For more than 100 years, the Townsend telescope stood pointed at the sky from Christchurch’s Arts Centre. Then the earthquake hit.

Taken in the days following the catastrophic Christchurch quake in 2011, there’s a photo of astronomy professor and director of Mt John Observatory Karen Pollard in a hardhat and high vis, peering gingerly into a pile of jagged steel poles, wooden planks and crumbled stone at the Arts Centre. “All the scaffolding was munched,” recalls Pollard. “And the observatory dome was completely flattened and in pieces.” What she was more interested in, however, was not the dome itself, but something that had resided inside it for well over 100 years.

“We looked through as much of the rubble as we could, but it just didn’t seem to be anywhere. That became the big question – where is the telescope?”

The story of the Townsend Teece telescope begins a century and a half prior. Made in England in 1864, the telescope arrived in New Zealand some time in the late 1800s to observe the once-in-two-centuries transit of Venus in 1882. It was owned by local astronomer James Townsend, who eventually donated it to Canterbury College upon his retirement. The Christchurch Astronomical Society scraped together £420 to build an observatory tower on campus with a plan to open it up to the general public (The Canterbury College campus would later move to Ilam, leaving the site we now know as the Arts Centre).

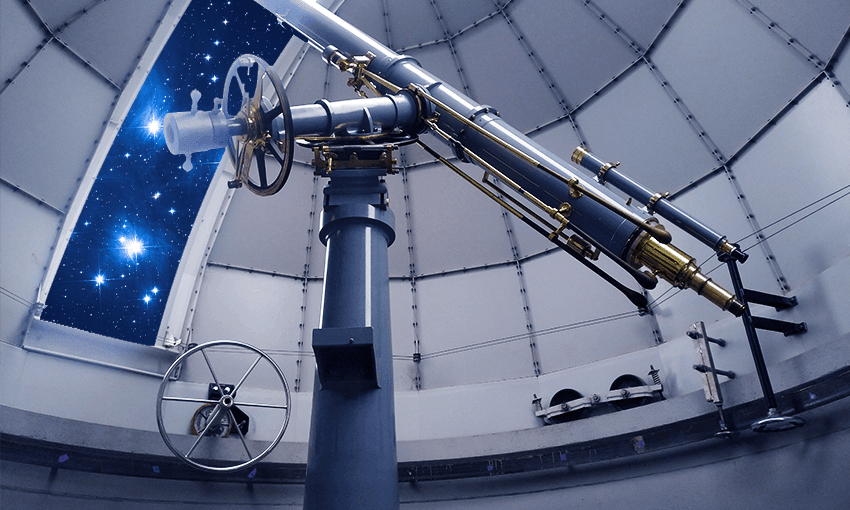

Opening to the public for stargazing sessions in 1896, the observatory became the place to be on Friday nights in Christchurch. Pollard references an article from The Star in 1899, in which a journalist gazes at the Kappa Crucis “Jewel Box” cluster through the Townsend. “Seen through the telescope, it appeared as if the most brilliant sapphires and rubies, with diamonds of the first water, had been scattered with lavish hand over the field of view,” they wrote. “One learns something of the movements of the heavenly bodies, and something too of the depths of the universe.”

The Townsend telescope remained an important Christchurch feature throughout the 1900s, going through a refurbishment in the late 1970s. The lead technician of the telescope revamp, Graeme Kershaw, fostered a particularly close relationship with the Townsend – his first job as a teenager in the University of Canterbury mechanical workshop was to build a new lens cap for it. “He would go on to maintain that telescope for the next 50 years,” says Pollard. “It was a bit of a pet project because he always felt quite a connection with the Townsend.”

That connection was put to the test in 2011 when the devastating 6.3 magnitude earthquake struck Christchurch, leading to a significant loss of life and widespread damage in the central and eastern suburbs. The Arts Centre observatory had already been cracked and weakened by the 7.4 magnitude quake six months prior, and was covered in scaffolding when the next quake hit. Due to safety risk, the Townsend was unable to be removed before February 22, 2011, meaning it came crashing down with the entire observatory dome.

“When the February quake struck, the tower completely pulled away from the building and fell down,” Pollard recalls. “Of course, I didn’t know that for a couple of days.” It was only when she received some photos from a colleague involved in Urban Search and Rescue (USAR) that she was able to see the true extent of the damage to the Arts Centre. “I was absolutely horrified, but I could see that the observatory dome was still intact, and the scaffolding was sitting straight on the ground, possibly cushioning the fall of the telescope.”

Not long after, USAR entered the premises to look for any people who might be under the rubble, trawling over and through the remnants of the observatory with a digger. “We were eventually allowed in wearing hard hats to sort through the rubble, but all that they had found of the telescope was the plinth that it sits on.” Pollard began ringing around scrap metal yards, Christchurch council and USAR, on a desperate hunt to find the telescope. “This is a big tube, you know, it’s not hard to miss. It’s big, it’s brass and it’s eight feet long.”

Finally, there was a breakthrough. The Arts Centre found the telescope stashed away in a nearby building. “Someone, we still don’t know who, had gone through the rubble and collected up all the little pieces – all the tiny little screws, all the money from the donation box,” says Pollard. “We had virtually everything apart from a few minor things missing. It was very badly damaged, but it was all there.” The now “munched” Townsend telescope was delivered by truck to Graeme Kershaw, who got to work cataloguing all the gnarled and flattened pieces.

“It looked like a disaster,” says Pollard. “I just couldn’t believe it.” Although it looked like “a big pile of junk” there was another miracle to be discovered. Kershaw gently removed the lens cap – the very same one he built as his first job in 1966 – to find that the six inch lens, first installed 165 years prior, was still completely intact. “He just came running over to me saying ‘the lens is intact! The lens is intact’,” laughs Pollard. “We were totally overjoyed because the lens really is what defines the telescope, we call it the heart of the telescope.”

After a few years of fundraising, which included a substantial donation from US-based New Zealand economist David Teece (hence Townsend Teece), Kershaw began the restoration of the telescope in his garage in 2016. “He had just retired after 50 years in the department of physics, but then got straight to work restoring the telescope, straightening bits out, and reproducing parts where needed,” says Pollard. “He was always the one who really pushed for the restoration and always said that the telescope belonged to the people of Christchurch and it had to be restored for them.”

While he was nearing the end of the restoration project, Kershaw suddenly fell seriously ill and passed away unexpectedly in May 2018. “We’d only just taken the telescope with us to a conference because he’d nearly completed it, and within a couple of weeks he had died.” Kershaw’s funeral was held in the Great Hall of the Arts Centre, right across the courtyard from where the Townsend had sat, pointing skyward, for over a century. “It was a shock for everyone,” says Pollard. “And, as you can imagine, it put a spanner in the works for some time.”

Kershaw’s wife Dale continued to work on the sanding and repainting of the plinth, and another technician, Quintin Rowe, was brought in to finish off gears that allow the telescope to move. Pollard recalls “lots of emotions” when it was finally reinstated at its home in the Arts Centre earlier this year. “When we opened it up and the telescope was in place, it was just beautiful,” she says. “This is something that was made in 1864 by hand and, when you look through it, you see the same things that people were seeing 127 years ago, from exactly the same site.”

Every Friday night in winter, astronomy students from the University of Canterbury take small groups up to the observatory tower for stargazing sessions with the Townsend Teece until 10pm. On a clear night, members of the public can see Saturn’s rings, the craters and mountains on the moon, the swirling equator of Jupiter, and maybe even the same sapphires and rubies observed by The Star back in 1899. “It was such a relief that we finally got it done. So very proud, so very relieved, so extremely happy,” says Pollard.

The open nights have also provided a place for people to share their memories of visiting the Townsend as a child, perhaps with their parents or grandparents, to reflect on those who may no longer be here, or to simply quietly ponder their place in the universe under the twinkling night sky. “Doing these open nights has made me realise how much the people of Christchurch really appreciate it. I think the whole story, not just of the restoration, but of the telescope too, links it so deeply to the history of Christchurch itself,” Pollard says.

“It really is a miracle that it got through the earthquake intact, and I think it will always have a soft spot in many people’s hearts.”