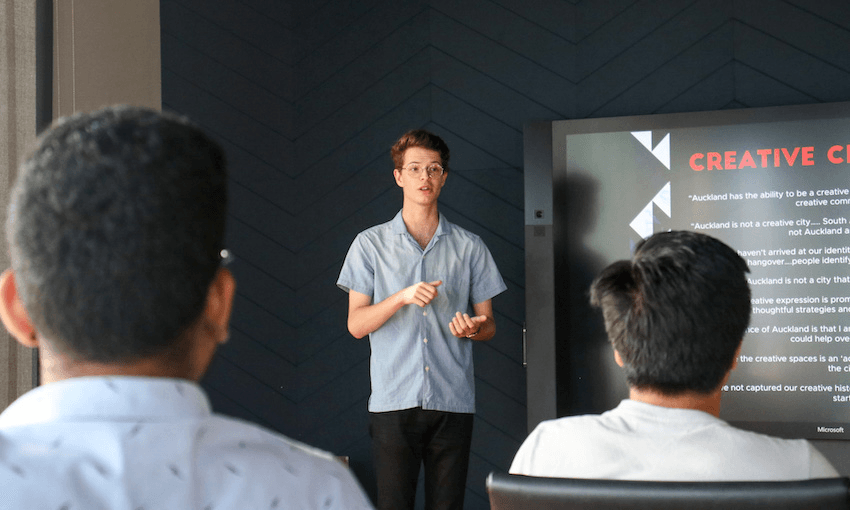

Sam Brooks talks to Matthew Goldsworthy, the 20-year-old founder and CEO of Youth Arts New Zealand, about helping young people access the arts both as creatives and as an audience.

What’s the point of having a vibrant, robust arts culture if the next generation can’t access it? The old adage of “it’s not what you know, but who you know” is true in pretty much every industry, but in the arts, there’s an organisation trying to change all that.

Youth Arts New Zealand (YANZ) is a social enterprise that connects, develops and showcases creative young New Zealanders. Founded by 20-year-old Matthew Goldsworthy, the organisation is a youth-led registered charitable trust that aims to become a launchpad for young people to access the arts both as creatives and as an audience.

Its projects include Te Kahui, a creative writing programme in Mt Eden Corrections Facility for young inmates, and Summer at 38 Hurstmere, a collection of 15 events that showcase young creatives in partnership with placemaking agency Fresh Concept. Its future events will feature monthly connection events across the country designed to mix networking and education.

YANZ started as a self-funded non-profit three years ago and now it’s ready to take the next step. Pre-Covid, the organisation would make ends meet through live events, but that source of revenue had dried up by the time lockdown came around. In order to cover its core costs and fulfil its mission, it started a Boosted campaign which ends on Friday, June 12.

In high school, Goldsworthy was passionate about music in high school, but his alma mater (Northcote College) didn’t offer a huge range of creative opportunities for him and his peers. As a result, he started an arts council and an annual arts showcase, and after he graduated, he started an event called The Thing About Music which brought together over 20 musicians from the North Shore to collaborate, create and perform to members of the community. Out of this kind of entrepreneurship, YANZ was born.

“What we’re working on is essentially how to develop a national organisation that can support young people in their creative endeavours,” says Goldsworthy. “The two things that underpin that are the financial side of things, and the social side of things. A lot of the work that we focus on is around providing creative opportunities that are paid so that it feeds into that financial side and provides young people with an opportunity to extend their portfolio. It’s really, really difficult for people to find or latch onto opportunities that can expand that portfolio.”

When Goldsworthy went to London, he started to draw parallels between the arts industry in the UK and the industry back home. He found the biggest difference had to do with the overall infrastructure that led to successful, long term, creative careers. “You have to have social infrastructure in place. You have to have people that are accepting of creativity. You have to have businesses that are encouraging creative thinking and practices, and people growing up in communities that value and celebrate the arts.”

“A big part of the work [that’s being done in the UK] isn’t necessarily on how they can capitalize on that [infrastructure] but identifying where the opportunities are with communities that aren’t so opportunity-rich, and how creative opportunities can have financial and social implications for those communities.”

However, while a lot of funding in the UK seems to pool straight into London, Creative New Zealand has made efforts recently to funnel funding into the regions. Last year they announced the Ngā Toi ā Rohe – Arts in the Regions Fund which was set to launch in March 2020. But like every discretionary Creative New Zealand fund, it was derailed by Covid-19.

Luckily, one of the advantages of the arts industry is that can a lot of experiences be delivered digitally, whether in the form of streamed shows or collaborative remote working.

“There are a lot of digital opportunities that we’re facilitating and those have no regional limits, so it’s really exciting to be able to provide those creative opportunities to people that don’t necessarily need to be in the Auckland CBD or something.”

But there’s still the problem of lack of access to the arts. For many creatives, success can come down to who you went to school with, who taught you, and the connections you form in tertiary learning more so than what you bring to your specific art form. In the hierarchy of “who, what, where, and how”, “who” still very much sits at the top.

Goldsworthy says an important part of addressing the issue comes down to increasing exposure to the arts. As a musician, he was able to access the arts through his parents exposing him to music. From there, he grew to love film scores and started to form an understanding of what he wanted to make as an artist himself.

“I think it’s just ensuring the arts is embedded within our culture. I went to Europe last year and I saw how alive it was with creativity. There are dance classes happening by the riverside, public buskers everywhere without permits. All these things completely elevated those cities.”

“Too many times I’ve heard people saying that we don’t have the right structure, that being an artist just isn’t a suitable career and you just have to know people and know how to do it. What we’re doing is saying we can step in and help out.”

You can find the Boosted campaign for Youth Arts New Zealand right here.