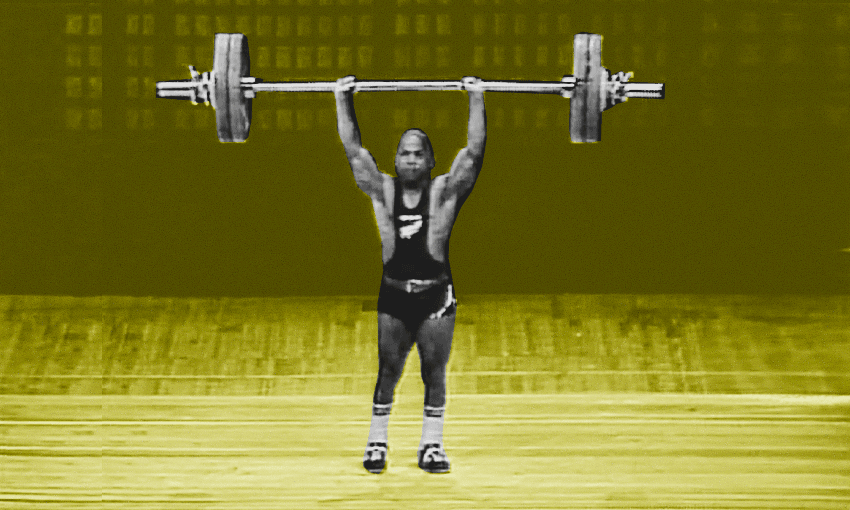

New Zealand fell in love with Precious McKenzie at the 1974 Commonwealth Games, and the feeling was so mutual he decided to stay. But the charismatic weightlifter hadn’t always been made to feel so welcome.

In an apartheid-era gym advertised as “whites only”, Precious McKenzie was about to break a national record. At 4’9” (145cm), the shortest man in the room sat quietly on the sidelines, watching the flyweight lifters reach their limits, then the bantamweights, and then the featherweights. As the bar got heavier and heavier, and with McKenzie still to begin his lifts, people began to laugh. But as the mood grew from confusion to derision, he finally rose and approached the stage. Precious McKenzie bent down, grabbed the barbell, threw it over his head, and smashed the record on his first attempt.

“I thought, ‘I am defying what the South African government is trying to do’,” he remembers. “If they think we are inferior, this is how I am going to prove that we are not.

“I wanted to prove to the world that you shouldn’t be selected by your colour, creed, or anything. You should be judged by your ability, and to me that is a true sportsman.”

By 1960, in his early 20s, Precious McKenzie was the best weightlifter in South Africa. Despite being born a sickly child with severe pneumonia, and having subsisted on the meagre rations welfare doled out to his family after his father was killed while hunting crocodiles, McKenzie possessed a strength and explosiveness that put him head and shoulders above his competition – in lifts, if not height.

In apartheid South Africa, however, simply finding a gym in which to train proved a near insurmountable task. McKenzie was frequently ousted from “whites only” facilities, bouncing from basements to firehouses to wherever coach Kevin Stent could sneak him in.

“He had a certain aura about him,” says Stent. “He didn’t look cocky – but he looked dynamic.”

Eventually, McKenzie would move from Pietermaritzburg to Cape Town in search of real and accepting training facilities. The city, in the shadow of Table Mountain, was by this time a thriving metropolis, and McKenzie immediately felt more at home. “Cape Town had a lot of coloured gyms there… I saw the gymnasium where they were training [and] there’s no whites. And I thought to myself, ‘I have to leave Pietermaritzburg now, go and live in Cape Town. That’s where everything’s happening.’” He continued to lift at a level unmatched at home and also, he suspected, abroad.

But McKenzie wasn’t picked to represent the nation at the Rome Olympics that year, or any year after. South Africa was banned from the competition in 1964 and would be barred for two decades in protest of their apartheid policies.

“I was the best weightlifter in South Africa, but I wasn’t chosen. I knew about apartheid, but we couldn’t do anything about it,” says McKenzie. “The hardship side, you remember that very well. That cannot get out of your mind.”

When Nelson Mandela was imprisoned on an island just outside of Cape Town, McKenzie realised he would have to seek his fortune abroad. Despite his incredible strength and consistent success, McKenzie was denied the opportunity to represent South Africa with dignity. On the rare occasion he was invited to travel with the team, the role came with the stipulation he would sleep alone, quartered away from the others. And so, with the encouragement of coach Stent, McKenzie flew to London. His wife and two children would follow soon after, in support of his dream – but not unaffected by the sacrifices it demanded, his daughter Vanessa McKenzie says.

“England was a great escape for him. So we all followed. My childhood was with my mum. Mum was the carer, Dad clearly was being a sportsman.”

In the United Kingdom, free from a society constrained by apartheid, Precious McKenzie was celebrated for his abilities and unhindered by his ethnicity. And just as he did in South Africa, he began to crush records at every weight in which he competed. He had found a country that took pride in his achievements and was more than happy to let him compete.

“I was very happy because I took it this way – here is a country who took me with open arms, not because of my colour, my religion, they took me on for what I was. And that’s why I was so proud of England.”

Across the next 15 years he would win Commonwealth gold medals in Jamaica, Scotland and eventually Christchurch, as well as representing Britain at three Olympic Games. In 1979, he set a 1,339lb (607kg) total while weighing just 123lb (56kg) – a world record he still holds today.

“When dad was awarded the MBE,” Vanessa McKenzie says, “the recognition at that point was, ‘This is real. This is not just my dad doing a sport, going to work’ – he was a force and he was being recognised for all that we missed out on.”

But it was his trip to Christchurch in 1974 that proved most influential in shaping the latter part of McKenzie’s life. In this dour but burgeoning country, he was a superstar; a freak athlete with an exotic brand of charisma, a man who had seen and competed on more continents than most people could name.

“New Zealand was like a magnet to me,” he says. “It caught me and pulled me to New Zealand. I decided ‘if these people love me so much, why shouldn’t I stay here?’ And then the media got hold of me.”

By 1978, McKenzie was 42 years old and on the verge of retirement. But, despite having travelled the world and met the Queen and Muhammad Ali, he had one last item on his sporting bucket list. Grateful for the welcome his family had received in New Zealand, McKenzie decided to compete in one last Commonwealth Games – this time for his adopted country.

Coming into his last lift, and suffering severe cramp, McKenzie found himself in a duel with the Indian weightlifter Tamil Salvan for Commonwealth gold. Despite his age and the immense pain in his screaming muscles, McKenzie lifted more than 200kg, beating Salvan and securing a rare gold for New Zealand in the bantamweight division.

Now in his 80s, McKenzie has never stopped lifting. He trains his athletes – the local residents of a retirement home – as often as six days a week, with the same vivacious personality that captured the hearts of New Zealand almost five decades ago. And though his records remain in the past, McKenzie is content with his achievements, and with the places and people they brought him to.

“My philosophy is stand up to be seen, speak up to be heard… but shut up to be appreciated.”

Scratched: Aotearoa’s Lost Sporting Legends is made with the support of NZ On Air.