Marine ecologist Benn Hanns has spent more than 10 years sticking his head under the water in the Hauraki Gulf to monitor the effects of marine reserves, and let him tell you – they’ve got benefits.

When I first started quantifying marine life in the Hauraki Gulf, I was a third younger than I am now. There were no grey hairs, and somehow I had a six pack without ever going to the gym. Times have changed. It was back then (the peak of my youth) that the Hauraki Gulf / Tīkapa Moana Marine Protection Bill, which is currently before parliament, was starting to take shape among scientists, iwi and other stakeholders.

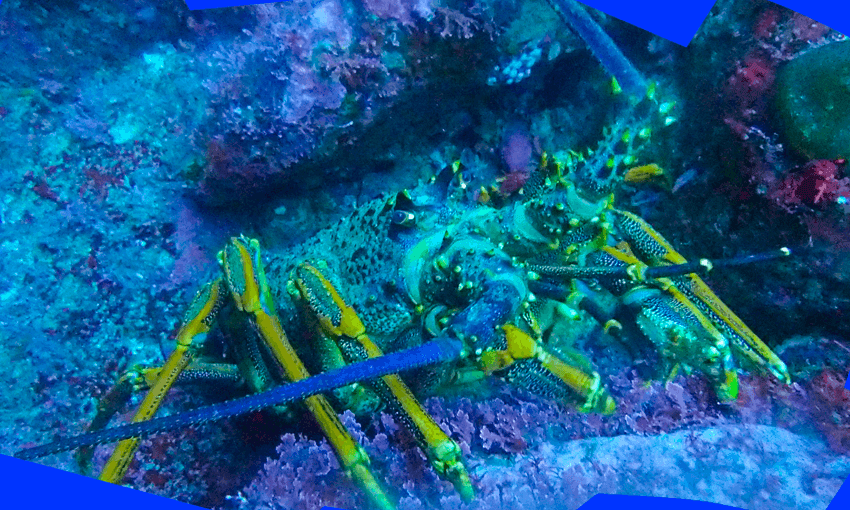

Right now, only 0.3% of the Hauraki Gulf Marine Park is fully protected across six marine reserves. Even though they are relatively tiny, their impacts have been massive. Populations of important species have rebuilt, and ecosystems have been restored. In the older reserves like Goat Island (officially called Cape Rodney to Okarari Point Marine Reserve), reef predator populations such as tāmure (snapper) and kōura (crayfish) have recovered. These predators have suppressed kina numbers and the impact of kina grazing which in turn has allowed kelp forests to flourish.

Marine reserves are not surrounded by fences and their effects are not limited to their boundaries. The Goat Island marine reserve, which is only about 5km2, has been estimated to contribute up to 11% of newly settled juvenile tāmure to the surrounding 400 km2. This is because marine reserves allow animals to get big and big animals produce more eggs – it takes 36 30cm-long tāmure to make the same amount of eggs as one that is 70cm long. In essence, the reserve has acted as a baby snapper factory, supplementing tāmure populations in surrounding areas.

The protections proposed in the Hauraki Gulf / Tīkapa Moana Marine Protection Bill would protect about 6% of the Gulf by extending two existing marine reserves and creating 12 new high protection areas. It would also introduce five new seafloor protection areas. The main difference between marine reserves and high protection areas (HPAs) is that while the former are “no take”, the latter allow for customary fishing. Their placements of the proposed HPAs have been designed using key principles on size and location to create a network of effective protection around valuable ecosystems and key species.

For the most part, the proposed protections have been warmly welcomed. People are well aware that the Hauraki Gulf is facing ecological problems and is under pressure from fishing, contamination from surrounding land use and climate change. But, there has been some pushback from recreational fishing groups such as Legasea, and interesting rhetoric from our new minister for oceans and fisheries Shane Jones, who is often aligned with the interests of commercial fishing. It’s a good time, then, for a reminder and deeper dive into the potential benefits the bill promises.

Like the nerd my work allows me to be, I’ve spent a bit of time calculating the potential benefits of the proposed protections. My research has mainly focused on crayfish and snapper, because they are key species in the gulf and have been heavily impacted by fishing. A few weeks ago I published research in the Gulf Journal, where you can find more detail on the following.

My calculations indicated the proposed HPAs have the potential to dramatically increase the biomass (literally the mass of living animals) and egg production of tāmure and kōura in the Gulf. I estimated that the biomass of reef-associated tāmure in the Hauraki Gulf could increase by 3.5 times and overall egg production could increase by 3.8 times. For kōura, the spawning biomass (the combined weight of all sexually mature females) could increase by 3.8 times and annual egg production by 3.3 times. These are dramatic increases considering the proposal aims to only protect 6% of the Hauraki Gulf Marine Park.

The animation below shows how you’d expect the larvae to move beyond the protected areas over 10 days. Exisiting marine reserves are in purple, while the proposed HPAs are in red. This preliminary analysis uses a hydro-dynamic model which takes into consideration the movement of the water in the Gulf alongside the biology and size of tāmure eggs. I also plan to make a similar model for kōura, so watch this space.

Protecting specific areas, rather than species specific regulations on fishing is important in the Hauraki Gulf. The gulf is unique because it’s an area where recreational fishing is equally, if not more, impactful than commercial fishing. Recreational fishing has fewer limitations and is harder to manage. The beauty of protecting areas is you protect a whole ecosystem. It’s a multi-species holistic protection, which would be hard and time-consuming to achieve with regulations like size limits and catch limits.

The conversation around marine protected areas is too often about fishing. These areas are about so much more. They’re not even just about being able to study things (we’ve already got plenty of material). They’re about preserving. People can go snorkelling there and see a healthy ecosystem, because it still exists. They’re also about resilience – climate change will bring new pressures and protected ecosystems will be stronger to be able to cope.

When I am three times as old as I am now, there will be too many grey hairs to count. If the bill passes, fish in the gulf will multiply in the same way.