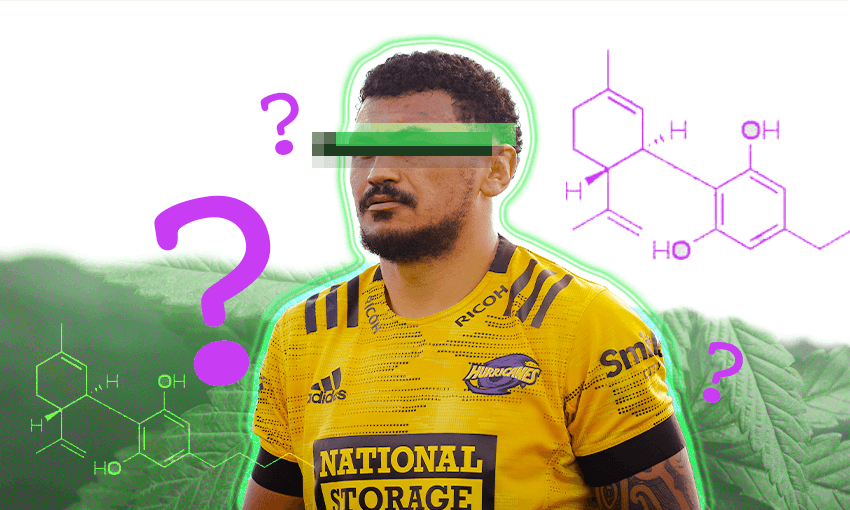

Earlier this month, rugby player Isaia Walker-Leaware had to attend a substance abuse rehab programme to lessen his suspension from sport after testing positive for THC. International anti-drug rules in sport are largely to blame.

Isaia Walker-Leawere is a professional rugby player for the Hurricanes, Hawke’s Bay and the Māori All Blacks. He has also, on at least one occasion this year, used weed; a routine in-competition drug check in May this year showed the presence of THC, the active ingredient in cannabis, in his sample.

How did the New Zealand Rugby Judicial Committee react to the THC test? It followed official guidelines: Walker-Leaware and his team were offered two options for the 26-year-old: either be banned from sport entirely for three months, or be banned for one month and complete a substance abuse programme. The ban was backdated: by the time the details were announced, on August 5, it was already over. But he still had to complete the substance abuse programme after smoking weed “to wind down” one evening and taking a drug test three days later.

Walker-Leawere is one of only a few New Zealand athletes who has tested positive and been sanctioned for use of recreational drugs. According to Drug Free Sport New Zealand (DFSNZ), only 30 athletes have violated anti-doping standards in the last five years, and only five of those for recreational drug use: three for cannabis use, one for MDMA and one for methamphetamine.

Cannabis is widely used in New Zealand. Nearly 95% of the respondents to the latest New Zealand Drug Trends Survey said they’d tried the drug at some point during their life; 74% had used it in the last month. The 2020 referendum on legalising recreational cannabis had 48.4% of the electorate in support of the measure, and cannabis for medical use is available by prescription. Yet despite this, the drug is still on a list of prohibited substances for athletes.

DFSNZ advocates for a clean competition in all disciplines, at all levels, throughout the country. They’ve been pushing for an “athlete-centred” approach to cannabis use – including removing it from the prohibited list – for two decades.

“Our internal research, external advice and wider consultation with the medical and sporting community in Aotearoa New Zealand has provided no evidence that cannabis is performance-enhancing,” says Nick Paterson, DFSNZ’s CEO. “Getting Mr Walker-Leawere substance abuse support and back into sport after serving his sanction is the most practical outcome and supports long-term athlete health and wellbeing.”

New Zealand’s sporting drug rules are derived from the regulations issued by WADA, the World Anti Doping Agency. Formed in the 1990s, the organisation has banned cannabis since a Canadian Olympic medallist snowboarder tested positive for THC in 1998.

Paterson explains that WADA has three principles that govern which substances are regulated: performance enhancing, health risks or being against the spirit of sport. The organisation has agreed that cannabis use falls into categories two and three, and says that since the jury is out on category one, then cannabis will remain banned. Whether a drug is widely used or legal in the athlete’s home country isn’t relevant to WADA regulations. Only WADA has the power to remove the drug from the list.

Walker-Leaware is not the first athlete to discover this regulation the hard way. In the 2020 Olympics (held in 2021), American sprinter Sha’Carri Richardson was banned from competing due to a positive THC result after she’d successfully qualified for the American team. Like Walker-Leaware, she was banned from competition for one month. She said that she’d used cannabis to cope with the pressure of the Olympics at the same time as a family member’s death. The US Anti-Doping Agency said that they couldn’t change the rules, as they had to comply with the regulations of WADA.

Following outcry over Richardson’s ban, WADA revisited the cannabis restriction, but said in 2022 that the regulation would remain in place, as cannabis use violates the spirit of the sport. The organisation also cited scientific studies, saying that it remained in doubt whether cannabis enhances performance. Scientists have criticised this conclusion, saying it’s out of date: evidence suggests that if cannabis has an impact on performance at all, it’s a negative one, as it slows response times.

WADA, DFSNZ and the host of other organisations that operate in this area are always treading a strange line between what should be allowed and what shouldn’t be allowed – and what can and can’t be detected. For instance, caffeine and alcohol are widely used drugs that aren’t tested for, even though caffeine can improve performance, and alcohol (promotion of which is deeply intertwined with New Zealand sports) can be a health risk for everyone, not just athletes.

Lots of athletes drink “sports drinks” like Powerade – many of them help to advertise them – that are carefully engineered to have energy (in the form of sugar) and other science-sounding words like “electrolytes” which are supposed to help the athlete perform better. It helps that sugar water has never been a banned substance (unless it contains off-the-charts levels of caffeine and is marketed at children) and that Powerade has, well, the power of the Coca-Cola brand behind it.

Good equipment enhances performance, as does being paid fairly; increasing equitable access to time and space and equipment for all communities would certainly be in line with the spirit of sport principle. But income inequality can’t be detected in urine tests – and so organisations promoting fairness in sports focus on drugs instead.

Doping, which refers to all of the many ways medical interventions can be used to cheat in sports, is undoubtedly more widespread than the number of athletes who are publicly condemned for it. Between 1-2% of samples assessed by WADA reveal banned substance use, but randomised self-reported assessment estimates that as many as 43% of athletes dope. Many of these substances are difficult to detect, as is blood doping, where athletes are given their own previously extracted blood to increase endurance. But THC (and the cannabis use it indicates) stays in the bloodstream for multiple days, is easy to detect and, despite evidence suggesting it’s unnecessary, remains on WADA’s banned list.

Incredibly, Walker-Leaware is lucky to have only received a one-month ban and compulsory rehab. Three years ago, he would have been facing a multi-year ban, all for a few puffs to wind down.