I was told to avoid gluten. I was told it was all in my head. When 10% of women experience endometriosis, why does it take so long for its classic symptoms to be recognised?

It was 2011 when I had my first period. It felt like a very exciting moment in my life, like I was finally becoming a woman. This excitement was short-lived, however. By 2013 I had experienced my first ruptured ovarian cyst, and high school was a time of life when my periods were so heavy and so painful that it felt almost impossible to get through the week.

At the age of 14 I went to the GP with my mum to discuss our shared concern about my pain. Much like every other girl it seemed I was promptly put on the contraceptive pill. For a short time this seemed to reduce my pain, but I’ve come to recognise this pain is much like a shadow, always nearby. Not long after starting the pill I began to notice other symptoms – including digestive and bowel issues which, at 16, I was told were all a result of IBS and a gluten intolerance. By the time I was 17 I had gone through five different contraceptive pills attempting to find one that worked for my increasingly painful and erratic periods.

I can’t recall the number of times I went to various GPs in the hope of figuring out what was wrong with me. Every time I was given a script or told that it was normal, in my head or just part of being a woman. It truly got to the point where I began to believe that I was overdramatic and had the pain threshold of a toddler. The only thing that kept me from believing it was all my head was the support of my family and partner.

In 2020, during the first lockdown, I realised that I had had my period consistently for seven weeks. I don’t think it phased me so much as I wasn’t really doing anything, but nonetheless, I mentioned it to my GP who suggested I take my contraceptive pills back-to-back (no sugar pills). Two years later that GP left the practice and I thought I would make one last-ditch effort to try and speak to someone about my situation. This was when the rug was pulled out from under me. I went in for an internal and external ultrasound where the radiographer told me it appeared that my left ovary was immobile (would not move when probed) and she suspected I had endometriosis. Following this I received a text from my GP that my scan had come back normal. I remember feeling so deflated by this news. After a conversation with my mum decided I would ring a surgeon that the radiographer had suggested.

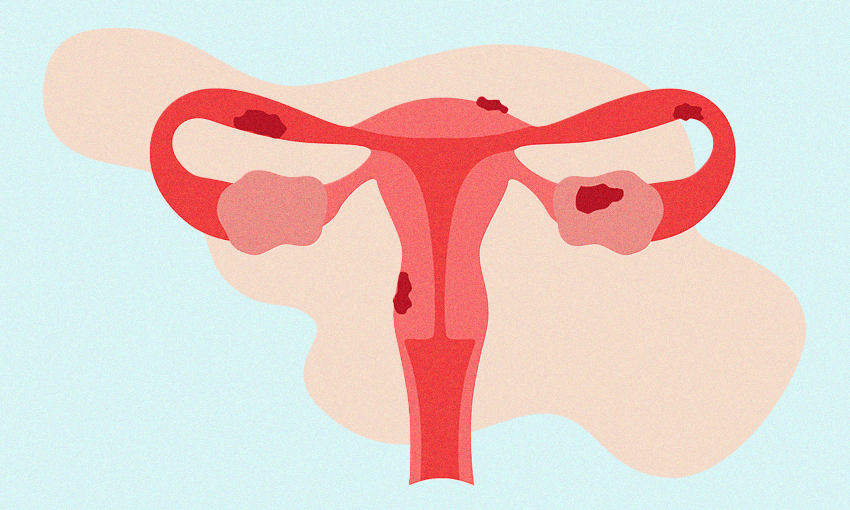

I was thankful that surgeon agreed to see me without a referral. My consultation with him was the most remarkable experience. I felt so heard. Shortly after this, in December of 2022, I was booked in for a laparoscopy. After years of being told that what I was experiencing was “normal” I was deeply afraid that he would find nothing wrong with me (especially as I was having the surgery done privately and my mum was having to pay 20% of it). My first words in recovery when I woke up was “did he find anything?” The nurse said “yes” and cried, saying “it’s happy tears, it’s happy tears!” My surgeon diagnosed me with stage three endometriosis that had to be removed from several parts of my bowel, bladder, pelvic sidewalls, and where my appendix had previously been removed. On top of this I received multiple nerve blocks and Botox to remedy the damage done to my pelvic floor and nerves.

My diagnosis is not uncommon, and nor is my frustrating experience. One in ten women have endometriosis – the rate is significantly higher still for the transgender population – and yet it takes an average of seven years to receive a diagnosis and in the New Zealand public system a further three years to get surgery. That’s a decade to receive help. I was so fortunate that I had access to private care as I was told if left much longer, I could have lost my ability to have children. Not everyone with endometriosis gets this luxury.

I would like to see teenagers taught about these conditions in school and told what to look for, and for conversations about everyone’s health to become less taboo. I wish so much that a person suffering could go to a doctor and be heard the first time. One of the hardest parts of my experience, beyond getting a diagnosis, was the ability to access information on what endometriosis is or what it meant to have the disease. I learnt most of what I know from social media.

I spent countless days doubled over in pain only able to muster enough energy to get a hot water bottle and curl up in bed. I cancelled plans with friends and family myriad times. The impact that this disease has had on me is so significant, not least its toll on my mental health. I look back often on all the memories I have that were hindered by pain or the things that I missed out on as a result of it. My hope is that, with better recognition, all those who have endometriosis will get better support, access to healthcare and future generations won’t have to wait seven years for a diagnosis. Until then, my message to anyone having an experience like mine is to trust in yourself and your body.