In week five of another lockdown, Anna Rawhiti-Connell heads back to the safety of her 20s.

On the night of my 42nd birthday, the second lockdown birthday of my 40s – a decade reclaimed as “the best of your life” by the crushing weight of societal expectation that life simply must keep getting better – I fired up my 42nd lockdown listen of the Best of Lilith Fair and contemplated whether Meredith Brooks, the raven-haired songstress of the 90s, was a songwriting genius.

“I hate the world today” is the opening line to her best, and kind of only, known song ‘Bitch’. It’s a lyric for our times.

Fuelled by the power of more messages than usual because I’d advertised my birthday on Twitter as a form of emotional insurance, I danced in my lounge, belting out and slipping into the lines of the song to become the simple tropes of what it meant to be a woman in the 90s and early 2000s. Complicated but easily defined. Layered but not yet dissected into nanoparticles by years of internet commentary. Comfortable in the fading light of second wave feminism, and still shielded from the righteous yet confronting questions posed by the fracturing of identity that seems to define the current times.

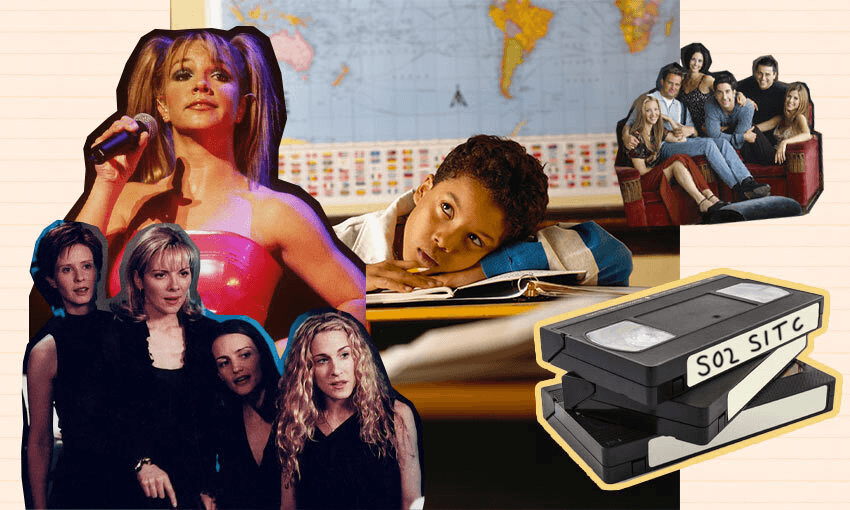

“I’m a bitch,” I sang. A mother (to a dog). I was a child, I am a lover (although less so during a government-mandated staycation) and I’m a sinner, biblically, many times over. I’m also a saint, quite specifically at this point in the current lockdown, having not yet told my husband to “not be in my sightline for as many consecutive hours as possible”. I’ve been finding a lot of comfort during lockdown in soothing sound baths of music from Brooks and her contemporaries, with a generous helping of long, absentminded watch parties (just me) of late 90s and early 2000s TV shows like The Secret Life of Us and Sex and the City.

Seeking comfort via trips down memory lane during lockdowns is not unusual. Pandemic related consumption of nostalgia is now a well-researched phenomenon. Kirsty Ross, a clinical psychologist and lecturer at Massey University, assures me that it’s fine. Even sensible, up to a point. “We encode memories as feelings,” she says. Sensory experiences like listening to music or baking certain foods will evoke an emotional response based on remembering a certain time.

“It’s not unusual to seek out things which evoke positive emotional responses. It’s a really understandable and sensible thing to be able to do. We do things to try and create some stability and predictability. So we might read a book that we’ve read three times because we know how it’s going to end.”

But why am I stuck in a constant repeating loop of it, more so now than during any previous lockdowns? It’s as if this lockdown, the fifth for Auckland and now the longest to date, has me holding onto decaying totems of identity that I thought I’d left behind.

In her new single, ‘Mood Ring’, a song from this millennium that has managed to penetrate my seemingly impenetrable Fortress Nostalgia, Lorde asks “Don’t you think the early 2000s seem so far away?” Yes, my god, Ella Yelich-O’Connor, they do, but I am hauling them back to me at a feverish pace. Because unlike 2020, when I thought perhaps we’d “go back to normal”, it’s very clear the mark left by the pandemic will be indelible, and the world forever changed.

“I think that’s part of a grief process,” says Ross. “There’s a lot of people who have a feeling that there’s going to be BC and AC, before Covid and after Covid, and there’s a sense of anxiety and uncertainty about what exactly we have lost and how long have we lost it for?”

I tell her I’m concerned that I’m burying my head in the sand by constantly cycling through shows that I know aren’t really fit for purpose any more and returning to music that might still stand the test of time but takes me back to a place when my outlook was less evolved. Artefacts that perpetuate negative stereotypes so many people have worked hard to rail against, and yet I find comfort in their simplicity. I feel I’ve somehow gone soft and am hiding from reality at a time when we need the fortitude to face what lies ahead.

Ross agrees that when we overuse something, any coping strategy, it tends to become maladaptive. “We encourage people to have a toolbox of strategies and not overuse one or two,” she says. Noted. Nicholas Holm, senior lecturer in media studies at Massey University, points out that this trend towards the nostalgic, while exacerbated by the pandemic, was well under way before Covid hit. “In 2019, Friends was the most popular streaming show in the world and subject of massive bidding wars between different streaming services,” he says. “It’s really amplified by the digital platforms used to consume culture these days. Netflix and Disney+ don’t really distinguish between the old and the new, in the way the old media platforms and channels would have.”

Coming in like a circa 2013 wrecking ball to my concerns about nostalgia – and its possibly unhelpful and false vestiges of safety – is a comment he makes about what else the 90s and 2000s were. “The 90s and early 2000s really were the last gasps of a monoculture, of the idea that we had a set of cultural texts that we all were familiar with.” This revelation clangs loudly in my head. It clangs like the episodes of Sex and the City that briefly featured the trans community in the rapidly gentrifying Meatpacking District in Manhattan. It clangs like the fat suit episodes of Friends and like the simplistic divisions of women into smart yet scorned and pretty but empty, melodically strummed out, in so many of the songs I loved in my 20s.

I realise that I am not clinging to my 20s because they were a personal golden era when I had less responsibility and was wholly occupied by whether I could borrow the one pink boob tube we shared among my group of friends for a Friday night at the Outback. I am simply nostalgic for the monoculture. For a lack of fragmentation, a simplicity of ideas and unified regulation of what was right and wrong. It’s a false comfort.

I recognise that, perhaps even without the pandemic, the yearning for a simpler time is about the loss of singular cultural totems as a way of navigating the world. But I don’t want to return to that time, because the shattering of those totems led to trans people owning their narratives, the renaissance and reclamation of te reo Māori, and today’s young people not feeling bound by the restrictive gender tropes and norms the way my generation did in the late 90s and early 2000s.

I may be a bitch, a child, and a lover. But I know better now, and that’s a good thing.

And when lockdown ends, this bubble of safety will be the first one I puncture.