The best way to remember Peter is by living out the values he embodied, writes Dudley Benson.

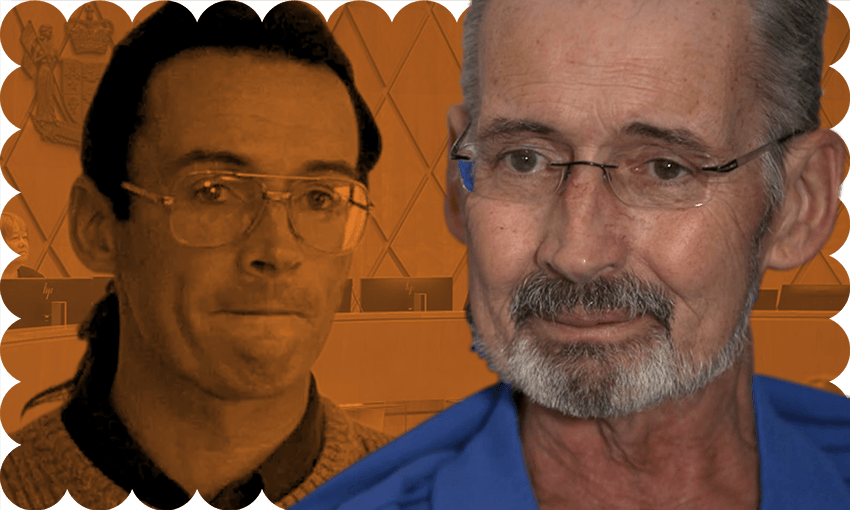

In queer Aotearoa history, I can’t think of a person who has symbolised as much suffering as Peter Ellis. The perception of this man and his role in the devastating Christchurch Civic Creche child sexual abuse case of the early 1990s has slowly changed since that hysteria-driven time: Peter is now seen less as the gay boogeyman he was cast to be, and more as the primary victim of an outrageous injustice that has only to a certain extent been alleviated with the Supreme Court’s quashing of his convictions.

But in the 30 years since Peter was convicted there’s been a cloud of silence around what happened to him, and to the other victims of this case. Though he has maintained a solid block of supporters, I wonder why on a broader level we haven’t rallied, why we haven’t protested in our collective anger. And I wonder why now, with the Supreme Court’s decision, certain people have been quick to offer their online RIPs, but fail to see the hypocrisy of their own casual transphobic and homophobic attitudes – the kind of attitudes that “othered” Peter Ellis. It’s these very same attitudes that in 1992 went on to destroy people’s lives, and caused immeasurable damage to our society.

Like Peter Ellis, I’m a queer man who grew up in Christchurch. It’s a city that rewards conformity, and certain ideals; it’s not a place known for political resistance, or as a safe haven for people who offer an alternative way of presenting to the world. Christchurch’s ingrained issues with homophobia and white supremacy run deep – it’s no coincidence that conspiracy-oriented far-right groups take hold there and march largely unchallenged through its streets. Thirty years ago it was even worse. The conditions were ripe for someone like Peter Ellis, who wore nail polish and affected a level of camp, to become a scapegoat for the fears of an irrational parent prone to accusations of child abuse, an overzealous and underqualified child psychiatrist, and the hot oil they’d go on to pour over this community.

The story is both profoundly complex and enragingly clear-cut. Lynley Hood tells it best in the book A City Possessed, but in summary: In 1992, Peter Ellis, an openly gay man, was charged with sexually abusing 20 children at the Civic Creche (reduced from an initial 45) where he worked. The police investigation included claims of what we might sadly consider familiar-sounding molestation charges, but also a multitude of outlandish ones: children buried in coffins, sacrifices, accomplices, and bizarre acts of logic-defying cruelty – all gleaned from interviews with children by an inexperienced supervising psychiatrist and team of social workers. Four of Peter’s female colleagues were also arrested, but their charges were eventually dropped. Peter was convicted of violations against seven children, and sentenced to 10 years; he served seven, maintaining his innocence, and was nominated by his fellow prisoners to be their union representative. Meanwhile, children grew up believing they’d been sexually abused, and no doubt some still do – victims not of Peter Ellis, but of the agendas of the adults around them.

About nine years after Peter’s arrest, at the age of 18, I came out as gay. My father’s response was to try to mute or temper the recognisable and openly gay man he feared I would be perceived as. He told me outright that people would think I was a paedophile. I was furious at the time, and for years after. But what I realise now is that to a certain extent, he was right. We had all lived through a cataclysmic event with the Civic Creche case. The number of men applying to train as teachers dropped dramatically, for fear of being seen as paedophiles, and therefore, fewer male role models existed in the lives of young people in Aotearoa for at least two decades. I have a memory of a group of men on a current affairs show – I think it was Holmes – saying they felt less inclined to be physically affectionate with their kids as a result of what happened to Peter. I’ve sometimes felt awkward and hyper-aware around hugging my friends’ kids, for the same reasons. There’s no way to measure this loss, other than to name it for what it is – a tragedy.

This year, I’ve been called a “pedo” online more times than I can count – oddly, because my queer-run business, a bar in Dunedin called Woof!, has been firm in its Covid health response. In their efforts to agenda-surf and isolate minority groups, the far-right anti-vax movement has now fixed their bloodshot eye on the rainbow community. They wallow in and spread disinformation that queer and trans people are “groomers” – their new favourite word – and that to be queer or trans is to be a paedophile. The abuse has radicalised me, and I’ve become an activist against disinformation, and the targeting of my community. I hope Peter would be proud of this.

How do we remember Peter Ellis, and what happened to him? And how do we avoid re-spawning a variation of the hellish saga of the Civic Creche? His story will no doubt inspire films, podcasts, maybe songs. To truly honour Peter and his experience, though – to demonstrate our desire to never have this happen again – will require more than just remembering. We have to live out the values that Peter embodied: an embrace of our unique individuality, and of outwardly presenting to the world the way we feel on the inside. If you’re a guy and want to wear nail polish – do it. If you want to dye your hair blue and change your pronouns – do it. But most crucially, we must check our judgment of others when they choose to express themselves in ways that we don’t initially understand. Proceeding with empathy and curiosity is far more powerful and unifying, than falling back on fear and disdain. And though I will never be able to talk with Peter on this, I strongly suspect he would be an ally of trans people – those most brave among us, who choose to be true to themselves in a world that sometimes makes it feel impossible to do so.

An innocent man had his freedom taken from him, his name inextricably linked to society’s most vile crime, dying at 61 before his name was restored. And yet against the greatest adversity, Peter somehow navigated his life with grace and gentleness. My hope is that we can move forward in the same way.