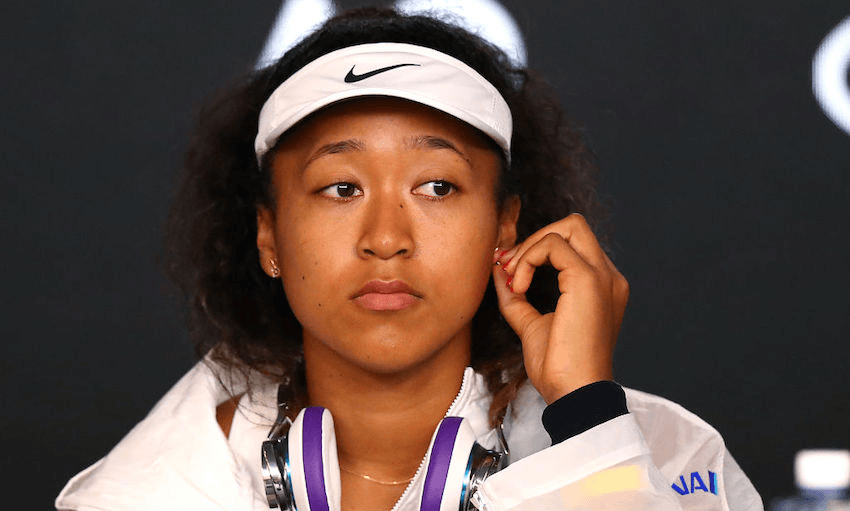

The tennis star’s health and happiness is paramount, and these ultimatums are doing nothing to help her feel comfortable in press conferences, writes journalist and media trainer Venetia Sherson.

During last year’s US Open tennis tournament, which she eventually won, third seed Naomi Osaka wore seven Black Lives Matter masks, one for each round of the tournament. The masks, she said in a post-match interview, provided a platform for her to protest injustice. “I feel like I’m a vessel at this point, in order to spread awareness,” she told reporters. The kudos was widespread.

At the same tournament, when she thrashed 15-year-old wunderkind Coco Gauff, 6-3, 6-0 she again won cheers from the crowd and the hearts of many viewers when she embraced the emotional teenager and invited her to join her in a post-match interview. ESPN described the gesture as a “lesson in humility and sportsmanship”.

So far so good.

But this week, Osaka stirred up a storm when she announced on social media she would no longer take part in post-match media conferences, citing mental health effects. “I’ve often felt that people have no regard for athletes’ mental health and that rings true whenever I see a press conference or partake in one,” she said, possibly quoting from Prince Harry’s songbook. “We are often asked questions that bring doubt into our minds and I’m just not going to subject myself to people that doubt me.”

Organisers of the French Open, at which she was playing, reacted with concern and a threat of a hefty fine, pointing out that press conferences are part of the deal. Woman up, essentially. Osaka withdrew from the tournament, leaving the event without one of its biggest names.

I have a lot of sympathy for Osaka. She is young. It’s clear she finds interviews excruciatingly painful. On court she can deliver killer blows; off court she finds it hard to parry and thrust with members of the press. She is not the first elite athlete to push back. NBA star Kyrie Irving has copped several fines for breaching media protocols. Novak Djokovic was fined after he skipped the media scrum when he accidentally hit a lineswoman at last year’s US Open.

Others have become hardened. Serena Williams can silence a dodgy question with a glacial look. Rafael Nadal, when asked by a reporter whether his game was off because he had recently married his long-time girlfriend, fired back, “Honestly, are you asking me this? Is this a serious question or is this a joke”, then raised a laugh when he asked the reporter if he was projecting frustrations from his own marriage.

There is no doubt some media questions are inane; some provocative; others woefully naive. But journalists have a job to do and those of us who will never hold a trophy high above our heads or earn a fortune for our talent live vicariously through their work. We want to know what went wrong and what went right.

So where does it leave Naomi Osaka, and where does it leave administrators? Osaka seems far too driven to walk away, which she could do if she chose. (She earned more than $55 million last year alone). Assuming she stays in the game, her mental health is crucial. Organisers have a duty of care if she holds up her hand to say, “I’m struggling.” And they need to help her find a path to a point where she may be willing again to speak to the media. That path should not be one of ultimatums, threats or indignation.

We have become so used to seeing sportspeople on camera it’s easy to imagine they automatically know how to do it. As a journalist who has worked with young sportspeople on the cusp of stardom, I have seen many recoil at the thought of a camera being thrust in their faces.

Not everyone is comfortable in the spotlight. The people around Naomi Osaka need to make sure, when she is ready, that she is given the help she needs, both in tackling mental health challenges and in providing the tools and support to navigate the media. It is absurd to imagine those skills should come as naturally – or as forcefully – as a cross court backhand.