For more than five years Mike Smith and a voluntary legal team have been pulling legal strings to hold NZ’s seven highest polluters accountable. The case, struck out multiple times, was reinstated by the supreme court yesterday.

Mike Smith is heading to court. Again. The man who famously went to court for cutting down the one tree on One Tree Hill in an act of protest, wants to sue New Zealand’s biggest polluting companies – and the Supreme Court has said he can. It ruled that the claim made by Smith against Fonterra, Genesis Energy, Dairy Holdings, NZ Steel, Z Energy, Channel Infrastructure and BT Mining, for damages to his whenua and moana, should be allowed to go to trial. And that’s because the court considers his case tenable.

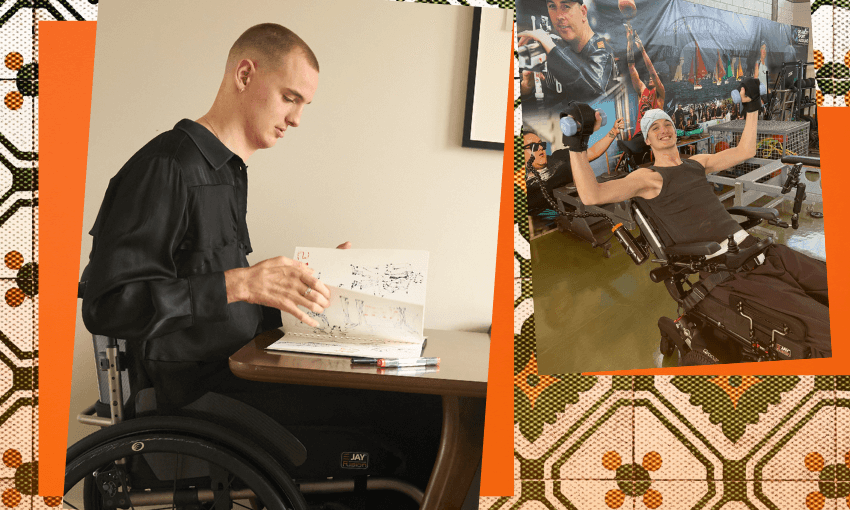

Smith, an elder of Ngāpuhi and Ngāti Kahu and a climate change spokesperson for the Iwi Chairs Forum, has been trying to sue these companies, saying that the corporations are damaging his whenua and moana, and causing him harm. He first filed a statement of claim against what he calls the “polluting seven” at the High Court in August 2019. Now, he says he can’t wait to “get these polluting companies into the dock and to interrogate them”.

The seven companies haven’t broken any written law or regulation passed by parliament. Instead, Smith’s case calls on torts, which aren’t written and passed by parliament but instead are made by judges drawing on principles of fairness and common sense. In particular, Smith is saying the companies should be held accountable under negligence and public nuisance, and that a new tort to cover climate harm should be made.

Previously, Smith’s case was struck-out by the Court of Appeal because it considered the issue of climate change so big and complex that it should be dealt with at a government level, and in fact already is through regulation. The Supreme Court assessed that claim and concluded the opposite, that parliament has “left a pathway open for the common law to operate, develop and evolve (if that is thought to be required in this case) amid a statutory landscape that does not displace the common law by the interposition of permits, immunities, policies, rules and resource consents.”

The Court of Appeal had also found that Smith’s pleas to consider tikanga principles did not assist in his claim in tort laws. Yesterday’s ruling by the Supreme Court instead found previous instances, dating back to 1866, where tikanga has already informed the application and formulation of tort laws. During the hearing in August 2022, Te Hunga Rōia Māori o Aotearoa made a submission stating that common law must evolve within the context and needs of New Zealand, and that tikanga is a part of that. The ruling stated that the court will have to consider tikanga conceptions of loss that extends beyond physical and economic, name as Smith’s connection to his whenua, and tikanga principles provide a foundation for his claims that environmental harm is a harm in and of itself, which in turn harms kaitiaki and mana whenua.

For the Supreme Court to consider his case tenable is a “really significant and welcome development in the law,” says Jessica Palairet, executive director of Lawyers for Climate Action, a group that supported Smith’s appeal in court. The courts have never before recognised any sort of duty not to contribute to climate change outside of parliament-made regulations. “It is really exciting that the Supreme Court has opened the door for these arguments,” she says. Because other Commonwealth countries also have tort law, it’s a precedent which could have an impact in climate change law around the world, making it a “significant milestone.”

Though the ruling provides new ways to apply tort laws to issues of the environment and climate harm, “I doubt this is going to open floodgates,” says Palairet. She’s not expecting thousands more cases to be brought forward because the threshold is still high, and putting together a case is no easy thing. Still, “it’s really significant that it’s possible that claims against major emitting companies could be made.”

Through the trial, Smith will seek a suspended injunction, a legal court order which would require the companies to reach zero emissions by 2050, or alternatively, immediately. But of course, making it to trial in no way means you will win that trial. No dates have been set, but Smith says he’s looking forward to the courtroom battle, and that the team is “feeling fighting fit, and morale is high as a result of this decision.”