Narcotics Anonymous just celebrated 40 years in Aotearoa. Toby Manhire went along to the party.

On a sunny Saturday afternoon in the middle of last month, a couple of hundred people gathered in a suburban Auckland marae to celebrate a 40th birthday. “Naughty 40” posters were stuck to the walls. There were raffles and auctions. Nostalgic slideshows, nostalgic tunes. Someone played Madonna. Someone else played Prince. Old friends made beelines for one another, hugging like mad. There were speeches, lots of them. But because the birthday was for Narcotics Anonymous, marking four decades in New Zealand, each kicked off with the customary intro.

“Hi. My name is Sue and I am an addict.”

“Hi, Sue,” the room erupted in response.

“I’ve had the privilege to be part of NA for, oh my God, I don’t know how long – 30, 40 years,” said Sue. She summed it up this way: “Service, sponsorship, ciggies, sass. And all-round GCs.” (Sue is not her real name. Narcotics Anonymous meetings operate on a first-name-only basis, but I’ve gone full-anon and changed those throughout this piece.)

Sue and a string of other speakers recounted memories of the early days. Almost everyone mentioned the mountainous ashtrays and clouds of smoke – “sometimes you couldn’t see the other side of the room”. The landlines. The typed letters. One participant recalled finding out about NA through the Yellow Pages. Another, less fond memory: the times when police sniffed around meetings, when drug addiction was considered as criminality, not illness.

The name that came up most of all at the birthday event was Janet C. In a history of Narcotics Anonymous in Aotearoa, published in 2005, she was called “the key player in this story”. There had been precursor groups in the years before, including those convened by James K Baxter from 1969 – as vividly recounted in his poem ‘The Ballad of the Junkies and the Fuzz’ – but the NA that Janet imported from Sydney in 1982 would last. The sharing of those memories had a greater and more raw quality to them, because Janet was not there. Founder, talisman and “guiding light”, she died suddenly in June this year.

“Janet was eight years in recovery when I came in the door [in 1987]. I thought that was unbelievable, something beyond my reach,” said one contemporary. “Janet was incredible. She just kept us going and going,” said another. “I’m going to start crying if I talk about Janet,” said Ben, an NA member since the 80s and one of the organisers of the event, when we caught up the day before. And he did, as he described how she’d convened the first meetings on Thursday nights at 55 View Road, Mt Eden. They called it the “New View” fellowship, and the fellowship was set in motion.

The following year, meetings relocated to the St James Centre. By then there were four a week, and the place these days known as Hopetoun Alpha was a bit of a dive. “Remember that?” Anne asked the 40th birthday crowd to a sprinkle of nodding heads. “There were a few people here today who used to go. We didn’t have a toilet. There were busted sofas and people lying in the doorways. Narcotics Anonymous didn’t have a great name in those days.”

From those early, scrappy days, Narcotics Anonymous Aotearoa blossomed. Today there are 193 meetings a week across New Zealand, as part of a global network that traverses 144 countries. All of which is cause not just for reflection but celebration, said Ben. He’s been attending meetings since 1987. “We should be fucking proud of who we are and what we do.”

John Crace describes his encounter with NA in London in the late 80s, as he set about recovering from a heroin addiction, as life-changing. Until then, “my only frame of reference had been junkies who fell into two categories: alive or dead”, the journalist wrote in 2019. “I felt an intense sense of belonging. Like a family I had never known, who understood my life, my shame, my darkness. Anyone who had been clean for more than a couple of years was like a god to me.”

He wrote: “A day at a time. That was the mantra. I went to meetings. I took on a tea and coffee commitment. Mostly I sat at the back and listened, too shy and inarticulate to speak. In the early days, I had no sentences, not even words, to describe my feelings. Slowly, I discovered a voice, owned my pain and remade my life. I found I was still the person I had always been as a child. I was insecure, narcissistic, self-destructive and felt unloved, but I could live with those feelings without taking drugs.”

Narcotics Anonymous was born in California in the late ’40s and early ’50s, when a group of addicts led by someone called Jimmy K determined that their experiences and struggles warranted a setup distinct from Alcoholics Anonymous. Some AA members were less than keen to have people addicted to drugs other than alcohol in the mix. The philosophy of AA, with its 12 steps and 12 traditions, was and is very much the template for NA but each group retains its own personality. “AA is the mothership. We’re the bastard child,” said Ben. “We’re the disreputable, disheveled, dissolute one.”

As with AA, NA members talk about the “literature” of the organisation, at the heart of which is something called the Basic Text. It sets out the purpose like this: “NA is a nonprofit fellowship or society of men and women for whom drugs had become a major problem. We are recovering addicts who meet regularly to help each other stay clean.”

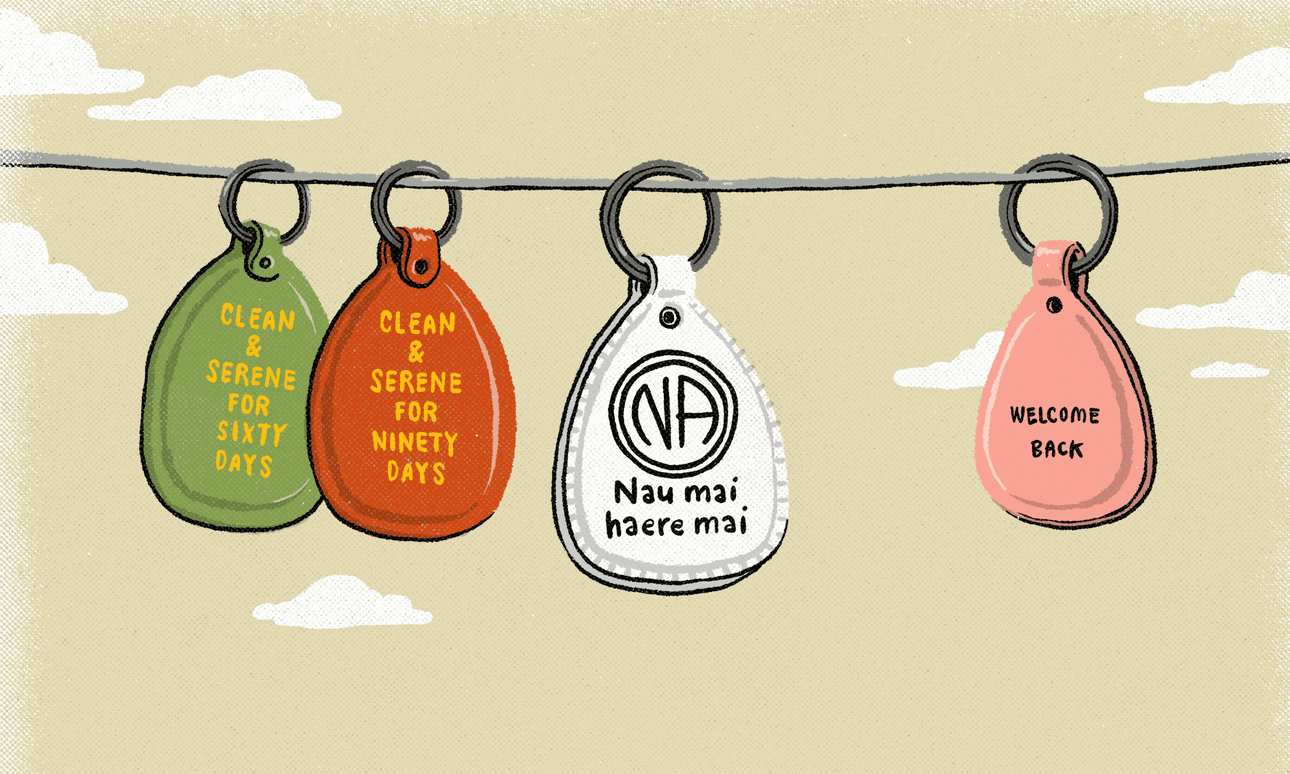

The programme is based on complete abstinence from addictive drugs – alcohol included – though the only requirement for attendance is “the desire to stop using”. At meetings, participants will typically gather in a circle and share their experiences of addiction and recovery, or simply sit and observe. Newbies are often welcomed with a key tag – other key tags are awarded for clean stretches: 30 days, 90 days, years.

All of it takes place away from the spotlight, open but not, by design, transparent – the clue is the name. It’s no wonder, then, that questions abound. Start typing “is Narcotics Anonymous” into Google and the first three offer to auto-complete the question are religious, free and effective.

To begin with the last of those: yes, it is effective, with successes born out in studies in New Zealand and abroad. But it is not for everyone. In a submission to the Aotearoa Mental Health and Addiction Inquiry in 2018 that laid out the approach and its record, a spokesperson said this: “NA is only one organisation among many addressing the problem of drug addiction. Narcotics Anonymous does not claim to have a programme that will work for all addicts under all circumstances, or that its therapeutic views should be universally adopted.”

Is it free? Yes, although members are invited to make small contributions to cover costs (the birthday event suggested $5).

And what about God? There is no mistaking the religious language, both in the publications and the gatherings. Fellowships. Texts. Faith and miracles. Meditations and prayers. The Basic Text explains, however: “Ours is a spiritual, not a religious programme … Anyone may join us regardless of age, race, sexual identity, creed, religion, or lack of religion.”

God is very clearly, however, in the house. The first of the 12 steps requires an acceptance of a powerlessness over addiction; the second reads, “We came to believe that a Power greater than ourselves could restore us to sanity.” And the third: “We made a decision to turn our will and our lives over to the care of God as we understood Him.”

There is a push in New Zealand and around the world to change some of that language, Ben told me – to swap out both “Him” and “God” for another term used in the literature: “higher power”.

That higher power, Ben said, could be anything. He cited Steve Earle, for whom God became suddenly “of paramount importance”. Musician, writer and face of NA in The Wire, Earle put it this way: “It’s absolutely necessary that I believe there’s a power greater than I am, or I’m fucked. Recovery is just completely and totally based on that. My spirituality is very simple: I believe there is a God and it ain’t me. And that’s as far as I’ve got.”

Ben echoed that maxim. His God? “All that matters is that it’s not me. It might be a group.” He pointed at his plate. “It might be this fucking curry, you know?”

After the birthday event, Ben emailed me again on the religion thing. “The 12 steps themselves began in the expressly Christian Oxford Group in the 1930s,” he wrote. “AA got kicked out for focusing too much on alcoholism and not enough Christ. Kind of sums us up, too. Have never heard that word [Christ] in NA.”

Ben’s translation of those first few steps: “The first step basically says, ‘I’m fucked,’ and the next two say, ‘I need and have to trust other people (unthinkable ha ha) to stay clean.’”

Then come the “heavy lifting” and “inventory work” of the fourth and fifth steps – in which the addict starts to deal with their world outside. “We all spend/spent anguished months writing out the story of our lives in exercise books, our deepest darkest, and reading that out to a trusted person, getting rid of all the shit that forces us to hate ourselves and self medicate,” wrote Ben. “A very ancient and rigorous process. For people suffering from sexual abuse and other kinds of trauma (most of NA tbh), this is terrifying but transformative. Oh and then we go and apologise to everyone we fucked over in the sixth and seventh steps. Good times …”

Ben seems to have found himself the unofficial historian of NA in Aotearoa, and he knows his subject, making repeated references to coverage of drugs – use, addiction, recovery – across literature and cinema, journalism and memoir.

He admires the accounts by Crace and the revered former New York Times columnist David Carr, who told his story in The Night of the Gun. Ben pointed to a passage by Carr which unpicks “the arc of the addict, warm and familiar as a Hallmark movie … In the convention of the recovery narrative, readers will want to scan past the tick-tock, looking for the yucky part so that they can feel better about themselves.”

Ben said: “That’s the challenge about writing about recovery, all those redemption songs after the slough of despond. Carr is funny on the banality of the NA slogans, the terror of becoming a Joe or Jane Lunchbox, when we were so fatally hip and terminally cool in ‘active’ (addiction). Worst of all (the very worst), of becoming a Christian, a tambourine man.”

The essence of the recovery story, really, is undramatic, even banal: the span of another day, the passage of time, the coming back. “The folks you sat with on Saturday,” Ben told me, “are all loosely involved in this kind of practice or know they have to be to stay clean, no longer occupying the chaos that Carr and Crace convey so brilliantly (which is just another day in the office to all of us). And as a result they are no longer dying, tying up the emergency services.”

What it is not, however, is stuffily didactic or earnest. The reality is looser, funnier. “There’s no piety,” said Ben. “Just a lot of camaraderie. We’re all trying to live. Become better people. Lead decent lives.” And there’s a “dark humour” that pervades many a meeting, he said. Plenty of members who are, like him, “constitutionally cynical”.

Janet C was a bit like that. She might have been regarded as something like a saint, but no one called her an angel. At the 40th, she was remembered as a hero, but also a mischief-maker and “party animal”. At Janet’s funeral, her son recalled, to roars of laughter, her appetite for a prank. Like the time she painted a McDonald’s sign with the words “opening soon” and erected it on the Piha hill, “just to wind up the locals”.

Ben began going to NA meetings in the late ’80s. He’d been working in Wellington, in a decent job, disguising his addiction to some; to others, to friends, he was an agent of chaos and misery. He and his fellow addicts were “just walking disaster zones”. They didn’t have relationships, not really. “Like they say, we just took hostages.” For a long time, “I just never believed I’d ever stop,” he said. “I needed those anaesthetics to live.” But Ben discovered the NA programme after being referred to a rehab clinic in Hanmer Springs. It worked. “I came back to town and it was a town full of ghosts – all these people I’d pissed off because I’d overdosed in their bedrooms or just been a fucking pest, you know?”

Today he has been clean for 35 years, but when I ask if he can now go a stretch without attending a meeting he shakes his head and looks at me like I’ve just confessed to murder. On a pre-Covid work trip in Europe he went along to meetings in France, the Netherlands and Germany. Each betrayed its own national stereotypes: copious small baked confections in Amsterdam; meticulously sliced apple in Berlin.

So what’s New Zealand’s unique trait, I asked, expecting him to say something about, I don’t know, pineapple lumps. “The whole Māori side,” he replied. “The aroha. So much aroha.”

Kaupapa Māori wasn’t always there. As an addict and single mum, Ros first attended an NA meeting in 1989. “At the time I was one of only a few people coming from a Māori background,” she said. “When I got to Narcotics Anonymous it was a largely white fellowship. I was 25, and I’d come from South Auckland. I’d never used heroin or a needle. But I’d come from a lot of trauma. A lot of physical and psychological abuse.”

At first she felt out of place, “When I came in, I saw the differences, but soon I started to see the similarities. The thing I battled with was fear and anxiety. I hyperventilated. But once I got my arse in the seat, and got on with the meeting, I’d feel calm, I’d feel connected. I’d get some relief from the madness that was sitting in my head.”

There were few Māori involved at the time, and most “didn’t understand tikanga, didn’t have te reo. Some of the early attempts at pōwhiri were a bit embarrassing, to say the least,” she said. “We’ve still got a way to go. We’ve still got a bit of growth to go. But we’ve come a long way. That’s the magic of this programme.”

Later in the afternoon, Steph spoke. “In those days it was very white,” she said of the first decade. “It was not a diverse fellowship.” Attitudes were different. “I remember the first time there was a suggestion of having an all-women’s meeting. Oh my lord, there was a lot of strife about that. The world was going to collapse.”

And the drugs were different, too. “Most of the people had been using opiates. Today it’s completely different,” said Steph. “It’s probably not very PC to say it but one of the things about meth is it brings people to their knees very quickly. So it really does mean there are more young people.”

NA looks a lot like a family tree. It concertinas outwards, and tumbles down through the generations. After a member has been around for a while, they may be asked to become a sponsor – a pastoral guide through the steps, a shoulder to cry on, someone to call. When the sponsored person becomes a sponsor in turn, the original sponsor becomes their great-sponsor, and so on.

“Hi, I’m Max and I’m an addict.”

“Hi, Max.”

“Looking around I can see my sponsees and my grand sponsee and my great grand sponsees. I love my sponsee with all my heart. They’re the reason I keep coming back.”

Max is transgender. “When I told people a few years ago that I was changing my gender, and that I was going to start looking really different, and would be using my correct pronouns, people did that. They made the space for me at meetings at a time when I was terrified about how people might perceive me. But it has been wonderful. People in this fellowship make space for me.”

At the 40th birthday, which stretched across five hours, speakers kept on coming back to, well, coming back. “It’s simple. You go to a meeting and you keep coming back,” said Steph. “I keep coming back because I’m an addict. Everything I tried to make my life better didn’t work. It was a big fail. This is the only thing that worked. I found the gift of recovery.”

Through it all the people of NA were living, breathing, surviving evidence that “change is possible”. She said: “We’re all in here. This is it. We’re all each other’s mirrors.”

For more on Narcotics Anonymous Aotearoa, see here.