I only started studying te reo at Te Ataarangi this year, but I knew straight away that there was something different about it – and not just the fact that we use cuisenaire rods instead of pen and paper, writes Nadine Millar.

Shame is one of the biggest barriers many of us face in learning Māori. The word whakamā means “to whiten” yet it’s so much weightier than that. Shame and fear of speaking Māori isn’t something that only affects shy people. Even the most confident speakers can lose their voice sometimes. I’ve heard people deliver powerful prepared whaikōrero, or recite karakia beautifully, only to see them clam up and stumble when the formalities are over and conversations around the table take on a casual tone.

The worst part is, they’re often criticised for it. Whispering behind cupped hands, people say things like, “he’s fluent on the paepae, but he can’t ask for a cup of tea.” It’s little wonder we’re scared to open our mouths. Not only did we inherit the fear of speaking from our ancestors, many of whom were beaten or made to feel stupid for using their native tongue, but often, we put each other down as well.

This isn’t an attitude you’ll find in a Te Ataarangi class. In fact, the first thing you learn as a student of Te Ataarangi is that upholding each other’s mana is paramount. The five governing rules of Te Ataarangi intrinsically recognise that for many of us, the hurdles we face are emotional rather than intellectual, and that the people around us can either magnify those hurdles or help us overcome them.

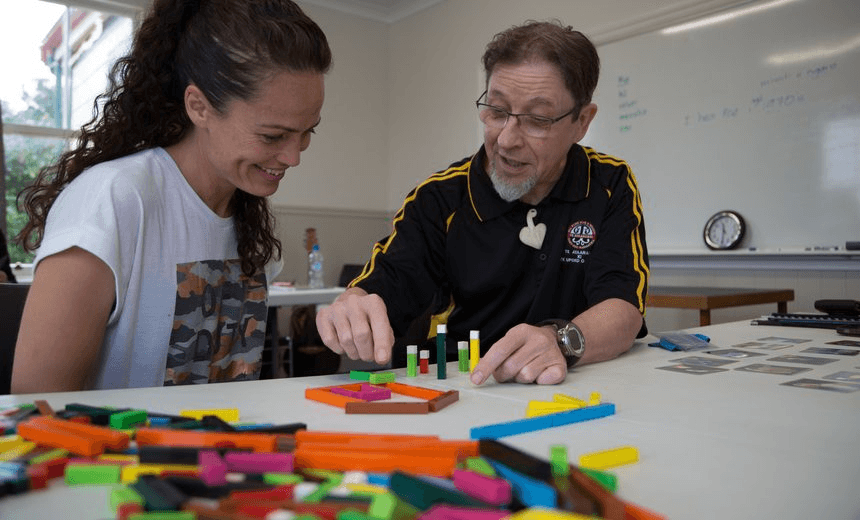

I only started Te Ataarangi this year, but I knew straight away that there was something different about its approach – and it wasn’t just the fact that we use rākau (cuisenaire rods) to learn instead of pen and paper. My teacher, Te Atakohu O’Sullivan, says one of the first lessons people learn in her class is to see with their ears and hear with their eyes. It’s about using all your senses to learn.

Students watch how the rākau are laid down and follow along, creating pictures and describing what we see. More complex sentences evolve over time as each learner’s skill improves. It’s a great way of demystifying some of the language structures that simply don’t exist in English, because the ambition is not to translate Pākehā sentences into Māori, but to unlock language in our subconscious mind. More importantly, Te Ataarangi aims to get people speaking from day one.

Te Ataarangi is different in other ways, too. It emphasises group learning over individual assessment, recognising that “ako” encompasses both teaching and learning. In other words, the basis of learning is partnership, not testing. Ruakere Hond, Chair of Te Runanga o Te Ataarangi, told me that for Māori, learning Māori is so closely aligned to our identity and our hopes for our own children that we often put too much pressure on ourselves. “There are so many emotions people go through while they’re learning. The idea with Te Ataarangi is to try and limit the fear and get the group to work together.”

When the basis of learning is partnership, it’s natural that your classmates begin to feel like whānau – which is why there’s always an annual get together. This year’s Te Ataarangi Hui Whānui was hosted by my rohe, Te Ataarangi ki Te Upoko o Te Ika (lower North Island). It was held at Takapūwahia marae, just down the road from me.

I put down my name to help and was assigned the role of photographer. It was a job that gave me a bird’s eye view of everything happening across the weekend – from the kaimahi working to cater for the manuhiri, to the Māori wardens directing traffic in the bitter cold, to the many and varied workshops for the manuhiri.

The theme for this year’s Hui Whānui was “hoki mai ki te orokohanga” – returning to the beginnings of Te Ataarangi. On the first night, after dinner, kuia and koroua stood to share their memories of the first Te Ataarangi teachers in their rohe. Almost all those early teachers were native speakers. They recognised that revitalisation of the language needed to happen in the community and within our homes rather than in schools and universities. It’s a philosophy that still guides Te Ataarangi today. There’s a place for formal instruction, but unless people are able to use Māori outside the classroom, within our whānau and communities, the survival of our language will always be under threat.

Dame Te Heikōkō Katerina Mataira and Te Kumeroa Ngoingoi Pewhairangi developed Te Ataarangi in the 1970s. For many people, especially Coasties, Katerina and Ngoi are household names. Katerina was an author, artist and academic. Ngoi was a prolific composer with hundreds of songs to her name – best known among them E Ipo and Poi E. Of Ngāti Porou whakapapa, both Ngoi and Katerina were at the forefront of the Māori revitalisation movement and instrumental in the development of many of the institutions we now take for granted: kōhanga reo, kura kaupapa and of course, Te Ataarangi.

Together, Ngoi and Katerina travelled the country, finding native speakers and training them to become teachers. There are now hundreds of classes around the country across 10 regions, plus whānau in Australia. When Ngoi passed away, carver Greg Whakataka Brightwell presented the Te Ataarangi whānau with a waka huia. This is a beautiful treasure box adorned with Ngāti Porou tūpuna and it now journeys around the country, just as Ngoi and Katerina did, continuing their work to celebrate te reo Māori and ensure that it will never be lost.

By the end of the weekend, I’d taken over a thousand photos. Going through them on Sunday night, I was struck by a few things. The first is that it’s impossible to tell who among us can speak Māori just by looking at picture. I seem to need to remind myself of it again and again. Perhaps it’s to do with of my own insecurities. I worry sometimes I’m not “Māori enough” or “Māori in the right way”. But it doesn’t matter what you look like, or where you come from. If you want to speak Māori, Te Ataarangi will teach you – ahakoa no hea, ahakoa ko wai.

More to the point, we need to challenge the common misconception that being Māori is a pre-requisite for speaking Māori. There are fluent Pākehā speakers among us – always have been. That’s why there was such a diverse group of people at the Hui Whānui. This is the kind of New Zealand I want to live in. A country in which diversity doesn’t just mean “we invited one Māori, one Pasifika and one woman to our panel”. But a country where Pākehā are just as comfortable walking in a Māori world as Māori have had to become walking in a Pākehā world. Not “becoming one people” but living side by side as equals, celebrating the things that make our cultures unique.

The other observation I made was how much laughter dominated the weekend. And I don’t just mean people smiled, I mean, people laughed so hard the photos were all blurry. Inside the tent watching the groups present their skits on stage, we laughed so much I thought we were going to shake the pegs out of the ground. The performances ranged from complex storylines with advanced language to simple ditties accompanied by actions. It didn’t really matter what the skits were or how polished they were, all that mattered was that we celebrated what people had to offer.

It made me realise that perfection is not only impossible, but kind of irrelevant. Enjoying the journey is a better goal than never making a mistake. Knowing more words and phrases next year than we knew last year, is a better goal than fluency. Feeling confident to try, and supporting others to try, is a better goal than being the best. Because it may well be that the best antidote to the shame and fear that creeps up on us, is a little bit of laughter.

The last photos I took were of the poroporaki, the farewell. It was the only time the mood in the tent became sombre. Karakia was offered and tears began to flow. Whānau from Te Ataarangi ki Taranaki, hosts of next year’s Hui Whānui, came forward to lift the taonga in preparation for her next journey. A soft lament floated through the tent as the taonga made her way out into the light, leading the way for the next generation of reo Māori speakers to follow.

The Society section is sponsored by AUT. As a contemporary university we’re focused on providing exceptional learning experiences, developing impactful research and forging strong industry partnerships. Start your university journey with us today.