As the country counts down to the Joseph Parker vs Andy Ruiz WBO world heavyweight championship fight, The Spinoff presents FIGHT WEEK, an inside look at the life and career of Joseph Parker, culminating in the Barkers 1972 magazine cover story Inside Team Parker on Friday.

Today, Don Rowe follows Team Parker as they prepare for the May 2016 Parker vs Takam fight, IBF eliminator and richest prizefight in New Zealand history.

FIGHT WEEK is brought to you by

After six rounds of padwork, training was called off.

Now in the last stretch of a twelve week training camp, Kevin Barry and his charge Joseph Parker had been working three minute rounds with quiet intensity and focus. The young heavyweight was working steadily, throwing shots to Barry’s padded body and right hands over the top. A blue Underarmour shirt clung moistly to his mountainous shoulders, every movement a branding moneyshot. Parker was tightly coiled, throwing hard but pulling his punches at the last second somewhat, missing the audible snap indicative of a perfectly placed shot.

The pair moved constantly, treading the same circles they have orbited around one another over the past four years, endless kilometres of circling and shuffling and jabbing. Joseph’s brother John stood at ringside, towel and water in-hand, watching intently. Parker barely rests between rounds, always talking, faking, feinting, analysing the previous round and preparing for the next, just like a real fight. Disciplined and tight, his shoulders were high, hands up near his chin. No lazy habits, no resetting between combinations. Ten days out from the fight of his life, Joseph Parker was simply honing the skills he’d learned over the past four years.

But still they stopped, a collective unvoiced decision to call it quits for the morning. After nearly half a decade of work, the team know when things are firing and when they aren’t. Barry and Parker operate on a trust based model and there’s no time for mincing words.

“Three years ago when Kev picked me up to go back to Vegas, he made it clear we’ve got to be very honest with each other,” Parker said later. “Kev said that this would only work if we’re honest about everything, including things like training.”

For his part, Barry saw it coming.

“It’s the bloody media obligations,” he said, stuffing focus mitts and sodden handwraps into a well worn travel bag.

As part of a two week media whirlwind, Parker had spent the morning filming a commercial for Tourism Auckland, set to play ahead of his next bout against French contender Carlos Takam. It was a demanding shoot, requiring skills one wouldn’t normally associate with those required in a champion fighter.

“All that shit gets in the way,” says Barry. “Joseph wants to say the right thing, he wants to show how he’s developed, show he knows what he’s talking about and that he can articulate it well. All that takes energy that I need from him in the gym.”

Parker himself seemed unfazed, as he always does, skipping rope steadily and rapping with enthusiasm to an OT Genesis track playing throughout the gym. “This price is way to high, you need to cuuuut ittt.”

Hidden inside an inconspicuous fiber optics company in industrial South Auckland, the gym is completely invisible from the road. Behind three doors and past a seven-foot tall robot sculpture, it’s a simple but modern affair: one ring, some weights, a row of bags, a round timer and a row of mirrors. The greatest fighters of all time watch from the walls. Muhammad Ali, Mike Tyson and even Kevin Barry’s old rival Evander Holyfield stare out from posters promoting fights from an age of heavyweight boxing long gone.

The gym is owned by Mike Edwards, who also looked on from a folding chair to the side of the ring. “If I had have known you were going to play this rap rubbish, I’d never have let you connect your phone” he told Parker. “Hey, we always train with music,” Parker countered. Behind Edwards, a wall was dedicated to more local champions: David Tua, Shane Cameron, and myriad shots of Joseph, increasingly more muscular and mature, each photo a little closer to manhood.

Parker has finished camp for his own bouts here for the last three years. It’s a sanctuary away from the circus outside, a space solely dedicated to putting the final edge on his skillset, honed over the previous months in Las Vegas, where he has lived and trained with Kevin Barry for the past three years.

In the final days of May, Parker made his way to Mike’s Gym around the same time every morning, weaving through the swarms of trade vans drawn like moths to the glow of the V-branded bakery next door. Joseph always took the wheel, huge even in the captain’s seat of a blacked out Chrysler. Parker spent a lot of time in that car, pulled in every direction by obligations with everyone from Burger King to Jono and Ben. The upcoming fight with French-Cameroonian Carlos Takam would be the biggest of his career, and that was reflected in his ever growing media schedule.

The day he arrived in New Zealand, Parker went straight from the airport to training, worked out for 14 rounds, then shot across town to arrive at Barkers flagship store on High Street, Auckland, slightly after his team, having parked the car himself. Parker was there for a suit fitting – the increased media obligations merit a new look, out with the tracksuits and in with the fitted suits.

Joseph was affable, laughing and joking with everyone, calling Kevin ‘Dad’ and his PA Bianca ‘Mum’. While he was measured and fitted, however, Barry took control of the situation.

Kevin Barry stands close and maintains eye contact. It’s an assertive style, one evident throughout fight week when he consistently front-footed the circling press. His breath smells like gum, and both himself and son Taylor chew voraciously. “When did you start writing?” he asked me. “Who publishes you? What website do you work for? What was your involvement in fight sports? What sort of access do you think you’re getting? 60 minutes wanted to do a special, following around for the last two weeks of camp, I told them it’s not happening.”

When Kevin Barry says no, he means no. Unless the person asking is Sala Parker, that is. And so it was that on a rainy afternoon several days later, Joseph Parker was welcomed on to Mangere East Primary School in South Auckland. The hall was packed with hundreds of kids and more than a few parents, singing in unison as Joseph and John made their way through the crowd to the front of the hall.

“Joseph Parker, our Champion and Future Champion of the World,” read a banner. “Toa o te Ao”

After a short speech, Mangere East’s champion was seated in the Lucky Ducky chair, a rainbow seat adorned with yellow ducks, and plied with questions on everything from training routines to the possibility of a Trump candidacy – easily the most difficult curveball in two weeks of press.

“I visit a school every time I come back” Parker says. “It does feel good that they are there because they want to see me, rather than just being at a press conference because it’s their job. It means more to the kids.”

As much as he loves it, however, every event takes energy away from training, already difficult after a gruelling camp. Leaving the school, Parker waded through a tide of kids grabbing at their hero. His Chrysler, engine running, was swarmed with kids, reaching and clambering and struggling to touch the prizefighter. He drove slowly but inexorably towards the gate, shaking hands, taking selfies, stopping the occasional kid from climbing through the window. It was a hero’s farewell.

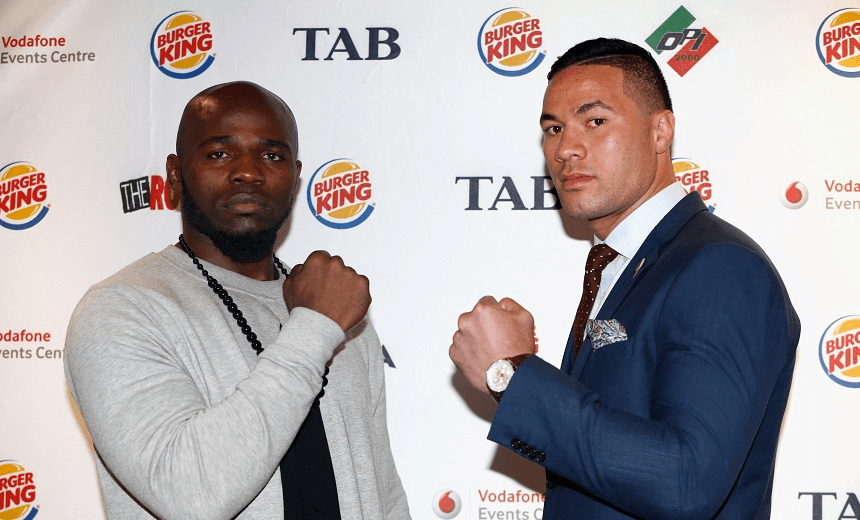

Carlos Takam didn’t have those same media obligations. Surly at the presser, short spoken even through a translator, Takam spent the week keeping to himself and his team, focusing on his training and the upcoming fight. When journalist Duncan Johnston asked him about sparring with Parker’s rival Junior Fa’a – a supposed secret – Takam’s attitude changed permanently. At the weigh-in he refused to talk to the press at all, angered by the typical questions about rugby and “isn’t New Zealand beautiful” and “what’s your favourite part of New Zealand” that all visitors endure. Takam was in New Zealand for one reason, and it was to ruin the party for Parker and the boxing faithful.

On the night of the fight, as the suits took their seats below the big screens, an ad showed Joseph Parker flying high above Auckland in a float plane, performing for the camera, acting and promoting just hours before a training session that would ultimately be called off after six rounds ahead of the most important bout of his career.

The fight was two hours away.

Read FIGHT WEEK part one: A chronicle of Parker’s amateur experience and transition to the professional prizefighting ranks

FIGHT WEEK is brought to you by