How can we help people realise they’ve made a mistake without falling into the ‘callout culture’ trap?

This post was originally published in Emily’s newsletter: Emily Writes Weekly. Subscribe here.

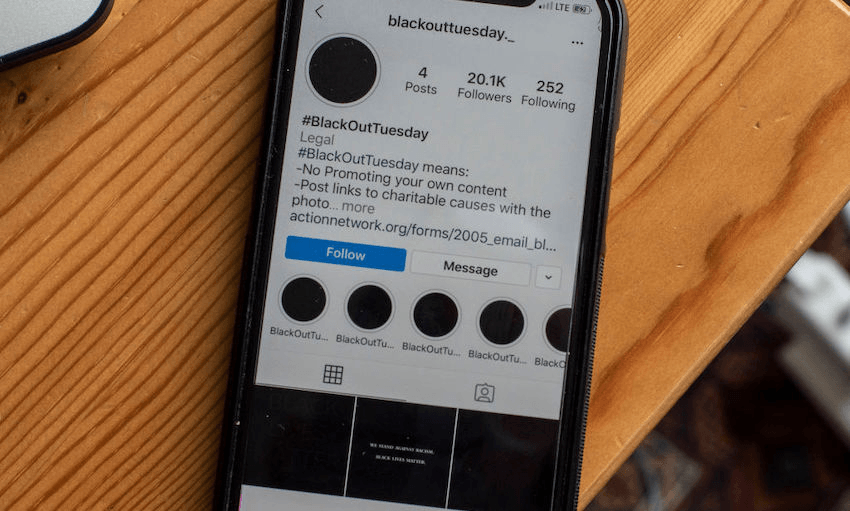

As soon as I saw the black squares on Instagram for Black Out Tuesday, I thought a feed covered in black squares would be helpful. I thought it would be a tangible sign that folk are listening and learning and encouraging others to do the same.

It was quickly explained to me that it was not helpful. The use of the hashtag was filling up and overtaking important information that was being shared about the Black Lives Matter movement and George Floyd protests. It was covering images of police brutality being witnessed and it was literally erasing black voices with black squares. I took the post down and then shared the same info with others. I then had a handful of people say variations of: I can’t do anything right! Am I better to do nothing? I was trying to help and now I’m being told off!

In these Covid-19 times I’m seeing this repeated when people are told they’ve shared false information. Some are upset because they’re “only trying to help”. Others have full-on meltdowns in their Instagram stories claiming they are victims of cancel culture because they have been told they need to be careful about what they’re sharing. We have seen how rumours spiral.

It got me thinking – why are we so afraid of being wrong? When we are children we know and expect we will be wrong sometimes. When learning to spell, we know if the teacher says it’s i before e, it’s not a personal attack. We get things wrong. We thank the person who taught us the right way. We get on with it.

Why, then, do we suddenly decide we are incapable of being wrong and that it’s a huge deal to be wrong? Why do we assume we’re “cancelled”? Why do people seem to want to be cancelled?

I’m wrong a lot. Being part of a community of activists, I’m used to being told when I make a misstep, when I fuck up, when I’m wrong. I view it as a kindness that someone cares enough to help me learn. Of course you want to avoid it because of the mahi involved in helping someone realise they’re not as right-on as they think they are. I’m not saying it’s a good thing that someone had to use their time to educate you. But it’s also inevitable that we will get some things wrong simply because we are learning.

Yet the mythical spectre of “call-out culture” means simply and gently correcting someone or supporting them in being a better ally turns interactions we used to consider basic into a hand-wringing mess, where those on the receiving end need to be nursed through online breakdowns. The amount of mahi involved in this mess seems to be increasing by the day.

“The Black Out Tuesday tag isn’t that helpful after all” or “that rumour you shared isn’t accurate and it’s also racist” becomes extreme online flagellation (“I am SO SORRY! I was just trying to help! I FEEL AWFUL”), which in turn puts the person supporting someone to be a better ally into the role of counsellor. Sometimes they’re met with not just fury from the person they tried to help, but fury from their friends too (“Babe! Fuck them! YOU DID NOTHING WRONG! You can’t do anything right these days! THIS IS CANCEL CULTURE!) It will then devolve into claims of bullying. And breathless Instagram stories saying “I would never cancel anyone” when nobody has been cancelled. It follows the same tired formula.

Again, it begs the question. What’s wrong with being wrong?

Clinical psychologist and senior lecturer at Massey University Kirsty Ross says being in a state of cognitive dissonance can be one of the reasons why some of us struggle so very much with being wrong.

“Cognitive dissonance is based on the idea that we like being consistent between our thoughts and beliefs and behaviours. If someone points out we are not being consistent, or we realise it for ourselves, then we can either change our behaviour, which is no small feat, or get into motivated reasoning. That’s where we basically shift our thinking and rationalise why our behaviour is OK. So, if you smoke, but you know that smoking can lead to cancer, there can be dissonance. You can then choose to stop smoking, which is difficult, or rationalise to yourself that the risk is low, it happens to other people, and if you eat healthily and exercise that will balance it out, and that helps you to feel OK about continuing to smoke.”

The framing of these conversations, which are almost always online, can also hinder the ability to listen and learn and sit in the uncomfortableness of being wrong. The most important part of learning and moving on from that uncomfortableness could be challenging due to the way we’re discussing things. Ross says people need to be given a chance to admit they are wrong and back down from their position with dignity. They need to see that mistakes are opportunities to learn, rather than failures.

In my view, it’s hard to gently guide someone through learning when that someone is an absolute punisher, but Ross knows that it works.

“If we feel attacked for a position we hold, we are then likely to defend that position, which means we will work hard to provide evidence for why we feel and think this way. The more we work to convince someone else of the validity of our opinion, we are actually convincing ourselves more as well, and we can become more embedded in our views,” she says.

This makes sense for deeply held opinions and beliefs we might have developed in childhood and carried through our whole lives, but what does it mean when sharing information about something quite simple becomes fraught? A quick message of “hey, I see you shared this thing and now we’re being told it’s not helpful” shouldn’t trigger a feeling of attack. Yet we are seeing that it does.

How we view ourselves and our ability to have our views challenged might be behind how we respond in these instances. Ross says it’s all about understanding growth mindset – mistakes are OK and getting things wrong isn’t a judgement on you as a person. Because you’re still learning.

“This [approach] creates room for learning with dignity. People can get quite black and white and all or nothing in their thinking – so either it was perfect or a failure, and ‘if I get it wrong, I’ll never know how to do it’. So they think that a mistake means they know nothing, which is distressing, or worse that they will never master this task or skill. So we need to teach people right from childhood that mistakes are part of learning, and they don’t reflect badly on you, they just mean you are not there yet.”

How can we make commitments to acknowledge we’re not there yet? When teaching my child maths I often get them wrong because quite simply I’m not good at maths. It makes sense to me that if I get those simple things wrong, of course I would get big things wrong too. Feeling it’s right to be wrong sometimes is crucial if we want to be better and do better. Being able to quickly move on and do what is actually helpful is crucial.

Part of having the opportunity to do the right thing (even when nobody is looking and it’s not online) is to be grateful for the time others take to drop you a line to say hey, just so you know…

Sometimes that note won’t be friendly. Because maybe you’re the third person who had to be given the same message and your unofficial teacher is tired. Maybe it’s because this is their life and it’s not yours and you made them use what little energy they had left on you. If you’re committed to learning, you need to be committed to unlearning too. And you need to recognise the labour that goes into teaching. If someone is kind enough to be your teacher, it’s probably not their ideal way to spend their afternoon, especially when the mahi needs doing. So simply saying thank you and taking it in is the best way we can all start reprogramming our brains to recognise we’re in an online classroom. And we’re lucky enough that someone cares enough to provide a free lesson.