Disruptions to the global pharmaceutical supply chain aren’t just affecting menopausal people’s access to estrogen patches in Aotearoa – trans women are also having trouble accessing the ‘life-changing’ hormone replacement.

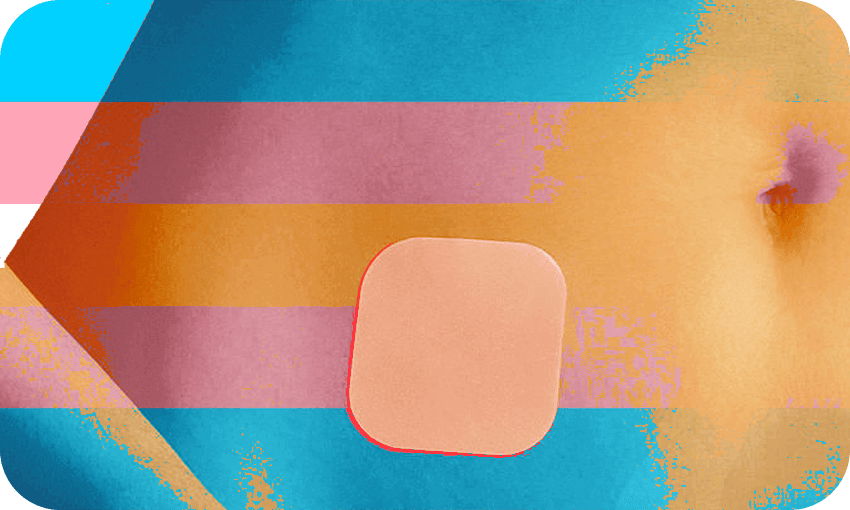

Ella Jenkins has had a steady supply of 100mcg “Estradot” patches for the last two and a half years. Sticking one estrogen patch twice a week on her body, the 23-year-old journalism student has felt she could be the person she was meant to be. A month ago, however, Jenkins couldn’t get her preferred medication because her pharmacy had run out amid a nationwide shortage, and instead was prescribed a new, oral course of hormone replacement therapy (HRT).

Unlike her twice-a-week dosage in patches, Jenkins is worried about remembering to take her one 2mg “Progynova” pill each day like she’s supposed to. She’s concerned about how her body will cope with the side effects of the pills, including changes in mood due to a potential hormone imbalance and the long-term impact on her liver. And she’s worried about shifting from a stable hormone regime that has been working for her, “to stabbing in the dark to try and find one that works similarly enough”.

Estradot, the pharmaceutical brand name for natural female sex hormone estradiol, is just one form of HRT that people use to control their estrogen levels. People experiencing menopause typically take HRT as short-term relief from hot flushes, mood swings and other symptoms by replacing the estrogen their ovaries would’ve made before their menstrual cycles started winding down. HRT is also available to trans men and women as part of their gender-affirming healthcare. Besides pills and patches, injections and gels or creams are other options for trans women to administer themselves estrogen.

Jenkins’ pharmacy isn’t the only one running short of Estradot – the scarcity is nationwide. Nor is it new, with several supply disruptions experienced since August 2020. Pharmac director of operations Lisa Williams says stock has arrived in Aotearoa and was released to wholesalers on July 19, so pharmacies should now have supply. Shortages of many HRT medicines have been reported in Australia and Europe as suppliers report “extraordinary” increases in demand as local and global distribution channels try to alleviate Covid disruptions.

Williams says there are no “known” supply issues for Progynova and Estrofem, another estrogen pill, and deliveries for a delayed shipment of progesterone, a secondary female sex hormone, have been scheduled for this month. Currently, Pharmac only funds Progynova and Estradot, and partially funds Estrofem. The agency is consulting on whether to fund progesterone, with a decision expected in late September. “As this is a global issue, we may experience ongoing disruptions with supply of HRT medicines,” Williams says. “Our team continues to talk with the supplier regularly and is continuing to monitor this situation.”

Dr Bryan Betty, the medical director of the Royal New Zealand College of General Practitioners, adds that Covid’s impact on pharmaceutical supplies is the “fundamental reason” for the widespread scarcity. “We need to remember that New Zealand sits at the bottom of the Pacific, a long way from where a lot of these medications are produced. It’s worse at the moment than we’ve seen previously.”

Much of the media coverage of the Estradot shortage to date has highlighted the experiences of menopausal people over the course of the pandemic. But trans women like Jenkins are coming up against the same headwinds. Jenkins is at the point in her transition where physical changes are “negligible”, although changes may be happening that she can’t see; a blood test in a month, for example, will indicate how high or low her testosterone levels are since using Progynova. How the stress of the change will impact her mind is not yet clear either. “That’s the big impact – is this going to work? How am I going to feel? That sort of anxiety of going into new medication.”

Betty, the medical director at the College of GPs, explains that side effects and other issues arising from changing medications are common, and working hard to achieve an equivalent dosage is important. Patches such as Estradot administer estrogen through the skin, whereas estrogen contained in pills like Progynova is processed by the liver and users need a higher dose of it. Oral estrogen is an acceptable alternative, “except we need to accept that often there is a bit of work in terms of getting the right dose or dose equivalency in a way that doesn’t run into any issues with side effects or unintended consequences,” he says.

Even before Jenkins noticed any physical differences after starting on Estradot, simply being able to see the patch on her body boosted her morale. “I knew things would change,” she says, adding she was impatient to notice her chest feeling firmer, her hair growing differently and her skin feeling softer. “I was told from the get-go that it’s not a miracle drug, it’s not going to make you perfectly feminine. But I was just desperate to start looking like the body that I felt like.” She sympathises with transgender people who have waited months to see an endocrinologist and be given the green light to proceed with HRT, only to encounter the country’s nationwide patches shortage.

Gender-affirming healthcare is top of mind for New Zealand’s transgender community. Trans support organisation Gender Minorities Aotearoa (GMA) runs the country’s largest support forum for trans people at 2,500 people, and much of the group’s discussions relate to healthcare, says GMA national director Ahi Wi-Hongi (Ngāpuhi, Ngāti Maniapoto). “A shortage usually gets talked about among the community pretty quickly.” People are worried that alternative estrogen treatments could run out too, but Wi-Hongi says running out of estrogen is not going to happen. “You’re going to be OK, you’re still going to be able to get the medication that you need, even though it is a hassle to have to change it.”

Jenkins is unsure how long she’ll be on oral pills – “that part really bugs me…there’s no timeframe. I could be on it for a year or two. I could be on it for a month. I don’t know”. She hopes a reliable supply of estrogen patches resumes sooner rather than later – it’ll mean she and other transgender women, as well as other New Zealanders who need it, can go back to their “normal, life-changing” hormone regimes.