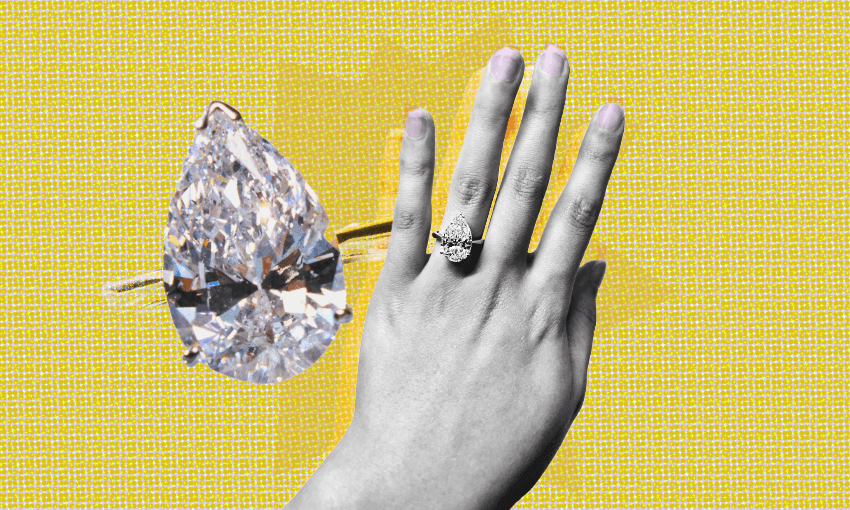

The biggest and most expensive diamond ring to be auctioned in New Zealand went under the hammer in Auckland on Sunday. In the name of luxury, Gabi Lardies went and tried it on.

The bubbles are on ice, the scented candles are lit and I am quite explicit about not being able to afford the ring which has been valued at half a million dollars. There it is on my finger, a giant sparkly pear shaped diamond – wonky, because the platinum band is far too big.

Webb’s head of fine watches and jewels Christine Power has brought it out for me on a little black velvet tray. She is wearing a few diamonds of her own, encrusted on her fingers and wrist alongside a bangle I know is Cartier, because I saw one in the auction catalogue (sold for $14,937.50).

She explains to me why this is a particularly epic diamond. It’s near colourless and clear, and has been cut in a way to refract the most light (aka sparkle). Even in the dim light of the showroom the little pear is bright. Though the retail price valuation is a neat half a million, the estimate of where the auction will reach is $270,000-350,000. It’s the biggest and most expensive diamond that she has seen for auction in New Zealand – a rarity, she says, that has attracted interest locally and from overseas.

Quite a few people have come to try it on. The ring suits everyone, she says, because of its traditional and simple design. And I needn’t cross it out as a future possibility – you never know what might happen in life. Apart from that we do know that in Aotearoa the single biggest determinant of our financial success is our parents. When my parents got engaged, there was no ring involved, instead they saved to go on a honeymoon.

We’re at the final viewing of Webb’s’ September Fine Jewels, Watches & Luxury Accessories before the 190-lot auction this afternoon, and it’s busy. There are several small groups of people looking at the other jewels and watches, which at tens of thousands of dollars seem comparatively affordable. Some of the people seem normal, and some of them seem like they have never had to worry about such menial things like doing the laundry, cleaning the toilet or clipping their toenails.

Perhaps it’s a little peep at what all our lifestyles could be like under fully automated luxury communism (except it’s humans that do these things for them, not machines). I cannot imagine the ring on my finger being within my reach in any other circumstance. Is the ideal future of humanity us all drinking bubbles on Sunday afternoon hanging out around diamonds, while machines sort out everything else? I am not against that.

I expected the diamond to be heavy, but it’s not. I also expected that when I wore it I might feel like a different person, but it is more like when you try on a padded bra and for a second you think “woah” and then it feels slightly ridiculous and you decide your proportions are fine just as they are, actually. Sitting down with Power, I feel I can only say nice things about the diamond, but in reality, it feels utterly useless in my hand. A clunky piece of jewellery that doesn’t fit, and has a sharp point. When I touch its faceted surface, my finger leaves an oily print. I hand it back to Power, who returns it to the class cabinet where it sits on a small black leather holder alongside the other glittering jewels that will be auctioned today.

Before the auction, I go back home to do my laundry, the dishes, all the things that it’s nice to do before the work week starts again. I am not daydreaming of being able to afford a massive diamond, but I would like to buy a little house some day.

When I return to Webb’s the rows of plastic chairs facing the auctioneer are full. There are people standing around the back in sneakers and jeans and kitten heels with silk dresses. A man wearing airpods and a blue checked suit the auctioneer describes as being “fetching” is topping up glasses of bubbles. To the side, two children on a modernist leather couch watch an iPad.

Most people have the A4 catalogue open, with the diamond ring as its cover star, and are making notes in it. There are a lot of monogram patterns on their clothing, the Gucci Gs and Coach Cs and other things I do not recognise. To bid, they have registered at the counter and received a numbered paddle to hold up. This is a relief because it means I can’t accidentally bid by stretching or itching my forehead. At the open bar, I refuse bubbles, because I am a professional, but do take two mini packets of Proper Crisps because I forgot to have lunch.

Most lots have one or two bidders, either from the floor, via the website or over the phone. Some have no bids and are passed on. Lot 47, a Hermès Noir Togo Birkin 35 Bag, which appears to be a fairly ordinary black leather handbag with a little golden lock hanging from its strap, sets off a bidding war. A man in the last row battles an online bidder. The estimated sale price started at $11,000 but they finally end on $26,290. “Someone is going to be very happy,” says the auctioneer. I think it is going to be whoever sold it, and Webb’s.

As lots pass, people quietly hand in their paddles to the counter and leave. Almost everything on sale is feminine, delicate jewellery and handbags, but most of the bidders are men – some of them fielding jabs from their wives or partners to bid again.

The diamond ring is lot 59. The auctioneer takes a small pause, probably because it is, by far, the most expensive thing to be auctioned today. Then he calls it “important” and says “a lot of people have come to try it on” (me!). “It’s the biggest we’ve ever had.”

He begins bidding at $2,010. A small stir moves in the room and I seriously consider bidding even though I didn’t register for a paddle. I imagine shouting across the room “I’ve got the money!” Then he realises his mistake. He meant to say $210,000. “There are too many zeros for my brain today.” A few people laugh and a perfectly made-up lady behind the jewellery cabinets is visibly and audibly relieved. Then, the room is silent.

The auctioneer repeats his request – “do we have a $210,000?” It comes from the online bidding desk. Then there is nothing, despite the auctioneer’s stalling. “Fair warning: going once, twice, three times.” The wooden hammer hits his lectern. But the diamond does not sell. The reserve price has not been met, though he says, “we are close”. Powers is ushered outside for a short TV interview.

I was hoping to see whoever bid on the diamond, to get an impression of what kind of person can spend hundreds of thousands of dollars on a rock, but bidding online is faceless. A young employee sits at a booth with a laptop and calls out “bid”. When I get home, all I have is some photos on my phone and two empty chip packets to remind me how other people live their lives. I look up the price of robot vacuum cleaners – there’s one for under $400. It is not sparkly, but still seems like a lovely taste of automated luxury.