Before we can Indigenise science, we have to decolonise science, and the pūtaiao model provides a pathway.

We are witnessing a resurgence of Indigenous knowledge and growing acknowledgement of its scientific value worldwide.

In Aotearoa, there’s been some progress, including the introduction of a public holiday to mark Matariki, the beginning of a new year in maramataka, the Māori calendar based on the phases of the Moon, the movement of stars and the timing of ecological changes.

But progress has not been straightforward, with some scientists publicly questioning the scientific value of mātauranga.

At the same time, Māori scientists have drawn on and advanced mātauranga and continue to make space for te reo, tikanga and honouring Te Tiriti o Waitangi in research.

Our recent publication explores pūtaiao – a way of conducting research grounded in kaupapa Māori.

In education, pūtaiao is often simplified to mean science taught in Māori-medium schools that includes mātauranga, or science taught in te reo more broadly. But science based on kaupapa Māori is generally by Māori, for Māori and with Māori.

Our research extends kaupapa Māori and the important work of pūtaiao in schools into tertiary scientific research. We envision pūtaiao as a way of doing science that is led by Māori and firmly positioned in te ao Māori (including mātauranga, te reo and tikanga).

Pūtaiao as decolonising science

Pūtaiao privileges Māori ways of knowing, being and doing. It is a political speaking back for the inclusion of te ao Māori – mātauranga, te reo, tikanga and Te Tiriti o Waitangi – in science.

Conducting research this way is not new. Many Māori scientists have drawn on mātauranga and kaupapa Māori in their research for decades. Our conceptualisation of pūtaiao is an affirmation of the work of Māori scientists and a pathway for redefining and transforming scientific research for future generations.

Decolonising science is at the heart of pūtaiao. It challenges and critiques the academy and disciplines of Western science. Decolonising science requires a focus on histories, structures and institutions that act as barriers to mātauranga, te reo and tikanga.

We argue that decolonising science is a necessary step before we can Indigenise science.

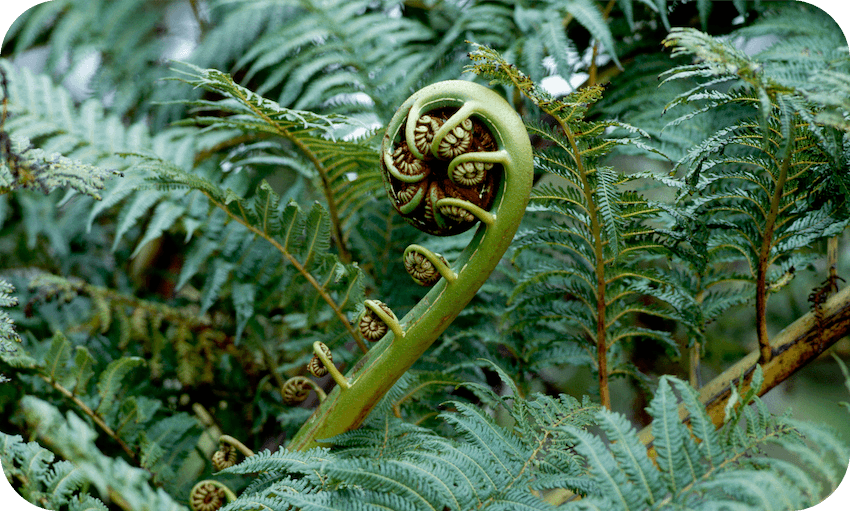

Like mātauranga, pūtaiao is embedded in place and in the people of those places. It centres, prioritises and affirms Māori identity in the context of scientific research and science identity.

The importance of the researcher in pūtaiao

How we identify as Māori – tangata whenua or rāwaho (people not related to the hapū or whānau), ahi kā (people who keep the home fires burning) or ahi mātaotao (people who may have been disconnected to the land through lack of occupation over generations) – fundamentally changes how we interact with people and place through research.

To practise pūtaiao effectively, researchers are required to understand who they are and how that informs the research questions asked, the research relationships formed, the location of the research and the way research is conducted.

Kaupapa Māori, as articulated by distinguished education scholar Graham Hingangaroa Smith, requires two approaches to decolonisation: structuralist and culturalist.

Culturalist approaches centre te reo, mātauranga and tikanga. The groundbreaking work led by professor of marine science and aquaculture Kura Paul-Burke, using mātauranga to enhance shellfish restoration, is an excellent example of a culturalist approach to decolonising science.

A structuralist approach means paying attention to and dismantling the structures within science which continue to exclude Māori knowledge and people. It encourages us to think about the colonial roots of science and how science has been used to justify colonial violence and oppression of Māori.

Captain Cook’s “scientific voyage” to Aotearoa is a great example of how colonisation occurred under the guise of science.

Challenging the status quo

Pūtaiao reframes the conversation around the inclusion of mātauranga Māori in science. It considers the relationship between te ao Māori, the researcher and science to imagine how to decolonise, Indigenise and transform science.

We understand science not simply as scientific knowledge but as a knowledge system that spans research, education, academia, scientific practice and publications, as well as the evaluation and funding and access to science, its legitimacy and its relationship to policy and government.

There has been much research on Māori experiences within the science system, including the cultural double shift when Māori scientist are expected to lift their colleagues’ understanding, racism and the difficulties of inclusion. A lone Māori scientist is often tasked with upskilling their colleagues, representing Māori on committees and leading cultural practices in addition to standard loads of supervising, teaching and research.

To challenge the status quo, we explored different ways of creating ecosystems or “flourishing forests” of Māori scientists to advance pūtaiao. This includes creating networks of Māori staff in science by establishing research centres such as Te Pūtahi o Pūtaiao and the Centre of Indigenous Science.

It also means creating research projects that move beyond the siloed disciplines within the science system. In this way, pūtaiao enables Māori to see themselves and be seen within science.

Pūtaiao offers a practical foundation, connecting Māori science leaders to transform science. Whether this happens through new university courses, academic programmes, research centres, institutions or regional and community hubs remains to be seen.

It is certain, however, that pūtaiao, conceptualised as kaupapa Māori science, offers many pathways for Māori scientists to continue to draw on and advance more than mātauranga to decolonise and, ultimately, redefine science into the future

Te Kahuratai Moko-Painting is co-director of the Centre for Pūtaiao, University of Auckland. Tara McAllister is a research fellow at Te Herenga Waka — Victoria University of Wellington

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence. Read the original article.