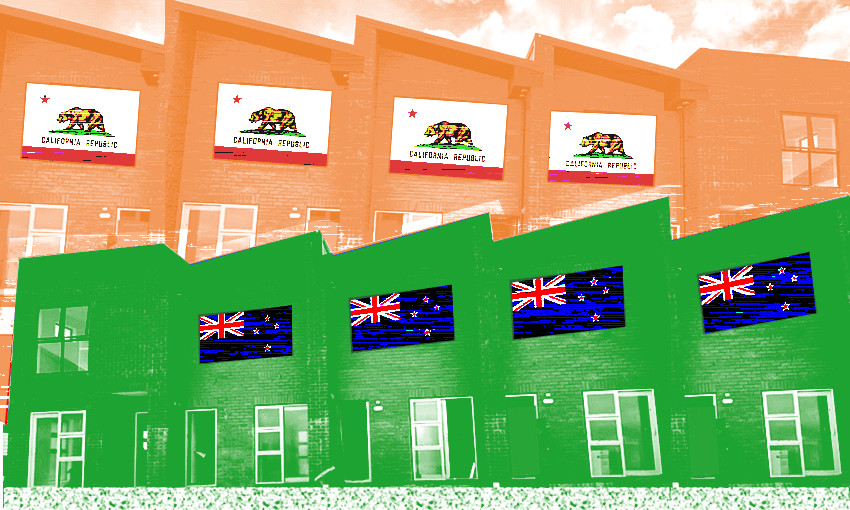

The California experience shows why giving councils more freedom to write their own housing rules can be a recipe for disaster, writes San Francisco-based expat Sarah Hoffman.

Nine years ago, my husband and I moved from New Zealand to San Francisco, where we live now. When we decided to build a pergola as part of our backyard DIY project, we thought it’d be a simple process. After 11 months, eight separate approvals, two engineering plan sets, and notifying 60 neighbours, it took intervention from our local supervisor (similar to a city council member) to get the permit approved.

For the first time I understood first-hand why there’s a housing crisis in San Francisco. The obstacles we faced for our tiny project are amplified when it comes to housing – it takes almost two years to get a permit to build a home. There’s a lot New Zealand can learn from California to avoid the same missteps.

For some context on how San Francisco got to where it is today, in 1978 the Board of Supervisors massively “down-zoned” the city, making apartments illegal in 75% of San Francisco. The result was a sharp handbrake on new housing supply, pricing low income and minority populations out of the city and causing widespread displacement and urban sprawl. The tech boom later resulted in an influx of jobs, economic growth and people wanting to live here, but with insufficient housing available. Today, the average home price in San Francisco is $1.34 million (~$2.21 million NZD) – around 24 times the average income.

As in New Zealand, it’s universally acknowledged that San Francisco has a housing affordability crisis. Yet for decades San Francisco dragged its feet on enacting meaningful changes to increase housing supply. Between the restrictive zoning rules, labyrinthine permitting process and neighbourhood opposition to anything larger than a shack, it’s a self-induced crisis. For example, when a developer proposed building a seven-storey, 100% affordable apartment building in San Francisco’s sparsely-populated Sunset district, neighbours filed a lawsuit to stop it, on the basis that the influx of low-income residents would be “bad for the neighbourhood”. Or when a developer proposed to build apartments on a department store’s valet parking lot, the Board of Supervisors voted it down due to concerns about the project’s impact on a blighted neighbourhood.

In the meantime, thousands of people live on the streets or are forced to commute for hours because they can’t afford a home here. But anti-housing groups claim that supply and demand somehow doesn’t apply to the housing market, and for years opposed any attempt to promote housing development.

One San Francisco politician, Scott Wiener, pushed back against its restrictive housing policies, first as a city supervisor, and now as a member of the California senate. He recognised that densification promotes compact and efficient land use, prevents the loss of agricultural land and open spaces via urban sprawl, and allows people to live close to their jobs, schools and transit. Increased production also decreases the per-unit price of multifamily housing, allowing low-income and young families to get onto the property ladder. And dense housing isn’t necessarily low quality – our first apartment in San Francisco was 65 square metres, but better insulated, sound-proofed and designed than any New Zealand house I’ve lived in.

Faced with the inaction of San Francisco and other cities, Wiener proposed that the California legislature enact state laws that preempt local control over housing policy in order to advance these goals. In 2017, one such law waived local zoning requirements for affordable housing projects, and has sped up the approval of at least 18,000 new homes across California.

Another central policy is the “housing element” law – every five years, each city and town in California has to submit a plan to the state showing how it will ensure sufficient housing is built for the anticipated population growth. For instance, in 2022 the state directed San Francisco to plan for 82,000 new housing units, 20% of which must be affordable. If a city doesn’t submit a compliant housing element by the deadline, it loses state infrastructure funding. The “builder’s remedy” also kicks in, allowing developers to bypass local zoning rules entirely if they build affordable housing. This year, the builder’s remedy forced the upmarket city of Santa Monica to approve 3000+ new housing units after it failed to plan for new housing.

These dire consequences have motivated cities to approve ambitious housing plans, albeit reluctantly. While San Francisco supervisors raged against the state law, they ultimately had no choice but to approve the housing element. This illustrates an advantage of this “top-down” approach: it insulates local politicians from the at times unpopular consequences of approving densification. In a city where the loudest voices are moneyed home-owners who don’t want to see anything change, local politicians are often reluctant to be seen as too pro-housing. Central control allows housing to be permitted based on best evidence and objective standards, rather than subjective concerns about neighbourhood character.

Applying these lessons to New Zealand, there’s a lot to like about the bipartisan MDRS policy, which allows up to three storeys and three dwellings on almost all urban residential lots.

Indeed, the MDRS policy has been lauded as a model for other countries. National’s recently-proposed competing policy would encourage even denser housing near public transit and require councils to zone for 30 years of growth, but also allows councils to opt out of the MDRS rules.

Neither policy goes far enough. Labour’s policy fails to promote the development of large housing projects that New Zealand desperately needs. And while National has aggressive goals that, if enforced, could produce more housing, the insistence on maintaining local control will lead to greenfields development and loss of agricultural land rather than densification.

The reason that sprawl inevitably follows looser controls is that people in existing suburbs vote, but land doesn’t. Given a choice between upzoning in the face of local opposition or allowing urban sprawl, cities will opt for sprawl. And National has not answered the crucial question of how they will avoid the congestion and climate impacts of this policy, such as by providing public transit and infrastructure improvements.

National also must define how they will address a failure to meet their targets for councils. How will they “take control” of local zoning? Will they be truly willing to override the councils as Chris Bishop suggested on Q&A recently? Will they have courage to go further and employ a builder’s remedy, to offer the consequence that compelled change in San Francisco?

Both National and Labour must consider what comes next after upzoning – do we need to do more to incentivise affordable housing? Can we streamline the resource consent process to speed things up? How do we ensure existing tenants are protected? The best answer to these questions arguably lies in a cross-party approach that provides certainty and takes the sting of partisanship out of this crucial issue, and has real, enforceable targets.

New Zealand is on the right track, but unless it pursues bold housing policies it will continue towards the scenario San Francisco is trying to remedy today: many people born here simply cannot afford to stay.