Andrew Smith has been running ghostly walking tours of Dunedin for 25 years, and admits he still gets scared silly some nights. Tara Ward joins him for a stroll.

It’s nine o’clock on a dark Wednesday evening in Ōtepoti, and I’m standing on a street corner listening to a man dressed in full Victorian garb. He’s telling me a chilling story that I’ve never heard before, about the 1962 unsolved murder of a local lawyer which took place in a nearby building. A parcel bomb was delivered in the morning post, the blast blew a hole in the first floor window, and people apparently reported seeing a severed hand flying through the air.

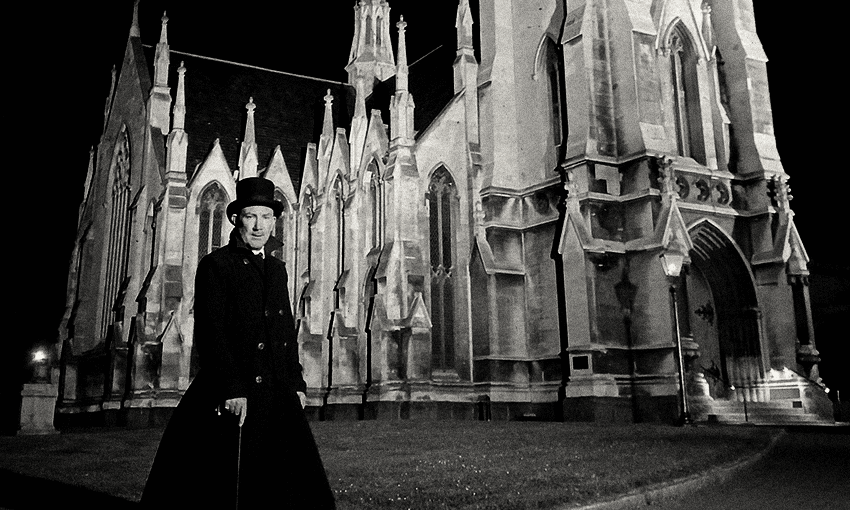

Suddenly, a pale, floppy hand hits me in the chest. Is it a five-fingered ghost? Is it THE hand, only now landing from 1962? Thankfully, it’s merely a rubber prop launched unexpectedly from the pocket of Andrew Smith, the barber and haunted historian who runs award-winning ghost walking tours around Dunedin. Moments earlier, his deep voice had boomed out from the darkness across the street. “Are you looking for a ghost?” he’d asked. I wasn’t sure. All I knew was that Halloween was fast approaching, and if I was going to write a story about a ghost tour, there was no better time to do it.

As Smith and I shook hands (no rubber props involved), he informed me the group I was supposed to be joining had been forced to cancel. So tonight’s Hair Raiser Ghost Walk would now be me and a man who had seemingly just arrived from 1865. Spooky? Seems fine. “It’s like a date,” Smith announced, and I immediately thought of the Say Yes To the Dress episode where a bride married a ghost named Eduardo. Things seemed to end happily for her. What could go wrong for me?

Smith has been walking Dunedin streets in top hat, black frock coat and cane since 1999, sharing the ghostly tales of New Zealand’s “Halloween capital” to tourists and locals alike. He admits he’s always been a fan of “dark history and horrible stories”, having been raised with the tales of his Irish ancestors who emigrated during the Otago gold rush, and the superstitions and beliefs of his strict Scottish grandmother (“she had quite a dark vibe”). A skeptic in his youth, Smith never expected to end up telling spooky stories for a living.

“I never wanted to see a ghost. I’m the last person that should be doing this, because I didn’t really believe. But I also had quite an imagination when it came to the possibility.”

It wasn’t until Smith saw his first ghost while living in the UK that he changed his thinking. Every night, Smith would walk past a stone house near Kirkstall Abbey and see the light on and a man walking around inside; later he discovered there was no floor to the building, and the man he’d seen was the well-known ghost of an abbot who died 200 years earlier. Smith’s curiosity was piqued. On his return to Dunedin, he began to explore how these superstitions and ghostly notions had influenced the city established by Scottish settlers in 1848, and started offering themed walking tours around the city centre and local cemeteries.

Smith tells me that tonight’s tour is based on a lot of Scottish superstitions, but it seems anyone hoping to say hello to the other side may be disappointed. While Smith has had people arrive brandishing spirit boxes and ghost-hunting gear, he reckons that’s not what his tours are about. “Whether you believe in ghosts or not is irrelevant to me,” he says. Rather, Smith hopes his spooky stories will connect people to Dunedin’s past, through a haunting combination of history, storytelling and atmosphere.

“My motivation for doing the tours is really this,” Smith says, raising his Victorian cane towards Dunedin’s Town Hall, its gothic stone front lit up by amber lights against a black night sky. “You know, look at it. It’s my theatre set. Nobody’s here. 25 years later, still nobody is here.”

Nobody was in the Octagon that night, but there were plenty of untimely and unfortunate deaths to discuss. First, we visited the alleyway Smith calls the “corridor of death”, which was the site of Dunedin’s first hospital in the 1850s. This is where a friendly ghost known as the original Grey Lady is said to appear, wearing her nurse’s uniform and wafting a distinct perfume. I ask him what the ghost smells like; he tells me it’s the smell of antiseptic from the public toilets down the lane.

After the incident with the flying hand, I’m not sure what to believe, but it almost doesn’t matter; Smith’s an entertaining storyteller with a huge passion for bringing Dunedin’s colonial past to life. As we stroll through the shadows, Smith launches into gripping yarns about the Leviathan Hotel’s landlady ghost, of security guards who refuse to enter certain buildings because of what they’ve seen, and a jilted bride who threw herself off the cliff behind First Church. Legend has it that seeing the selkie bride is an omen of misfortune – if only she hadn’t said yes to the dress, after all.

We wander down gloomy alleyways and brick lanes, with Smith pointing out historic features and hidden corners that I’d never noticed before. “Nobody comes out just to look up at these buildings at night,” Smith says. He loves that Dunedin residents on his tours suddenly see their city in a new light, and it’s even better when these locals begin to open up and share their own unearthly experiences. “A good ghost story is like an onion,” Smith reckons, with each new and unexpected anecdote adding another layer to these mysterious urban legends.

We walk down an alley behind the Regent Theatre, where Smith recounts the unsettling story of a tragic 1879 fire that swept through the area and killed 12 people. People who live and work here today, he says, speak of peculiar cold spaces, strange smells of smoke and unexplained sounds of crying. The Otago Daily Times reported a “ghostly gushing” as recently as 2018, and Smith says the suspected 1879 arsonist was a plumber. The pipes, the pipes are calling, Dunedin.

By the time we visit an old World War Two underground bunker deep below the CBD, I’m on edge. Smith knows his stories can make a sudden breath of wind or a quiet footstep feel like something much more sinister, if that’s what people want to believe. “Once you tell people something, how much does that feed into it?” he wonders aloud. He’s also found himself genuinely terrified on some evenings, particularly during his cemetery tours. “Some nights I think, ‘Jesus, what am I doing?’ I’m supposed to have nerves of steel,” he laughs.

But 25 years since Smith first donned his top hat and cane, interest in his ghost tours is stronger than ever. “When I first started, people would look at me and go, ‘what are you doing? Dunedin’s not old enough, there’s no ghost stories here’.” He says that over the years, ghosts have become more fashionable, and people have become more comfortable exploring their own horrible histories. For Smith, though, the Hair Raiser tours are a way of keeping the stories and memories of early Dunedin alive, with his own family’s history as a backdrop.

“I’m not out to talk to dead people, chase dead people, or invite them home with me,” he says, as we prepare to go our separate ways into the cool Dunedin night. “But as I say to everyone: if you see me running at any point on any of my tours, you might want to follow.”