry says. “The political leadership New Zealand has shown until recently, joining Beyond Oil and Gas talks at the Cop summits and standing alongside the Pacific – it’s embarrassing for New Zealand to walk away from the commitment, and it will harm our international reputation.”

Henry reels off a list of some of the ways that the climate crisis is already affecting Pacific communities – not in the future, but right now. “Pacific communities have experienced the worst of the climate crisis for years – worsening weather, regular emergency-level cyclones, all the effects on crops from sea level rise and the salination of the soil, changing rainfall, [the effects] on coral reefs and fishing grounds, which are in serious trouble.”

Pacific Islands have much lower per-capita emissions than New Zealand, but are experiencing the effects of climate change more severely. Henry argues that while New Zealand’s current rate of declining fossil fuel production – in part thanks to the moratorium on new exploration licences – puts us on track for Paris Agreement targets, a fair response to the climate crisis would mean reducing fossil fuel use much faster. As Cop28 draws to a close, Henry warns against “weasel words” like “unabated” or “phase down” that inject uncertainty into climate agreements, often at the behest of oil-producing countries. Regardless of what the New Zealand government does now, “we’re out of time for fossil fuels, anywhere in the world,” he says.

Activist Seru is clear. “We need to see that New Zealand, under its new government, will stand with the Pacific – not with the fossil fuel industry,” he said.