Abused as a 12-year-old, David Hill’s circumstances were different from many of those now telling their stories to the Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, but his sense of confusion and shame was the same – as was his urge to stay silent for years.

This article contains references to sexual abuse. Please take care.

They were talking about the Abuse in Care inquiry. “This sexual abuse business is a real industry,” said Voice One. Voices Two and Three chimed in: “Uncle pats you on the bottom when you’re three, your life’s ruined… Political correctness…”

I could have said something, but didn’t. Braver voices did speak up: “Hang on, eh?….There’s some shocking cases.”

Why could – should – I have spoken? Because I was sexually abused as a kid. If you haven’t already rolled your eyes and headed off, I’ll give you the details.

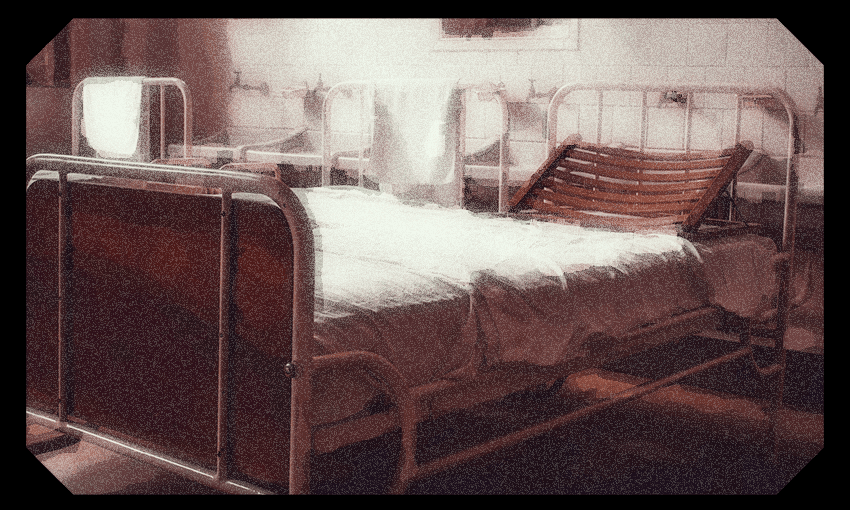

I was 12. I ended up in hospital because a cricket ball had impacted my left eye, and I spent ten days in a ward full of other damaged male eyes, all adult except for me.

For some 1950s reason, we weren’t supposed to move around. Maybe they worried we’d walk into doorways. So a male orderly wheeled us everywhere.

The orderly (I’ll call him B), was in his 40s-50s, brimming with bonhomie. Every time he entered, he’d josh patients into grins and laughter.

I’d been hit by a cricket ball? That must have stumped me? Bowled me over? Silly stuff, but I felt flattered to be acknowledged by a grownup. It was, I realised years later, the first stage in grooming.

A couple of days after my admission, B wheeled one of the others back into the ward, then walked across, sat on the edge of my bed, and began talking to me. I was surprised, but again, I felt flattered.

Two minutes, and his hand was on the bedclothes covering my knees. I can’t recall how I felt about that. Another minute, and the hand was paddling at my groin.

I was frightened; I do know that. And bewildered. I knew nothing about sexual molestation or paedophiles; the words weren’t in my or my parents’ vocabularies.

It set the pattern for my remaining days in hospital. B would enter the ward, and my stomach would knot. He’d joke with the others; sit on my bed; fumble more and more insistently at my crutch, his body turned so nobody else could see what he was doing.

I’d try to push his hand away, keeping my own movements as small as possible, because I didn’t want anyone else to know what was happening. He’d already made me complicit, established a secret between us.

A couple of times, I protested: “Cut it out.” But B was an expert at this, and his reply came instantly: “I’ll cut them both out.” Somehow, that drew me further into apparent acquiescence.

Once, he told me what I now recognise as a fabricated story about how at dinner, his teenage son would describe how he and his girlfriend fondled each other. “Natural to talk about it, eh?” It was all part of the grooming.

So, the question. Why didn’t I tell anyone?

Tell whom? The doctors were remote and Olympian. The nurses were all young women, and for a gauche male pubescent to describe B’s actions, mention the body parts involved, was unthinkable. My parents? Equally unthinkable.

The other guys in the ward? But they were all adults, remember. I’m sure B never tried anything with any of them. I was a child, lacking any power or authority.

And anyway, I felt soiled, grubby. As I say, B had made me an accomplice. To tell anyone meant admitting I’d taken part in what happened. And maybe there was some whiff of depravity about me that attracted him. It was a classic course of manipulation on his part.

It lasted till I was discharged. I developed a stammer for a year, but otherwise I was “unharmed”. Except that I never told anyone, parents or friends or partner, till half a century later, when the guiltlessness of the victim in such cases had become an accepted fact.

Even then, as a man who’d worked with words, ideas, stories for a long time, I heard my voice start to catch and stumble. I couldn’t look at my wonderfully supportive wife or the good friends who were listening. At the end, I heard myself swallow, gulp, knew I should have spoken out far, far earlier.

Long before then, one other event helped. Two years after I left hospital, B’s name was in the paper. He’d started molesting another patient “a youth”. But this time, he’d come up against someone brave. The victim complained, and in the late-ish 1950s, what courage that must have taken.

B was tried, convicted, sentenced. I read the reports surreptitiously, and realised I hadn’t been the only one; I hadn’t exuded any special air of decadence. I took deep breaths and a miasma seemed to lift from me.

I should have spoken up when I heard those comments of my opening paragraphs. I should have said that such abuse is ubiquitous, that a protected white male can be a target, too, that for victims to come forward is an act of courage, not any sort of self-promotion. I didn’t, so this is my belated attempt at compensation.