How important is accessibility when it comes to enjoying and appreciating our art? Sam Brooks reviews Blanc de Blanc and The Magic Flute, both part of the Auckland Arts Festival.

Accessibility means a range of different things when it comes to art.

The first thing that might come to mind is the physical accessibility; how accessible is your art to get to for someone that is otherly abled? Are there performances of your work that are available for those with impairments that might prevent them from engaging with that work? When we think about accessibility, this is where our thoughts might stop. (And frankly, it should be a stop-and-discuss, because not enough of our venues or festivals are doing well on this front.)

There are other forms of accessibility to consider as well.

Financial accessibility; how expensive is the art you’re putting on, and are there ways for someone with less financial means to engage with your art? Also, does the length of the work you’re putting on, say a three hour play where people yell and throw the kitchen sink at each other, make it inaccessible for people who have to pay for parking, transport, childcare?

Then there’s more nebulous, moveable forms of accessibility. For example, can someone straight off the street walk in and engage with your art on an equal level, or do they need to be trained to engage with it? I’m not talking about appreciation here, appreciation has little to do with accessibility, I’m talking about the ability to engage with the work at all. Anyone can bop along to, say, Carly Rae Jepsen’s ‘Call Me Maybe’, but something like Laurie Anderson’s ‘O Superman’ might need a little bit more knowledge and context to engage with fully.

And finally, ideological accessibility. Are the ideas expressed within your work so backwards, so representative of a time that was uninhabitable for so many people, that it may be inaccessible or at the very least repellant, to somebody living in the current day?

Blanc de Blanc and The Magic Flute have very little to do with each other – other than potentially the proximity and high ticket price – but they’re worth discussing in terms of how accessible they are to an audience, and how much they’re doing to make their form accessible.

Blanc de Blanc occupies the now ubiquitous spot in the middle of Aotea Square during the Festival that seems reserved for the crowdpleasing circus-cabaret-burlesque hybrid show. These are fun, silly, and engaging shows that allow you to turn your brain off and your serotonin on. It’s the kind of show that you take your workmates to for a good time, along with as much wine as you’re allowed to carry in either hand.

Circus, cabaret and burlesque are accessible artforms. They’re as interactive and engaging as art can get without literally requiring the bane of every awkward audience member: audience interaction. They’re full of visual spectacle, and in the case of circus, full of awe. There’s an incredibly unique feeling in seeing somebody do something with their body that feels like sorcery. It’s almost divine, almost profane. Humans shouldn’t be able to do this, and yet they can.

Blanc de Blanc gives us all these thrills.

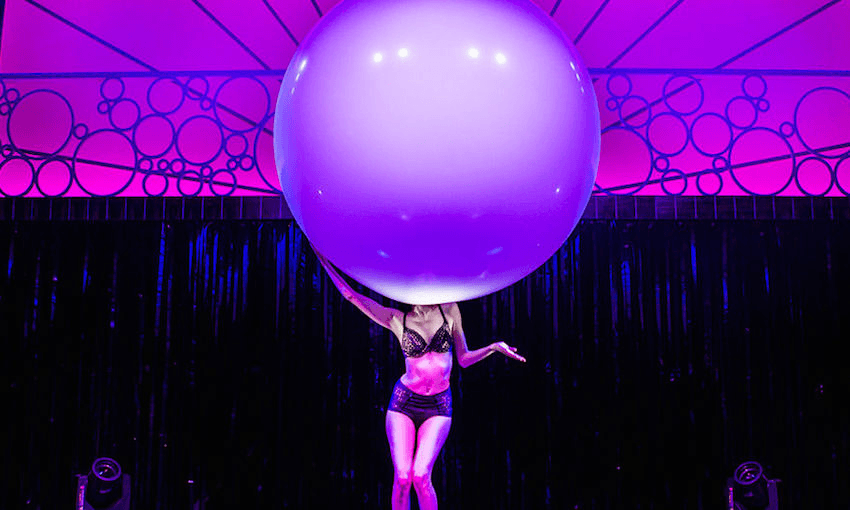

A couple performing an aerial tete-a-tete to Duke Dumont’s underrated club banger, ‘Melt’, while dipping in and out of a hot tub is visually stunning, and occasionally quite moving. A woman manoeuvring around a huge balloon that she has her head stuck in is hilarious, and engaging because we have no idea how she does it. Another woman spinning up to eight hoops around her entire body is frankly dizzying, and enough to bring forth an ‘oh my god!’ from my workmate.

It’s a guaranteed great time, unless you’re one of those people for whom the pleasure of circus has been dulled. In which case, I’m sorry, and I can do nothing for you. Someone spinning around in the air, defying gravity and the limits of the human body is always going to give me a little thrill.

Other the other hand, The Magic Flute is, you know, the Mozart opera The Magic Flute.

The opera with that one song with all the crazy high notes. The one that you probably learned songs from on the piano when you were a kid, as my co-worker realised midway during the show. The one that’s not a tragedy, but is actually meant to be kind of funny. (There’s apparently lots of opera that is kind of funny, but I’ve yet to meet a person who goes to the opera to get their comedy.)

This production has sold out and been acclaimed around the world, and for good reason. It comes from two acclaimed companies, the German opera company Komische Oper Berlin and the UK theatre company 1927. With the exception of the performers, the entire opera is animated.

The performers move with and around the live animation throughout, in a way that I would suspect most people would have first seen in Beyonce’s Billboard Music Awards performance of ‘Run The World (Girls)’. Live performers sync up with pre-recorded animation, popping hearts, moving legs, that sort of thing. When it’s frame perfect, it’s stunning, and gives the same kind of pleasure jolt that you get from seeing somebody spin around in the air.

The music is beautiful, and I assume well-performed by the Auckland Philharmonia Orchestra. Despite the beauty, and the achievement, there’s an inherent misogyny at the core of The Magic Flute. It’s a show where women are the source of chaos, men are the ones who right the wrongs, and not even the coded ending, which seems to be setting up the marriage between Tamino and Pamina as the start of some sort of fascist regime, cannot save it from the misogyny deep at its core.

I’m not here to debate the value of performing The Magic Flute in 2019. If you want to read about that, I’d direct you to Alex Taylor’s excellent criticism of the New Zealand Opera’s production of The Magic Flute three years ago, which discusses this in-depth. But it’s important to discuss its accessibility in 2019.

Opera is not the most accessible artform, in that there are a lot of barriers to engaging with it, and even more to appreciating it. It is often prohibitively expensive. It is long. It is often in a foreign language. It requires some form of training, as an audience member, to engage with; the easiest way to understand narrative is not having it sung at you. (Shrek: The Musical might prove me wrong here, unfortunately.)

These are all barriers to accessing it. You can’t bring somebody straight off the street, sit them down in front of The Magic Flute, and expect them to enjoy it or get the same appreciation as someone who has been watching opera all their life.

This doesn’t decrease its value, of course it doesn’t. If opera was of no value, it wouldn’t still be around and wouldn’t still be performed. It also doesn’t take away from the people who have spent their lives seeing opera, who engage with it, love it, and reckon with the immense talent and skill it takes to perform it.

But at some stage, as an audience member, you have to ask yourself the question. Is it worth engaging with a piece of art that does not in any way concern or relate to you, and has made little effort to relate to you? The length of the show made me dubious going into it, I felt like I was missing a lot of the potential value and achievements of the artist because of my lack of knowledge of the form while I was in it, and the misogyny made me uncomfortable and gross coming out of it.

Which is not to say there is no value in The Magic Flute. There are images in this production that will stay with me for quite a while – namely, the Queen of the Night being portrayed as a Shelob-esque spider monster with jerky, haunting blade-like legs stabbing down at Tamino. I can say the same for Blanc de Blanc, and god knows, it has bumped ‘Melt’ up my most played on Spotify.

Which is to say, compared to Blanc de Blanc, a show most concerned with its audience having the best time possible, The Magic Flute feels inaccessible. I might not know how the performers are doing what they’re doing, and for some of the circus acts, the entire point is not knowing how they’re doing these wondrous tricks. Even me, someone who has seen more circus than your average punter, gets the same amount of pleasure out of it as my workmate sitting next to me who has seen no circus. There are few barriers to accessing, and enjoying this show.

An Arts Festival exists to bring these kinds of experiences, though. It allows us to engage with art we might not otherwise engage with, and enrich our lives as a result. That’s the point of these festivals. If, for some reason, I was compelled to educate somebody about The Magic Flute, this is the production I would probably take them to. It feels like a great gateway drug to enjoying opera.

But, if I was to be asked by a stranger on the street what to go and see in the Arts Festival, the show that was most guaranteed to give them a good time, I’d send them to Blanc de Blanc. It’s not Mozart, but they’ll have a great time.

How valuable a piece of art is isn’t defined by the ticket price or how many people praise it. The value of a piece of art is incredibly subjective and personal, goodness knows my love for The Hours is not a universal declaration of its value. But when someone can’t even access your art, when there are so many barriers preventing them from accessing it, how are they supposed to value it in the first place?

The Magic Flute runs from March 8-March 10 as part of Auckland Arts Festival. Blanc de Blanc runs throughout the entire Auckland Arts Festival.