‘Don’t call me racist for voting leave,’ wrote expat Kiwi and controversy magnet Alex Hazlehurst earlier this week. How about we call you short-sighted, self-centred and sadly misinformed instead, suggests New Zealand-born Londoner Paul Gallagher.

Dear Alex,

The upheaval and recriminations following the EU referendum result have seemingly left everyone in the UK on edge. You have faced abuse for choosing to vote leave, and have every right to feel angry about that. You have conducted research and while your opinions are your own, it’s fair to say that I completely disagree with your conclusions.

You have taken offence at name calling. You are annoyed at feeling lumped into the same category as racists. With all due respect, this isn’t really about you. Where is your empathy and perspective about what is going on around you? You have expressed outrage about the word “racist” without addressing the numerous instances of racially motivated abuse seen in recent days. Whether you are comfortable with it or not, your choice to vote leave means that you were on the same side as some pretty horrible people. I’m sorry, but it’s up to you to find a way to be at peace with that.

Anyone who claims that all leave voters are racists or xenophobic is clearly a reductionist fool. But you’d surely admit the debate brought out the worst in people – as did the result. You claim that if someone was called racist in New Zealand it would be reported from Kaitaia to Gore. I think you’re selling New Zealanders a bit short. It may be true that some people aren’t comfortable about confronting them, but they’re not all that naive or fragile about race issues. Why? Because racism exists in New Zealand. What would shock New Zealanders would be hate crimes or, say, the killing of a member of parliament. Hate crimes have risen dramatically in the UK since the referendum, from the firebombing of businesses owned by Muslims to messages describing immigrants as “vermin” or “scum”.

You are right: the debate around the referendum descended into an embarrassing level of scaremongering and childishness. From the start the whole process has felt grubby. The campaign made for uncomfortable bedfellows. Younger progressive voters found themselves casting their vote in support of the Tory tag team behind one of the harshest periods of austerity this country has ever faced. They also lined up alongside the institutions of the City, where “corporate responsibility” and “operating within the bounds of the law” have been shown to be tongue-in-cheek terms. The Leave campaign saw traditional Labour strongholds lining up alongside far-right nationalists and people from across the spectrum who feel left behind by the political and economic elites. The leave campaign was led by a journalist who was once fired for making stuff up, and a former commodities trader from the City who hijacked a political party by developing the persona of a pint-swilling “man of the people” to, in part, rail against the elites of whom he has long been a member.

All in all, it has created a peculiar climate. The ructions created will take years, if not generations, to resolve. The Tories have found themselves leaderless, and Labour ranks are further divided by factional infighting and an identity crisis not uncommon among labour movements the world over. David Cameron has washed his hands of the whole thing, Boris Johnson’s career appears in tatters, and Nigel Farage has just resigned for the second time in 12 months. Jeremy Corbyn may retain the popular support of Labour Party members, but cabals within the party organisation suggest that he is a dead man walking.

I am not so blind as to think there were not valid reasons to vote leave. There is a level of anger among the working class, and in provincial areas where people feel they have worked too hard for too little in order to service London’s excesses. That is more than enough to spark a vote of protest against the elites, either in Westminster or in Brussels. A lot of people, particularly in the traditional Labour heartlands, appear to have voted against the wishes of David Cameron simply out of sheer frustration. There are also those on the left who consider that voting leave was a protest against the entanglement of neoliberal ideology. That too is a perfectly legitimate reason to vote leave, albeit one I don’t personally agree with.

You point to sovereignty as your primary reason for voting leave. Sovereignty is a fickle and unwieldy concept in the modern era. Historically speaking, Britain has not exactly been shy about asserting its sovereignty in order to maintain its power and interests on the world stage. When Britain ruled the waves, and diplomacy was delivered through gunboats rather than soft power, sovereignty was enough to justify all sorts of acts of realpolitik. But in today’s context it’s a more nuanced issue. The assertion of sovereignty comes with a sense of the “other”, an accentuation of differences, a drawing of a line in the sand.

Like all countries, Britain cedes a certain level of sovereignty to participate in international affairs and trade: whether it is Nato (the Article 5 obligation to defend fellow members), the World Trade Organisation (with powers of arbitration and regulation), or even the Commonwealth (now there’s a club that the UK should try leaving!). These decisions to dilute absolute control are considered to be worthwhile trade-offs for national security or economic prosperity. In a world of cooperation and interconnectivity, sovereignty is not a fixed commodity to be guarded jealously. It is something to be shared. All states are sovereign, but some are more sovereign than others. Far be it from me to promote a former Tory prime minister as a voice of reason, but John Major does make a trenchant point about exactly which nation state is the most sovereign.

Britain is the fifth largest economy in the world. You are correct that in the long term it will survive any turmoil caused by Brexit. However, trade with the EU is vital – whether it remains inside or out. Less than 10% of EU exports come into Britain, but half of all British exports go to the EU. Obviously that relationship will continue, albeit with different – less attractive – terms of trade. Whether they like it or not, UK producers will have to continue to abide by those pesky EU regulations (things like health and safety standards) in order to export to the EU. Britain is set to find itself on the sidelines of its largest trading bloc: it will be independent from, but will definitively remain bound by, rules it no longer has any influence over. What use is a nominal assertion of sovereignty, other than being a hollow form of victory?

Walking home from work along Essex Road last week, I witnessed leave voters with their drunken chants of “This is OUR England!” That sort of rhetoric delivers a certain message to the people of Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland, who aren’t unaware about issues of devolution. What of the sovereignty of Scotland, a country that voted overwhelmingly to remain in the EU – only to then find its wishes discounted by those of an English majority? Chalk that one up as a victory for democracy, I guess.

British sovereignty has not been propped up since the vote: Scotland will no doubt seek another vote on independence, Northern Ireland may consider leaving, and Wales too will no doubt debate its own future. There is utter nonsense too: calls to partition London off as its own separate state. All this doesn’t add up to a stronger United Kingdom.

Immigration was not the chief reason for your decision, yet it’s clear that it was a significant influence. You ask whether it is fair that, say, baristas from the EU have been able to come to live in the UK without hindrance while New Zealanders face visa restrictions. Putting aside the fact that those EU baristas would have to contend with members of the New Zealand coffee mafia already standing behind many of Britain’s espresso machines, the short answer, of course, is yes. It’s a reciprocal arrangement in which migration goes both ways. Around 3.3 million non-British EU citizens live in the UK, out of a population of about 434 million people (an estimate of the total EU population minus the UK population). That’s 0.76% of the non-British EU population living in the UK. On the other hand, 1.2 million British people live in other EU countries (predominantly in Spain, Ireland and France). That equates to around 1.8% of the UK population.

Even accounting for a margin of error, that’s a telling statistic. Proportionally speaking, more British people enjoy the benefits of living in the EU than the other way round. You might well argue that net migration to the UK is increasing and will only keep on increasing if Britain remains in the EU. Brexit or not, that is likely to be the case anyway. And indeed, increasing numbers of British people are moving abroad – no doubt keen to enjoy the freedom of movement that they have been hearing so much about!

What you’re really asking is whether it’s fair for EU citizens to have rights that hard-working and talented New Zealanders such as yourself do not. You feel that Britain leaving the EU might eventually create positive outcomes for Commonwealth citizens: you might get to stay here longer if the UK government looks more favourably towards New Zealanders. The poster boy of the leave camp clearly endorses the idea of New Zealanders gaining greater freedoms in the UK. As someone clearly aware of your two-year visa and the ticking clock, it seems to me that you based your decision upon a healthy level of self-interest. There’s absolutely no shame in that, but be a little more upfront about it. As a migrant, of course you don’t have a problem with immigration. You just have a problem with the current system of immigration, in the way that it relates to you. The circumstances of New Zealanders in the UK has virtually nothing to do with the EU referendum, but that’s beside the point. It is also, I would imagine, a handy editorial peg for the NZ Herald to hang its piqued interest on.

This is also where advocating so strongly for sovereignty may come back to bite. The leave camp campaigned rigidly to “take back control” of the UK borders. That may negatively affect people from Poland and New Zealand alike. You say you would like Commonwealth countries to have a level playing field with EU citizens. That could mean one of two things. You may mean that you want to punitively restrict the rights of about 434 million people from 27 countries so that they face the same visa restrictions as you currently do. Or you may prefer that the UK extends the rights currently enjoyed by EU citizens to all Commonwealth countries – potentially including 2.4 billion people from 52 other nations. I can see that idea impressing your fellow leave voters.

I’m not an objective observer in all this either: I have my own selfish reasons for voting remain. As a New Zealander and a British citizen, I can come and go as I please. But that might not always be the case for my partner, who is an EU citizen. Like you and me, she’s incredibly hard-working and very talented too. A likely scenario is that she would be eligible for some as-yet-undetermined-because-no-one-has-a-clue-what-is-going-on ¯\_(ツ)_/¯ loophole that will enable her to stay in the UK. But that is by no means assured. Extrapolate that out to the thousands upon thousands of people across the UK who may be facing similar levels of uncertainty. Why should, say, a Romanian person be torn from the loving embrace of their partner in, um, Rhyl? In a less emotional sense, what would happen if EU citizens had to leave the UK workforce? Let’s use the NHS – the jewel in the crown of British social services – as a template. The UK is heavily reliant on overseas health workers: 10% of all doctors and 4% of all nurses are EU citizens. Are they replaceable? Sure. Would their departure create a shortfall in services or difficulties in the retention of other staff? Probably.

Other possible implications of the Brexit vote make me nervous. Continued peace in Northern Ireland is something to consider. That may not be on your checklist of important issues, but coming as I do from a family affected by the brutal violence of the Troubles, I understand some of the nuances involved. If the hills of Armagh become part of the UK’s only land border with the EU, there will be a deep and unhappy symbolism associated with those border controls. The Northern Irish are not so devoid of pragmatism that they wouldn’t be able to make it work. But what good can come of exposing only recently healed wounds? Let’s make another toast to that heightened sense of sovereignty.

I also worry for the rights of low and middle-income workers in the UK, who currently have protections under same EU laws that you are opposed to. Hell, they are the very same protections that you enjoy. You identify the Lisbon Treaty as a particular area of concern. That helped enshrine into law the Charter of Fundamental Human Rights of the European Union, including overbearing namby-pamby things like rights to privacy, the rights of a child, rights for workers, freedoms from discrimination, the right to a fair trial, and the right to avoid things like torture, capital punishment and slavery.

Far from the EU imposing a “one size fits all” rule, the UK was able to negotiate certain opt-out protocols relating to the Schengen Agreement, economic and monetary union, justice, and aspects of human rights agreements. And contrary to your claims about negotiations being unmovable, David Cameron recently went to Brussels and renegotiated aspects of the UK’s relationship with the EU – reforms that now will never be implemented.

You envisage Britain being proud of the Brexit decision in a decade’s time. What about people living in the now? What the referendum has brutally underlined is the deep level of inequality in the UK. Austerity budgets, welfare cuts, the increase in tertiary education costs, the eating away at the margins of the NHS, and the imbalance of public spending all threaten the UK’s already tattered social fabric. There is deep fear among people already living from payday to payday, and indeed not making ends meet at all. I volunteer in a food bank and the demand for our services is increasing dramatically. It’s not symptomatic of there being too much immigration – instead, it’s more to do with brutal welfare cuts and benefits sanctions imposed by the Conservative government. While Brussels is a handy scapegoat for social ills, it definitely does not tell the whole story.

Scaremongering or not, there are real consequences that will have to be considered for questions that don’t have immediate answers. Agricultural subsidies and protections for cottage industries will come to an end. Certainly, they’ll be replaced by something – but what, and when? Upheaval is already being felt by small businesses in terms of lost contracts and staff cuts. That will spread to larger companies and sectors like manufacturing as the weeks drag on. Perhaps of interest to you, New Zealanders may also find the going tough, as uncertainty and dreary economic forecasts make it less likely for workplaces to sponsor them.

Respectfully, I would suggest that your presence in the UK is contributing – in its own very small way – to the social inequality that has sparked much of the anger felt across parts of the UK. That is not meant to offend, but to give pause for thought. You claim in your piece that you are being discriminated against. I fail to see how. All New Zealanders who make the effort can enjoy the opportunity to live and work in the UK. If indeed people in the UK are suffering due to competition for employment and housing, then let us be honest that we are part of that problem. I’m not saying for a moment that we shouldn’t be here, but we sure as hell need to recognise the privileges we enjoy.

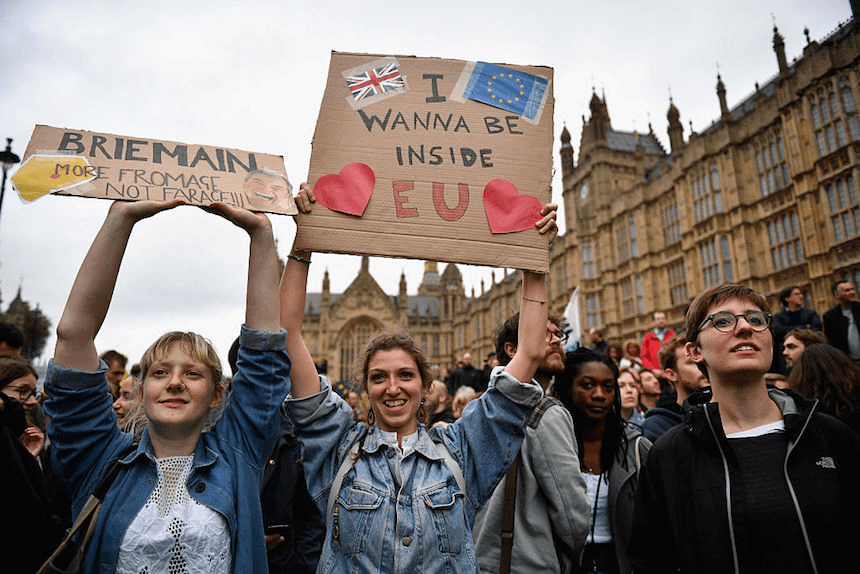

You express scepticism about people who marched against the Brexit result in London a few days ago. Let’s be clear, there is nothing more positive than tens of thousands of people walking in solidarity with each other, and with those they see as their European brothers and sisters. I share those values and agree with the concept of the European family. I’ve got the T-shirt and everything. I understand that you don’t share those values, and indeed have no motivation to do so considering you are not an EU citizen. But I am an EU citizen, and I would love to remain one. The people who marched chose to focus on the positives of togetherness – and I stand together with them.

The irony is not lost on me that by rejecting one system influenced by an unelected bureaucratic elite, leave voters in the UK may – if a snap election is not forthcoming – find themselves governed for the next four years by an unelected prime minister.

Politics is by no means an exact science, and no one holds all of the answers. Good on you for exercising your democratic right when plenty of others did not. But despite the strength of your political conviction, your two-year visa brings up a pertinent point: you are here for a good time, not a long time. You don’t have to worry about what is around the corner. You are here for the experiences, the memories, the souvenirs.

By all means, Brexit through the gift shop.

Paul.

PS You originally wrote in your piece that the EU parliament is unelected. It’s a significant error, and a correction was made without acknowledgement. The EU parliament is elected: indeed, Ukip currently has the largest number of seats out of all the UK political parties. Incidentally, the right to vote for the EU parliament is found in that document you don’t like, the Charter of Fundamental Human Rights of the European Union.