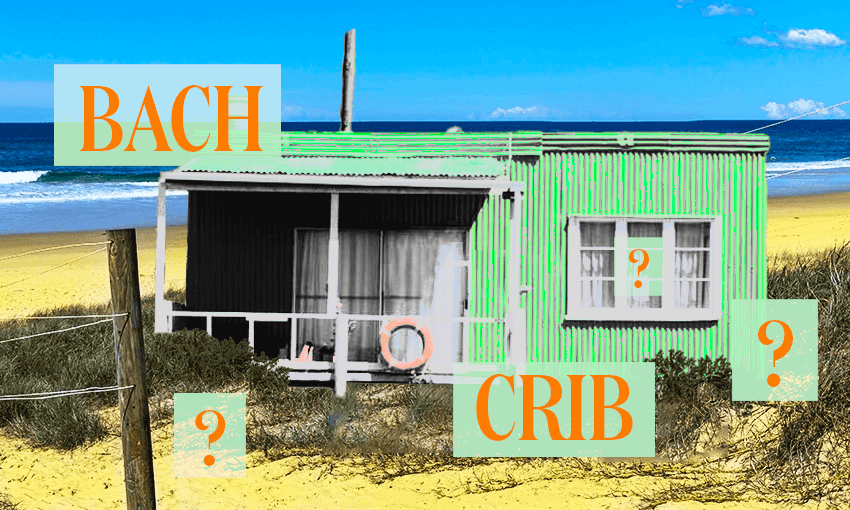

Summer reissue: Alex Casey goes on a linguistic journey to find the true difference between who’s using ‘bach’ and ‘crib’ across our fair nation.

The Spinoff needs to double the number of paying members we have to continue telling these kinds of stories. Please read our open letter and sign up to be a member today.

When Southlander Jade Gillies thinks of retreating to a sun-soaked holiday home, it instantly evokes feelings of nostalgia and rustic charm. “It’s got a melamine table and some vinyl chairs and mismatched cushions,” he says. “It’s certainly not brand new and it’s seen a lot of seasons of holidays and a lot of different families. It’s got that retro-ness that is a little bit like stepping back in time, back to the way things used to be.”

This magical place is also, he asserts firmly, called one thing and one thing only. “It’s most definitely a crib,” he laughs. “Always has been, always will be.”

He should know. Gillies runs South Stays, a company that manages 30 holiday properties between Invercargill, Riverton and Colac Bay. He’s also a fifth generation Southlander, and has very fond memories of holidays spent at the crib that his grandparents owned. “We’ve always referred to it as a crib. We’ve never had baches in the family,” he says. “And, if we were to ever get our own holiday home, that would always be called a crib as well.”

But about 1,250 kilometres away in Doubtless Bay, Gillies’ Northland counterpart David McLeavey, aka the Bach Man, has his doubts about “crib”. “My immediate thought is a newborn’s bed,” he chuckles. “Or that MTV show where rappers would say ‘welcome to my crib’ if you can remember that.” Having managed holiday homes in the Far nNorth for over 15 years, he is steadfast in his view: “If I’m thinking about a little house by the coast, I’m thinking about a bach.”

These two men represent the yawning divide that exists between New Zealanders when it comes to referring to our beloved holiday homes. “In the New Zealand Oxford English Dictionary you get definitions for both ‘crib’ and ‘bach’,” explains Dr Andreea Calude, associate professor in linguistics at the University of Waikato. “But interestingly ‘bach’ is just a regular item whereas ‘crib’ is marked as colloquial, predominantly for South Island speakers.”

Bach is likely derived from the world bachelor, which Calude posits may relate to the North American idea of a bachelor pad. “Just a single one bedroom apartment or house, quite simple and uncomplicated,” she says. In post WWII economy, Calude says that some New Zealanders found themselves able to buy a second section, and plonk a caravan on the land that would eventually turn into a shed, and then a small dwelling. “Those things became baches,” she says.

David “Bach Man” McLeavey subscribes to a slightly different theory. “In the early days, the European settlers came up here to spike for Kauri Gum. Most of them were single men who lived in these ramshackle little huts made of slabs of kauri and canvas,” he explains. “But then they would meet a woman and want to get married, but the woman would say ‘I will marry you, but there’s no way I’m going to live in that little shitbox that you live in’.”

As far as he is aware, that’s where the term came from – “the term bach became attached to these little ramshackle houses, because they were all occupied by bachelors,” he chuckles. “All of these Slavic men that lived in these little dumps, and fell in love with women who refused to live and raise a family in there.” Rather appropriately for a man known as the Bach Man, McLeavey is also a bachelor himself. “It fits me good, I just love that story,” he says.

Crib is harder to trace back, but certainly predates Xzibit’s use of the word in the 2000s MTV series. “For more colloquial words, it’s very hard to pinpoint down the origin because they are spoken and so we don’t have very clear trajectory paths,” explains Calude. “Some people use crib to talk about a holiday home, some people use crib to talk about a prison cell. Crib can also mean one’s lunch, and is also linked to a cribber – someone who copies or cheats.”

Without including it in the Census, it is hard to get data on the frequency and popularity of each term, but Trade Me can provide a snapshot. “When it comes to this debate, there’s a clear winner with 732 listings for the term “bach” or “batch” and just 25 listings for the term “crib” for sale on Trade Me Property,” advises Gavin Lloyd, sales director at Trade Me Property. On both Trade Me and Holiday Houses, the “vast majority” of crib listings are in the South Island.

In 2011, Dr Kevin Watson from the University of Canterbury surveyed 1000 New Zealanders about their use of local words, and found that the majority of people used the term “bach” instead of “crib”. “The word bach has been around as long as many people can remember,” he said at the time. “Most of the participants in the survey, from teens to their 70s, used this.” When “crib” did appear in the survey, respondents were much more likely to be from Invercargill or Dunedin.

Trying to pinpoint precisely where a bach becomes a crib is a challenge, but our expert holiday home proprietors were happy to guess. “Crib is very much a Southland term,” says Gillies. “But I wouldn’t be surprised if the term is sneaking slightly into South Otago, and maybe some places on the West Coast.” Up north, McLeavey thinks there’s an obvious landmark dividing the terms. “I would guess the Cook Strait is where it changes. In Wellington it is a bach, and in Motueka it is a crib.”

That’d make for a nice, clean division, but a quick phone call to the top of the South Island revealed that the Cook Strait theory might not hold water. “No, I’ve never had anybody ask about, or refer to, a crib,” says Sian Potts, who’s been the manager of Nelson Bays Holiday Homes for over a decade. “If someone asked me if they could rent a crib, I’d think they were referring to a portacot,” she laughs. “I think if I started putting crib on my advertising, then everyone would think I had gone a bit mad.”

The complexities are no surprise to Calude. “There might be other things going on here, not just regionally. There might be things like age and social class in the mix too,” she suggests. Referencing 2001’s Language in the Playground Project, which found huge variations between schoolyard terms such as “tag” “tiggy” and “tig” across the country, she says that there are a wide range of factors that can influence one term rising over another in different parts of New Zealand.

“They found there wasn’t just a straight regional variation difference, but also urban versus rural variation,” she explains. “So depending on where the children came from, they had slightly different ideas, and sometimes religion and socioeconomic background was even a factor in the mix. It’s not as simple as the regional factor – especially because urban centres like Christchurch often behave differently to the rural centres in the South Island.”

Indeed, Trade Me also reveals some intriguing outliers. There’s one crib listed in the North Island – a charming little cabin in Thames described as “the ideal holiday crib for those who enjoy fishing the Hauraki Gulf.”

Wherever the line between bach and crib should be drawn, Gillies is proud to stand by crib, alongside many of his fellow Southlanders. “It’s what makes us different and special, having our own language,” he says. “It’s kind of cool to be different.” Likewise, McLeavey up north is happy to stick to being Bach Man. “No, I wouldn’t want to swap,” he laughs. “Crib Man sounds like he has heaps of babies and Bach Man sounds like he has none. I’m Bach Man.”

Although it may seem trivial, Calude says these colloquialisms are crucial in communicating our identity. “Language is such an important marker through which we establish groups, and also distinguish ourselves from groups that we don’t belong to,” she explains. “People will always, no matter how much you try to stop them, want to have their own idiosyncratic way of communicating things. That’s how people identify who is from their own group and who isn’t.”

Her advice to those fervent crib fans down south – and possibly on the West Coast, and possibly in Thames for some reason – is to hold onto it for dear life. “There’s no need to stamp variation out and settle on one word as a nation, because I think variation is what makes us interesting and unique,” she says. “Words also serve as a personal history of the nation – they come from different sources and tell us something about how we came to be, but also who we are.”

First published February 4, 2024.