Women and non-binary people in the music industry have spoken out about how cis-gendered men can make their jobs safer.

Content warning: sexual assault, harassment and discrimination.

*Some names have been changed.

Yesterday an open letter penned by musician Anna Coddington (Ngāti Tūwharetoa, Te Arawa) was made public amid the fallout of Alison Mau’s exposé for Stuff of the predatory behaviour of two senior music executives. Co-signed by Lorde, Bic Runga, Anika Moa, Tami Neilson, Hollie Smith and Mel Parsons, the letter states that if the job of artists is to be “vulnerable enough to create moving music” then the job of those in the music industry is to support artists “without crossing boundaries and taking advantage of them”. They made a raft of recommendations that included learning about consent, listening when people say behaviour makes them uncomfortable, and diversifying workplaces.

A number of music industry figures have spoken to The Spinoff about the practical and material changes they too want to see in their industry.

Long-running, systemic issues are nowhere near fixed, and permeate the industry from top to bottom. Those spoken to include women and non-binary people who have worked as musicians, technicians, promoters, managers and label executives, whose experiences range from inappropriate jokes and touching, being made redundant while pregnant, pay disparity with male counterparts, to losing work due to not being men.

Inclusion riders, codes of conduct, men stepping aside for non-male artists and technicians, and funding incentives are all changes that can be made right now.

Stuff’s investigation named Scott Maclachlan, the man who discovered Lorde at age 13 and then managed her, who was stood down from his role as senior vice president at Warner Music Australasia after a 2018 sexual harassment investigation. Also named was Paul McKessar, a director at CRS Management (he has since left the company), who initiated inappropriate relationships with two young artists he managed, former Openside lead singer Possum Plows and Lydia Cole.

There are echoes of another moment that rocked the alternative music scene five years ago – when allegations of grooming and sexual assault by Cheese on Toast founder Andrew Tidball were reported by The Spinoff. While many thought it would be a catalyst for meaningful change, others believe not enough has been done since then.

I’m so glad the music business is having a moment of reckoning… there’s more where that came from. Much more. One of the main reasons I got the hell out of that industry.

— Lizzie Marvelly (@LizzieMarvelly) January 25, 2021

Wellington musician Kiki van Newtown says they have been part of a number of initiatives around support and safety in music since that revelation, and is frustrated that they’ve all come to a dead end. “Countless conversations, email threads, community restorative justice panel planning… the ball has always been dropped by white men who have the authority in that situation.”

Van Newtown says external checks and balances “must be put in place to force change”.

“At a policy level, music entities should immediately commit to workforces that reflect society, including funding no less than 50% female and non-binary acts and festivals, and substantial funding boosts for Māori and Pasifika artists.”

Both Scott Maclachlan and Paul McKessar are former members of the Music Managers Forum (MMF), a voluntary, not-for-profit industry collective funded by the NZ Music Commission, which is in turn funded by the Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Van Newtown says that organisations like the MMF need to implement safety measures, especially when older men are paired with young artists who rely on them for guidance. “I would like to see the MMF making it mandatory for all members to have undergone some sort of training on harm prevention and trauma-informed responses.

“There should be standards and if they’re not met, that should affect their funding opportunities.”

Sarin Moddle works in event production, and was the marketing director and on-air talent at student radio station 95bFM for seven years. She says industry professionals are already developing best practice that she’d like to see emulated more widely. She cites drum’n’bass act The Upbeats and their use of an inclusion rider, which stipulates that the lineup of acts and/or technicians at a show or festival should meet a diversity threshold.

“I want more production managers proactively seeking out non-male techs, even if it means hiring someone with less experience, so they have the opportunity to get more. I want more event producers like [APRA’s] Lydia Jenkin who tells me when my male counterparts are asking for a higher rate and, without questioning it, gives me that same rate. I want dudes calling each other on the way they talk about women, and not just when we’re in the room to witness it.”

She says individual responsibility is needed. “I don’t give a shit what the ‘industry bodies’ do, I care what individuals do. And I want all the men who claim to value and support us to show that with their actions. Make material sacrifices to support us, because we are expected to make material sacrifices every day.”

https://twitter.com/villettedasha/status/1353941114751832064?s=20

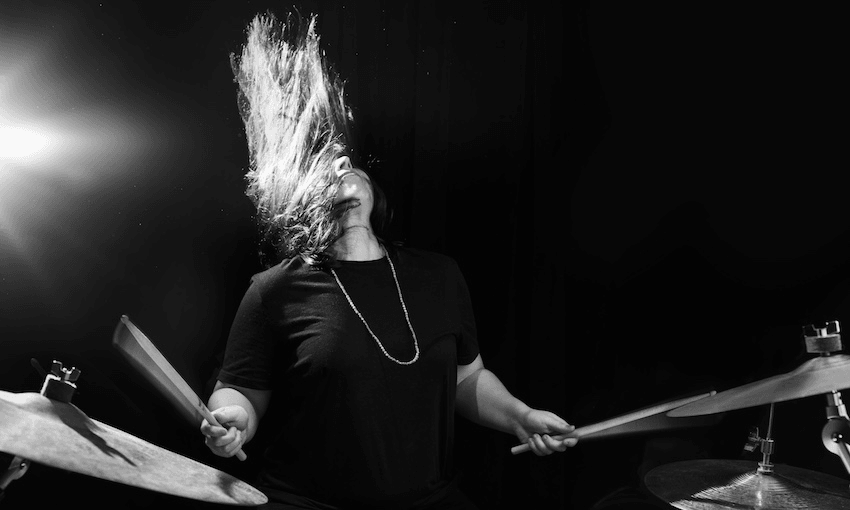

Tour manager, former label owner and drummer Fiona Campbell (Ngāti Kahungunu) has experienced the fallout of similar revelations in her music circles in the US, where she lived for 14 years until recently.

“Venue owners, bar staff and promoters have a duty of care to their patrons, employees and talent in their spaces,” she says.

“I want these people to all include safety of non cis-gendered bodies in their meetings, and have a code of ethics backed up by some training and continued engagement with the NZ Music Commission.

“They should be trained in what to do when fucked shit happens and how to deal with it. Everyone should have resources available and know at the very least what to say/not to say, and how to interact with a situation in real time. After care is also important – following up on a situation, understanding things can come out or memories develop days later, especially if there was drugging or alcohol involved.”

To men who have been told they have harmed others, she says: “Centre the harmed party.”

Campbell says too often their first response is to go into defence mode and use their relationships with other women to “prove” their innocence.

“Listen from a non-defensive space. This goes for venue owners, bar staff and promoters who hear about things happening at their shows or on their watch – be mindful of making excuses and using your proximity to other women as shields.”

Campbell says ultimately, men need to support each other to do better. “Step up more for the emotional labour of retraining other men out of these antiquated ways.”

Lauren* is a musician, guitar tech and audio engineer who has been working in New Zealand and Australia for over 15 years. She says working on music festivals, the hours are long and often involve sharing long van rides and accommodation with men “who make you feel uncomfortable or unsafe”.

“Major production companies don’t take harassment claims seriously when you bring them up, and there is gatekeeping over “big” gigs – it doesn’t matter how competent a woman is, she’ll have to fight tooth and nail to be an FOH [front of house] operator at a big festival. I have been told in the past that a big corporate client ‘doesn’t want a woman out the front because the CEO needs to trust the sound person’. And I have turned up to countless shows and been asked ‘When is the sound man arriving?’”

She says festivals like Grrrl Fest in Waikato and Milk & Honey Festival have made a huge difference. “They’ve put an emphasis on hiring female techs and crew as well as performers. This is perhaps something other festival bookers could take notice of.”

One of the founders of the three-day creative arts festival Grrrl Fest, Kat Waswo, says the Stuff story reiterated why events like theirs are still needed, “particularly in leadership and ownership roles. Women still need to provide safe spaces for each other, especially in these male-dominated creative industries.”

Waswo says as the mother of two boys, she hopes they grow up in a world “where female leaders, musicians and technicians have gained some equity in the creative industries – and that there are easier avenues and support systems for victims to report issues and crimes without fear of losing their positions”.

The NZ music industry, its legacy artists & affiliated industry complexes OBVS need to study ur local independent queer artists, kaupapa driven/POC led scenes & underpaid underground frameworks waaay more. The difference in privilege & discourse quality is really embarrassing wow

— Jessicoco Hansell (@kuiniqontrol) January 26, 2021

Kate* was a manager within one of four major record labels in the late 2000s and describes the culture as “insidious” and “bullying”.

“Homophobia, racism, sexism, sexual innuendo – anything was up for grabs as long as it was framed as a joke. Women were called names like ‘Flossie’; they’d talk about what other women in the office were wearing; we’d watch a new music video and they’d be like, ‘oh she’s chunked up’.

“It became apparent pretty quickly that if you weren’t in on the joke, you became the target of the joke, so the safest place to be was in the fold of the boys’ club… but you were never in the boys’ club.”

Touring artists and their entourages making sexual advances were par for the course, she says, and scenarios such as being asked to rep songs at a certain radio station because the programme director “had a crush” on her were common. She was also made redundant while on maternity leave due to a “restructure” of her role alone. The young man covering her leave was reassigned her job, which remained essentially the same. She says she knows of three other women at another music label who were also made “redundant” either while on maternity leave, or just before taking it. “Why do we have to deal with all this shit just to do our jobs? They don’t!”

https://twitter.com/emilywsaudio/status/1354261976101179394?s=20

Kate worries that any material changes made by the larger organisations as a result of the latest revelations will be “about how things look”.

“Say the right things, put out the right press release, say you’ve got zero tolerance. There’s an old guard that still exists, there’s still a boys’ club. But I don’t think that’s an argument not to do anything. If they do implement protocols and a code of conduct; if there’s training, even if it’s done for the optics, it sets a precedent. I’d like to think the people coming in will be the start of a new, diverse generation of people who will disrupt the old ways.”

In 2020, Massey University was commissioned by Apra/Amcos, the organisation that collects and distributes song writing royalties, to create a diversity survey of its New Zealand members. The resulting report offered some alarming findings – 70.1% of women had experienced bias, disadvantage or discrimination based on their gender, and 45.2% of women reported not feeling safe in places where music is made and/or performed. Catherine Hoad, one of the two investigators for the survey, is a senior lecturer at the school of music and creative media production at Massey University, Wellington. She says that although she and co-researcher Oli Wilson weren’t resourced to create strategies off the back of the research, they did have conversations with the Ministry for Culture and Heritage and other bodies that had the ability to affect policy changes.

Some of the findings were “upsetting, shocking but not necessarily surprising”, she says.

“We know anecdotally and from overseas studies that women and non-binary people have a not very good time in the music industry. But 70%… the fact that it was so high, was quite stark for me.”

Hoad says she would personally like to see more targeted funding for marginalised groups. “There’s so many groups already doing amazing work at a grassroots level, like Girls Rock Camp and Equalise My Vocals, Arts Access Aotearoa, who have long been really amazing champions for increasing accessibility for spaces. More support to get organisations like that off the ground.”

Aside from the funding and industry agencies and the three major labels, practitioners and administrators of live and recorded music are mostly small businesses. For employees on small teams, when the owner, manager and HR department are all the same person, recourse for complaints can seem non-existent.

Employment lawyer and HR expert Cassandra Kenworthy says there are measures small business owners and their employees can take in preventing and addressing harm.

“Ideally before anything is an issue, you want to have a policy in place,” she says. “You might have a code of conduct. You might have a specific sexual harassment policy. You will have a health and safety policy. You might even include something like a drug and alcohol policy.” She says that in sectors where alcohol is a natural part of work events, this can include assurances that the company will ensure staff get home safely, or a stipulation that one person in the organisation must stay sober at every event.

Codes of conduct have to be living documents, she says, not put in a draw and forgotten about. “It should be mentioned whenever it’s relevant, and it’s something all your contractors and suppliers are aware of and also bound by.” For labels and promoters, she says that can include touring artists and their entourages.

If someone has a complaint that they’re not comfortable taking to management, she says there are third parties that can help.

Kenworthy recommends EAP (Employee Assistance Programme), a service that employers can subscribe to, which offers their employees anonymised counselling and HR services. She also suggests contacting a union (which for musicians and music industry practitioners in New Zealand is E Tū). “They can get free legal advice at the Community Law Centre. Complaints can also be made to the Human Rights Commission, or Worksafe, who is the health and safety prosecutor, and then the other option is, if the organisation is a member of an industry body, making a complaint directly to them.”

Another channel being built specifically for the music industry is SoundCheck Aotearoa, an “action group” whose aim is to create a safer and more inclusive music community. The website lists 17 collaborator organisations, including Apra/Amcos, MMF, the NZ Music Commission, IMNZ and Recorded Music NZ.

In response to a statement by CRS Management, which said it would be working with SoundCheck “in building a safe and inclusive culture”, country musician Tami Neilson expressed concerns that it wasn’t an independent organisation, rather one made up of people who have worked with or for CRS. Rap pioneer Teremoana Rapley also questioned the efficacy of a “resource website”, calling it “an ambulance at the bottom of the cliff, again”.

View this post on Instagram

Representatives for SoundCheck told The Spinoff that around 30 “key staff” have already undertaken professional respect training with a sexual harm prevention expert, which was attended by both men and women. There are also plans to develop an industry-wide code of conduct and a formal complaints procedure, after a consultation period with the sector. They don’t currently know when that will begin, but gave assurances it will be open to everyone, not just their partner organisations.

Industry professionals are eager to see changes sooner rather than later, but say ultimately it’s not up to women and non-binary people to teach men not to denigrate and assault others. Aside from a handful of statements, there has been comparatively little public discussion by men about the changes that need to happen.

As RNZ’s Music 101 host Charlotte Ryan wrote in a stark piece for Ensemble, “It should not be about educating women about how to avoid situations or behaviours.” The work needs to be done by every individual and every organisation so that women and non-binary people can go do their jobs without fear of harm or exclusion.

This story was amended Sunday 31 January: Scott Maclachlan and Paul McKesser are former members of the MMF, not current or long-term members.

HELP – Call 24/7 (Auckland) 0800 623 1700, (Wellington) 04 801 6655

Rape Crisis – Ph: 0800 88 33 00

Aviva Canterbury sexual violence crisis service – Ph: 0800 284 82669

Tū Wāhine: Kaupapa Māori sexual violence crisis service – Ph: 09 838 8700

MusicHelps Wellbeing Service – Ph: 0508 MUSICHELPS

Te Puna Oranga: Kaupapa Māori sexual violence crisis service – Ph: 0800 222 042 info@tepunaoranga.co.nz

Male Survivors Aotearoa – Support for the well-being of male survivors of sexual abuse

Shama: sexual harm support service for ethnic communities – Ph: (07) 843 3810, Txt: 022 135 9545