To mark the release of a new online film about intelligence agencies and privacy, seven New Zealand artists reflect on self-censorship in the surveillance age.

As many as 11% of Yahoo Chat conversations involve naked participants. That is what British surveillance agency GCHQ discovered while testing their surveillance powers in the operation “Optic Nerve”.

While this statistic is (maybe) enough to keep your clothes on, there are bigger implications for our society when we know we are being watched. Indeed, newer allegations have arisen that Yahoo Inc created software to search its users’ inbound emails for US intelligence officials. Who wouldn’t check themselves before they wreck themselves, under these circumstances? But while self censoring may be good in some settings, it can also stop the advancement of new ideas. This has a name: the chilling effect.

Last week the online film I Spy (With My Five Eyes) arrived on the internet. The NZ-Canada co-production explores the tensions between governments, intelligence agencies and individuals as data collection grows and personal privacy is eroded. In it, Katy Bass from PEN America talks about a PEN study of 800 writers worldwide, which found that concern about surveillance is nearly as high among writers living in democracies as those living under authoritarian regimes.

One in six of the writers surveyed were “avoiding writing or speaking about certain topics”, says Bass, because they were worried about government surveillance, while one in four were “starting to curtail their use of social media”.

The I Spy producers asked several New Zealand artists whether they modify their artistic output in the face of ever-growing data collection. Their responses are below.

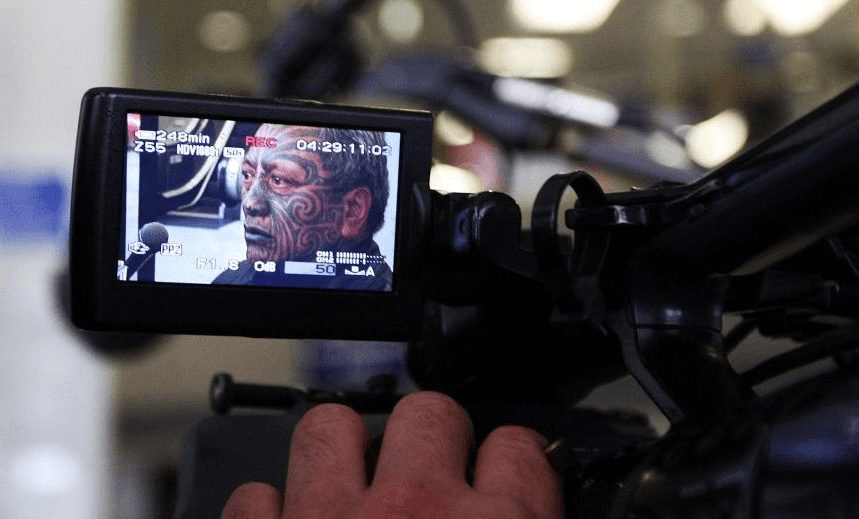

Tame Iti (Ngai Tuhoe / Waikato / Te Arawa), artist and activist

I think it would be fair to say that I have never been known for censoring what I think about things. When you are trying to create a consciousness about murder, land confiscation and injustices that go back 170 years, censoring yourself seems like the opposite of what you should do. As we approach the ninth anniversary of the October Raids I am acutely aware of the reality of state surveillance based on your political views and after the raids I was given “time” to consider several things. Uncensored political expression through art and the disruption of a narrative through media and social media.

As I get older, expressing myself through painting is what I like to do the most. The theatrical art form people are used to seeing from me is best performed by the young. With the help of my sons, I have learned new ways to get my message out there. Through public speaking and social media I am now able to express my views undistorted (and uncensored) by the media.

What is my message? … Well … my message has not really changed, it is the reason I have never thought to censor myself or give in to the fear … The message, is best summed up with this proverb:

Ka warea te ware

Ka area te Ranatira

Honihoni te whewheia

Honihoni te manehurani

Kei au te Ranatiratana

Ignorance is the oppressor

Vigilance is the liberator

Know the enemy

Know the destiny

Determine our own Destiny

Jessica Hansell, aka Coco Solid, musician, artist, writer, creator of Aroha Bridge

For me disclosure and transparency is not a fixed ethos I have. It depends on what I need, I use digital media as a platform but as an outreach too, a way to document both my internal life and my external happenings. Sometimes there will be things I want to share that could have professional or social consequences for my survival, so I choose to be a diplomatic, abstract or reductive about it. Sometimes I will be the opposite of that to prove a point – I’m allowed to say and feel whatever I want.

Do you trust your government to protect your information and protect your rights to create whatever you want to?

Not really. Jenny Holzer styles, abuse of power comes as no surprise.

David Farrier, journalist, director (with Dylan Reeve) of Tickled

I thought a bit about my policy on self censorship after watching the utterly pointless Snowden, Hollywood’s take on Citizen Four, which did everything Snowden did but better, and was, you know, real. Although maybe it’s not a pointless film as it got drongos like me thinking about it again.

Anyway, my policy so far in life has been to not self censor. It’s perhaps a fairly flawed stance after revelations of mass surveillance and the collection of metadata and all that – but even with this in mind I still find it hard to break away from, “If you haven’t got anything to do hide, who cares”.

Yes, I know all these tiny bits of information the government knows about me could be swung to illustrate whatever elaborate case they are coming up with against me, but honestly, I just worry about other things. Did I leave the tap on. Will I get hit by a bus. When am I going to get a clot in my brain and drop dead, my body left alone in my apartment to rot, only to be discovered weeks, possibly months later.

I don’t trust the government (Hey, I grew up on The X-Files) but if they want to snoop on me, go ahead. Print my emails on the front of the Herald. I just don’t care as far as my own life goes. As for what it means to the rest of the world in general – yes, it’s terrifying.

Jaquie Brown, broadcaster, writer, comedian, author

I have an interesting relationship with privacy. I am fine to have it compromised when I’m in the steam room at the gym, I don’t mind prying eyes at all. Maybe I feel protected by all that steam, maybe I’m an exhibitionist – who really knows.

But when it comes to signing up for store discounts and giving my information away I am extremely mistrusting. I would be happy to miss out on a 30% discount on toothpaste at the supermarket just to keep my information to myself. I don’t want people knowing what I buy, where I shop, my star sign (probably irrelevant: Libra).

I swing between trusting nobody then thinking I’m over thinking and trusting everyone and then watching Mr Robot and trusting nobody again.

It’s a great way to live.

Leila Adu, composer currently based in NYC, recently released the EP Love Cells

As an artist and human, my heart/mind are conjoined with social issues of climate change, pacifism and equality for all. I’m a NZ and British citizen, and I feel free to express my political views in those places. However, I realized that as an immigrant to the US, I began to feel that I could not express my views around police violence and racial inequality in prison sentencing and, fatally, the death penalty. And, as a person of colour, I feel especially vulnerable.

Before my citizenship was confirmed, I released a song online under a pseudonym (lamenting the murder of a man on death row, whose witnesses had retracted their statements, stating that the police had forced them to make the statements). Of course this wasn’t encrypted or anything, it’s not an example of safe practice but it is an example of fear.

As soon as I heard about the Snowden leaks, I had the distinct feeling that every email, every chat, and eventually, every phone call, could be watched. I am not involved in illegal activity, so what was my reason to be worried? I guess it’s because I know a enough history to know that political regimes and laws can change. What is OK today, may not be OK tomorrow. If you were a compassionate and intelligent person in the Nazi era, or any dictatorship regime, like under the KGB, you could be watched, and logical and compassionate actions would become illegal. People thought I was paranoid. Now Donald Trump is running for president. Was I paranoid?

I basically don’t publicly share – email, write, or share on social media – anything that I would not want to be published. Some things that I share online may be a problem in some nightmare future, but they are things that I believe in and would stand behind.

Marianne Elliott, director of ActionStation, author of Zen Under Fire, human rights lawyer, owner of La Boca Loca

Do I censor myself in my writing and social media sharing? Yes, absolutely. Primarily because I don’t want my personal opinions to be misconstrued as the political or policy positions of the organisations where I work. But I’m also very aware of the prevalence of governmental and inter-governmental data collection – not least because of the time I spent living and working in the Gaza Strip.

Does this have a chilling effect on what I write? I’d like to think it doesn’t, but the reality is that every time I stand in line at US immigration I find myself wondering if they’ve read what I wrote about the US role in Pakistan yet, or something along those lines. Over time, those nervous moments add up, and it would take a stronger person than me to be sure that their writing was entirely unaffected by them.

Paula Morris, author, convenor of the Academy of New Zealand Literature

I always censor what I write on social media because it’s public, not specifically because of government surveillance fears. Anything you publish can be used for or against you, whether it’s in a book or on the internet.

I don’t know that it’s worse now than in earlier times; artists creating subversive work have often found themselves in trouble, or at least under scrutiny. How is the work subversive if it doesn’t undermine or question authority in some way? Anyway, there’s a difference between making pronouncements on Twitter and making art.

I Spy (With My 5 Eyes) is a New Zealand-Canadian co-production financed by NZ On Air and Canada Media Fund. It was created and directed by Justin Pemberton (The Nuclear Comeback, Chasing Great) and produced by Carthew Neal of Fumes (Tickled, Hunt for the Wilderpeople)