As the evidence of ketamine’s positive impact on depression and other mental illnesses grows, Naomi Arnold talks to Holly*, a Dunedin artist and anxiety sufferer whose prescription for the drug has made a huge difference in her life.

For more than 30 years, Holly’s chronic anxiety has been attacking her body. When the panic comes on she gets very sweaty, her stomach churns, her jaw clenches, her shoulders scrunch up, and her heart thumps in her chest, so hard she can’t escape it.

“It’s panic stations: you’re in danger, this is frightening,” she says. She would try to rationalise the symptoms away and tell her brain that it was “just anxiety”, but they didn’t stop. Along with her other diagnoses of depression and PTSD, her anxiety was so detrimental that her life was “stagnating”. The unbearable symptoms had completely controlled the 44-year-old for most of her life.

That was until she joined a University of Otago study into the effects of ketamine on anxiety and started taking it twice a week. She found the effects immediate and almost magical; her brain unclenched and she had the space to think and process what was going on inside her. It worked from her first low dose, separating her from the fire raging in her body. Two years on from the study, she still takes ketamine twice a week on prescription and is able to live a mostly normal life.

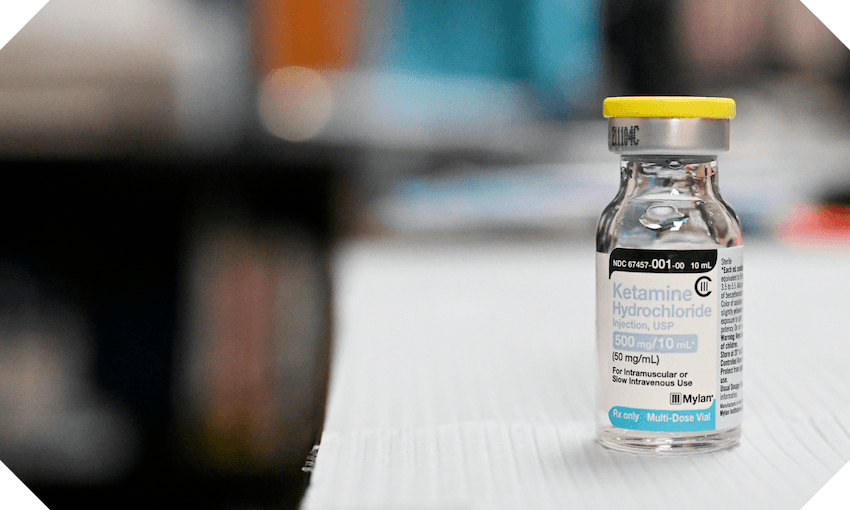

Evidence has been accumulating for years on ketamine’s positive impact on depression and other mental illnesses. On Friday last week, an Australian and New Zealand double-blind randomised controlled trial was published in the British Journal of Psychiatry, finding that a low-cost version of ketamine was effective for treating severe, treatment-resistant depression when compared to a placebo.

In their paper, the researchers found that more than one in five people achieved total remission from their symptoms after a month of twice-weekly injections, while a third had their symptoms improve by at least 50%. In Australia, the researchers are now applying to the government to fund the treatment because it’s so powerful and so cheap – the generic ketamine can cost as little as A$5 a dose.

Holly was part of an earlier study run by one of the new paper’s researchers, Paul Glue, a professor of psychological medicine at the University of Otago. In a media briefing last Friday, he said Douglas Pharmaceuticals in New Zealand is one company that is already “fairly advanced” in developing a slow-release ketamine tablet that can be taken easily and safely at home with few side effects, though it still has trials to complete and regulations to pass.

“That may be where ketamine treatment goes, at least in one iteration, in the next few years.”

He adds there’s “huge opportunity” for treatment in New Zealand, with ketamine working “beautifully” for generalised anxiety, PTSD, and specific phobias such as spiders.

“It may be an underlying brain process that makes one prone to depression and anxiety, and ketamine’s getting rid of that process.”

He says there’s currently one private clinic in New Zealand providing ketamine treatment, along with two universities. Appropriate training would be needed for clinicians before it is available in New Zealand, he says, which we are currently lacking.

“There would be reluctance to just jump in and try it.”

But he does see a future where it is more widely available in hospitals.

“In New Zealand we have a slightly less adventurous government in terms of making access to psychedelics easier,” he says. In order for it to become a treatment, the Misuse of Drugs Act would need to be revoked, among other legislative and health system changes. Implementing it would then require further training and more experienced clinicians.

Ketamine is most popularly known as a recreational drug. The New Zealand Drug Foundation’s drug information website The Level describes recreational effects ranging from the pleasant (relaxation, euphoric, pain relieving) to decidedly dangerous (seizures, loss of consciousness, problems breathing, psychosis).

Large doses can lead to what’s known as a “k-hole”, where you can’t move or speak. Long-term use can cause severe bladder damage, liver failure and kidney failure as well as memory loss and other mental effects.

But under medical supervision, it’s helped Holly. Twice a week, she syringes the contents of an ampoule into a glass of orange juice and sips it slowly. She has to drink it over about two hours to avoid “weird psychoactive stuff”, which has included heart racing, paranoia, and an incident where she really did drink it too quickly and some Dungeons & Dragons characters in a podcast she was listening to started talking to her.

“It’s a very, very intense drug,” she says. “It’s very full-on. [I was] taught how to take it in the right manner through the trial. I don’t think it should be available to just anyone.”

She’s noticed its impact at a daily level as well as in more stressful situations. Recently, she took a trip to Australia and had “a nightmare” in Melbourne that would have once caused her a huge amount of distress; travelling is typically a big trigger for her anxiety and panic.

“I picked up the wrong bag on the SkyBus,” she says. “But I’d taken some ketamine the night before and so I was able to navigate that whole drama without having a total meltdown. My heart was pumping quite a bit, but it wasn’t overwhelming. And I could still think relatively clearly.

“Ketamine gives me the chance to intellectualise what’s happening in my body and think my way out of it. I can’t normally do that.”

In fact, the ketamine gave her such confidence that she’s now studying at the University of Otago, after 20 years of working in the disability sector. In her first semester, she got straight As. Being a mature student would have been too overwhelming before – now, she finds herself giving advice to her classmates, 25 years younger, on how to navigate the mental health system. She’s hoping to get a job in government or policy when she graduates.

What has also helped a lot is her regular appointment with a trauma psychologist.

“I don’t think the ketamine on its own would be as helpful,” she says. “My psychologist gives me all sorts of mental tools to be able to cope with what’s going on. She’s incredible, she changed my life as well. But I would get to a certain point and then the body would just take over.”

Holly had tried the usual round of treatments for her illnesses before she joined the study. Getting her trauma therapy took more than 10 years of a progressively worse health spiral until she was in such “drastic circumstances” that she could access the therapy via ACC sensitive claims funding.

“It’s been a really long journey, and I basically tried to do it all on my own. And it didn’t work,” she says. “You’ve got to keep fighting and it’s so hard, and so exhausting.”

Now, coupled with the therapy, the ketamine has resolved Holly’s anxiety, depression and PTSD symptoms to such an extent that after decades of struggle she’s finally managed that simple yet elusive outcome in mental health care – her treatments have lined up, they’re working pretty well, and she feels mostly free to live her life as normal. Any symptoms she does have, she can manage without meltdown.

“[Ketamine] just gives me breathing room,” she says. “It stops that energy siphon that happens when you’re super anxious that just sucks away life and energy. It helps me feel calmer and happier and like I can function in society without dread.

Before, she couldn’t go out much – the people would be too much.

“It’s helped me become a little bit braver,” she says. “I’ve also grown a lot mentally because I’ve had the physical space. I have had that respite from the anxiety symptoms. It’s helped the [therapy] work I’m doing in my head to carry on, so I can progress in life. To have a whole lot more control over that is just life-changing.”

* The Spinoff is withholding Holly’s last name to protect her privacy.

This article interviews one person about their experience with a medical ketamine study and does not purport to offer medical advice. Please consult your doctor about your own specific health situation.

Ketamine is classified as a Class C drug under the Misuse of Drugs Act. Possessing ketamine, buying it, selling it, making it, importing it, or giving it to others is against the law. Information on ketamine and its effects can be found at The Level.