Today, one year ago, Chris Mirams lost his mother in an instant. Her sudden, wrenching death sent him into a spiral of unrelenting grief. From this darkness came an unexpected saving grace – Māoritanga and whanaungatanga.

This story was originally published on Emily Writes Weekly.

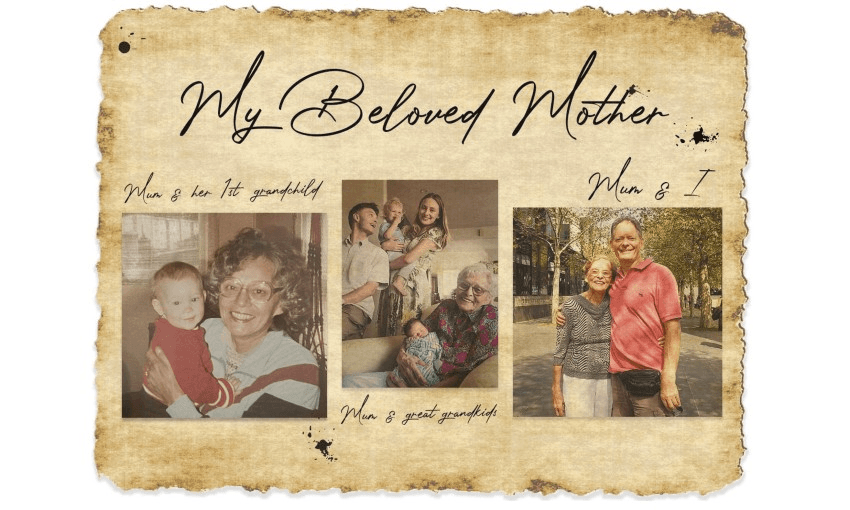

My 91-year-old mother, a determined, resourceful and independent woman, was hit by a van and killed while riding her mobility scooter around the neighbourhood she had lived in for 23 years. It was May 29 last year and a normal day at work for me until I received a call from a police officer with the devastating news. Then, in a matter-of-fact way, he asked if I could come and identify her at the scene.

When I got there, 40 or so minutes later, the busy thoroughfare road was closed, media hovered and an ambulance waited to take her body to the morgue.

It was three hours after the accident and she lay alone in the middle of the road covered by a blue tarp. Her mangled scooter, having been lifted off her, was on the curb nearby. The autopsy would later reveal the bone shattering impact the more than two-tonne van had on her 46kg body.

When I lifted the tarp, I was met with the fixed gaze of her wide-open eyes, sunken cheeks, and unfamiliar pale skin. Blood had flowed from her right ear and formed a small pool amongst the gravel and tar-seal under her head. A theatre nurse on her way to work was one of the first on the scene and tried resuscitating her. As she did that, another driver stopped and he held my mother’s hand and prayed aloud.

Everything that happened from receiving the phone call to this moment was hard to absorb.

The only coherent thought was running on repeat, how violent and unfair her end was.

As I knelt beside her, all I could think about was everything she had sacrificed and overcome so she could make my life better than hers. Torn from her roots and raised in an orphanage, then a 30-year-old Māori widow with a toddler in 1960s New Zealand, working 18-hour days to give me the golden ticket of education. Proud as punch as I progressed my career.

After a few minutes, I kissed her forehead and pulled the tarp back over her face.

This was the easy part.

Death is the only certainty in life yet many of us are unprepared for how to cope when a loved one passes. Last year, more than 900 New Zealanders were lost to violent and unexpected death in road accidents and suicide, leaving thousands of survivors like me grappling with grief without a compass.

As an only child, I felt truly alone for the first time in my life and grief bit hard.

My inner voice was an avalanche of what ifs and if onlys, I was riddled with guilt for imagined things I could have done better for her. For weeks, fog clouded my brain. I could walk into a room, get into a car or open the fridge and forget why I had done that. Sleep was elusive, mood swings were severe and trying to wrangle the array of emotions was an endless, exhausting game of whack-a-mole.

Amidst the emotional turmoil, there are so many decisions to make in such a condensed timeframe – organising the cremation, a service, closing all sorts of accounts, sorting through belongings and dealing with a probate system that’s a shambles. Then, for sudden deaths, there are other bureaucratic processes to endure.

The police investigation is thorough but is never going to be fast enough. The callous coroner’s court will suck the marrow out of your bones if you let it. Seeking an update after two and a half months, my liaison told me in a stern matron’s voice, “I’ve got 250 files and I can’t send emails to every one of the families”.

I haven’t heard a word from them for more than six months.

I thought that getting all this sorted quickly was the path to peace and closure, but I discovered differently.

The commonly accepted five stages of grief did not fit my experience, nor did counselling or the stoic Kiwi attitude that stems from our English ancestry.

What I did learn is that grief is messy and unpredictable and that help can be found in the most unexpected places.

Through reading and research – in particular neurologist Lisa Schulman’s book Before and After Loss – I discovered grief rewires our brains and alters our perception of threats. Even though we may not consciously see the loss of a loved one as a threat, our brains perceive it that way and trigger the fight or flight response. This flood of stress hormones leaves us at the mercy of our emotions. From there, you’re in the lap of the gods.

One evening, four months to the day after mum’s passing, my wife Juliet and I were sitting in our lounge tired and deflated. She turned to me and said “we have to do something different; we can’t go on like this. Your mother has a curse on you and I can feel it in her house, and parts of ours as well. You need help, spiritual help.”

After a few moments to take that onboard, I asked, “Do you mean with the iwi?”

“Yes, I think that’s what you need to do.”

To do that came with complications. My mother was from Ngāti Pāoa but felt betrayed by her heritage and passed down her ambivalence to me. She grew up on iwi land on the Hauraki Plains with her seven siblings.

Her Irish father built the family home and developed a lifestyle block so they could be reasonably self-sufficient. They rode a horse or walked to school, fed the animals and worked the gardens as part of their chores, cousins were all around. Life was simple and happy.

But after her mother’s death while giving birth to the last child, life nose-dived and she carried the impact of it for the rest of her life.

There was no desire for half caste kids and a non-Māori head of family to be on the land and the children ended up in an orphanage on Auckland’s North Shore. Making the wound deeper, the land was lost to others in the extended family. For mum, all this led to a lifelong distrust and disconnection from her roots and culture.

A day after the conversation with my wife and not knowing what to expect, I sent a short email to a generic address for Ngāti Pāoa. I outlined my situation, asked for help and gave my mobile number as an alternative contact. A few hours later I missed a call but got the follow up text to contact Hau Rawiri, a former treaty negotiator for Ngāti Pāoa.

The next morning we had a long conversation. I explained mum’s life experience, our subsequent lack of cultural connection and my desperation to find peace. Hau was incredibly compassionate, calm and understanding, reassuring me there was no issue with any of the back-story. Rather, the focus was on helping heal us as a whānau and helping my mother’s spirit understand it was time to pass to the other side. There was also, he was adamant, an urgency to doing so given the length of time since her death and the impact he could feel that it was having on us.

“So, are you and your whānau available tomorrow morning?” he asked. “We will do blessings at your mother’s house, the accident site and your house.” So, at 9am on that Sunday morning with my wife, son, one of my daughters and my mother’s ashes, we met with Hau and his wife Maea outside mum’s house.

From subsequent reading, I’ve learnt that when a person dies Māori believe their wairua or spirit remains until they are laid to rest. That starts from the moment of death.

Traditionally, the body is never left alone by whānau until the burial or cremation and caring for the body can be seen as the last act of love.

Karakia and prayers have an integral role in acknowledging the spiritual elements of life and strengthening the relationship between the living, ancestral and spiritual worlds.

The tangihanga is similar in concept to the European funeral service but far different in how it is performed, full of emotion, storytelling, song and prayer. Processes such as autopsies are abhorrent to Māori, as the respected East Coast GP Paratene Ngāti wrote in his essay ‘Death, dying and grief: a Māori perspective’.

‘The physical coldness and isolation of the hospital mortuary is contrary to Māori views that deceased must be kept constantly warm and comfortable by the presence of kinfolk, in order to calm the soul and assist it on its journey to the spirit world.”

For my mother, everything that had happened since her death was contrary to this. It must have been so confusing and disorienting for her spirit. As we stood outside her house with Hau and Maea, I felt a sense of hope for the first time. The irony was not lost on me. My mother was going full circle, back to her roots via the culture she lost and which I had never found.

In Māoridom, the roles and responsibilities of men and women are quite defined in this type of ceremony. Women have the first say and Maea started with a Karanga, a call to summon ancestors of Ngāti Pāoa, Ngā atua Māori, the Māori gods, and mum’s extended family to come for her and clear a spiritual path so she can cross to the other side. It was mystical and moving.

Then, Hau followed with the waerea, ancient incantations to clear bad energy and omens. This began outside the house before he led us inside and through each room in a precise and measured way, touching the walls as he recited the rituals in a calm but firm tone.

We finished in the lounge that looks out onto the street where mum used to sit and watch the comings and goings in a big La-Z-Boy chair. Then, we shared some kai, a lemon cake my wife had made, and talked through what we had done. We then did versions of this at the site where she was killed and our house, across town.

At the site, as I tightly held the white pine box with her ashes, I told mum that she had succeeded in her goal of giving me, and by extension our children, a life better than hers. That her sacrifice was a gift I am forever grateful for. I also told her it was time to go, that my father, her parents and brothers and sisters were waiting and wanting to see her again and that we would be okay for her to move on.

It was a very emotional and draining day, yet spiritually uplifting. Afterwards, as we all sat in our lounge reflecting on the last few hours, there was a sense of peace not just in my head and my heart, but as a presence amongst us.

The difference emotionally and mentally between the start and end of the day was remarkable and I am pleased to say it has continued. I went from existing to living, her house felt like a home again and I can drive past the accident site and acknowledge it without feeling sad, angry or alone.

The experience has changed my perspective on what the spiritual approach of Māoridom can offer us. From my experience, when death comes calling, this is a door worth opening. There are other aspects of life I’m sure it can benefit, which I will explore in time.

“You don’t have to be Māori, that’s important,” Hau explained to me a few months later. “It is what we do but how can the process help others to find closure, that’s the real art. It’s about raising the consciousness of people about their connections back to their heritage, even if they’re not Māori.

“Everyone dies and everyone will deal with it differently, this is another perspective and way to help people get through all of that.”

A week earlier, I had decided to keep a small urn of mum’s ashes as a comfort.

Hau gently suggested it might be good to put all her ashes together again so she could be whole, and so I did. Early on, I had decided to reunite her with my father, the love of her life who died suddenly at the age of 32. He had served with J Force in Japan and is buried in the armed services section of the Karori Cemetery in Wellington.

Hau thought it would be good to do that sooner rather than later. It would be the final act in mum and I letting go of each other.

Just over a week later, on a rainy Saturday morning, with the cemetery to myself, I put her ashes into the pre-dug hole, covered it with dirt and said goodbye. The circle complete for everyone.