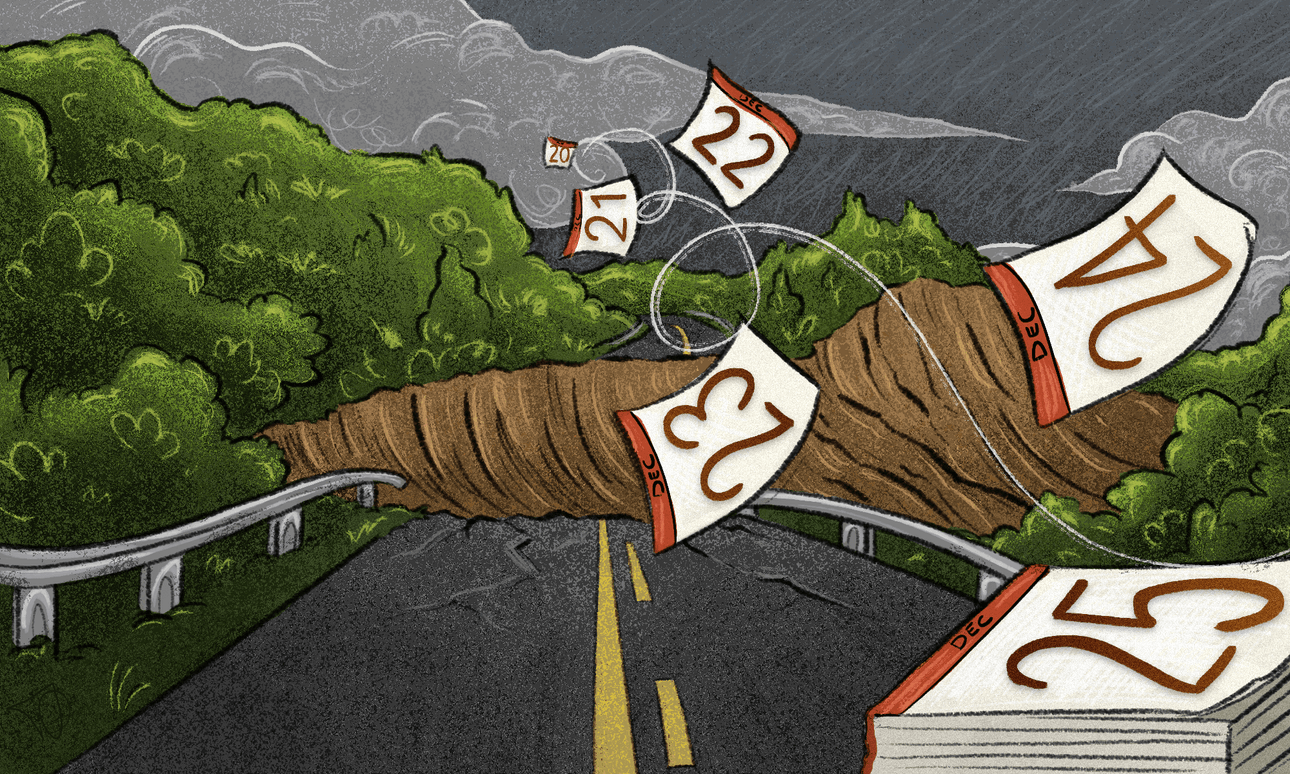

When we chose to live in the Coromandel, I never questioned the permanence of the road in and out.

The Sunday Essay is made possible thanks to the support of Creative New Zealand.

Illustrations by Tyler Downey.

November 2022. We’ve finally bought outdoor furniture to replace the worn-out rattan chairs we dragged out onto the deck when we moved to Hikuai four years ago. The kids take immediate ownership of the gigantic furniture boxes as we unpack. They try them down the steep sides of the hill, disappearing from view with unbridled joy.

As we assemble the couches, we discuss what sort of people we’re going to be: will the cushions come in every night, or will we leave them out? What will we do when the wind whips up and threatens to hurl even the heaviest furniture into the windows? What if it rains sideways under the eaves of our deck?

November 2022. I can pinpoint the pre-summer optimism. Atmospheric rivers weren’t yet front of mind. Year-to-date rainfall wasn’t being measured in metres. We weren’t rattling off figures like “a whole month’s worth of rain in a day”; “a whole year’s worth before we’ve even hit the halfway mark.” We hadn’t factored in relentless heavy rain warnings bookmarked by cyclones, with more rain chasing after.

November 2022. We agree that we’ll bring the cushions inside. Moot point by the end of January: due to the wet, those couches have pretty much become permanent features of the lounge. Meanwhile, a section of the Kopu-Hikuai road, our way out of the Eastern Coromandel to Thames, Auckland and Hamilton, is crumbling under all the wet.

It’s easier to explain where Hikuai is by describing its proximity to the much more familiar destinations around it: it’s not far from Whangamatā, close to Pauanui, on your way to Tairua.

There’s not much out here but farmland and lifestyle blocks, a petrol station and country school. There are relics of the goldmines to explore, a DOC campsite under the shadow of the Pinnacles, and a few decent swimming holes. Oh, and it rains a lot.

We were warned about the rain when we were first looking to move up here. But we had been living on the flat in Wellington, where every downpour formed a lake at the bottom of our road. The wind tunnelled through the house and up through the floorboards. We’d lost several heads of broccoli to the Easterlies. We were used to living with a lot of weather.

But here there’s a different rhythm to the rain. Every year we’ve been in Hikuai, there have been a few decent floods. Relentless heavy rain all night, waking up to the valley’s paddocks becoming vast lakes; water spilling out of the riverbeds, across the roads. Those who grow up here say it’s always been like this, but as newcomers we were in awe of its alluvial nature; the speed with which it filled up the valley, then drained away when the rain eventually stopped.

At the start of this last extraordinarily sodden summer, we were on a regular trip back from Thames with a bootload of groceries. My six-year-old started to count the long tails of cars exiting the Coromandel early as we turned onto the Kopu-Hikuai. She counted 600 before we turned off the highway; a constant stream all leaving ahead of the first cyclone of the season and its forecast dump of holiday-disrupting rain.

Another day, returning from another supply run across the Kopu-Hikuai, we were slowed by stop-go traffic controllers midway through the gorge. As we slowly crawled past, I noticed several men in hi-vis jackets walking slowly along the roadway on the west-bound side. They were all looking down at their feet, at the cracks running parallel with the roadway, a gap that looked about a foot-width apart.

A group chat I’m in with some other local mums filled with nervousness about the road and speculation about what happens next. Someone suggested we could use super glue. Our most immediate exit off the peninsula was restricted to controlled, one-way traffic over the cracks; daylight hours only. Wryly we suggested this was so the road workers would notice the unlucky one whose car fell down when the road did.

We googled “severe rotational slump,” which is as bad as it sounds. I add “slump” to my lexicon describing the myriad ways roads can become unusable. See also: car accident, flooding, rockfall, landslip, landslide.

We knew there would be trade offs when we moved here five years ago. The draw of getting our hands into the dirt meant we had to hang up our bicycle helmets and resign ourselves to owning a second car because of all the extra driving. We said goodbye to a bustling local fruit and vegetable market in favour of a place with space to grow our own. We moved further from friends but closer to grandparents.

Here, the kids are expert tree climbers. They bring fistfuls of wild flowers indoors. They look carefully at the mushrooms sprouting in the shade. They find pieces of cardboard for sliding down hills. One set of grandparents is close enough that they pop in for a coffee on their way home from appointments in the city. Another set is further away, but close enough they can visit for lunch.

When we first looked at this piece of land and pictured moving here, we were trying to figure out what was next. The skies were clear and the view over the river plain to the Pinnacles was spectacular. We thought about this place we’d always driven past, and the more we talked, the more we convinced ourselves it was still close enough to the big city stuff we weren’t quite ready to give up.

When we chose to live here, I never questioned the permanence of that road. I never gave it a minute’s attention.

In February, Cyclone Gabrielle piles water and debris onto the already-sodden ground and everything everywhere starts to crumble. As we return online after several days with no electricity and limited internet access, we’re stunned to see reports coming out of Tairāwhiti and Hawkes Bay, and the refrain we hear from everyone in our community is how lightly we got off by comparison.

Our region didn’t escape the damage, of course, but its mostly the roads that have been hit. On another pouring day, I sit mindlessly scrolling images from a road status group until I’m almost out of battery. Another piece of highway disappears into a gaping hole. “I’m not looking anymore,” I message a friend. “I just can’t. It’s not healthy.”

For a few days Hikuai is at the end of the road. We’re not far off being an island.

It sits uneasily, geography shifting beneath you. The view out the windows doesn’t change, but it’s fundamentally different, like moving to a new town without taking a step. It’s not exactly anxiety, more a bone-deep fatigue born of having to re-adjust all the minute details of life. I spend hours on the phone cancelling appointments and readjusting plans, apologising for the chasm between us and the places we’re meant to be.

Without warning, we’re almost two hours from the nearest hospital. It feels disturbingly far. Eyes are on the kids a little bit more, letting them jump but reminding them how far we’d have to drive if something goes wrong. We hope we can catch them before they hit the ground.

My youngest is an extremely tactile three-year-old, always running her hands along the walls. I catch her touching the door hinges as she walks into the hallway; I imagine the wind blowing through and slamming those tiny fingers. I try to explain why we don’t touch things that can close and pinch, but she meets my words with a three-year-old’s mix of disbelief and defiance.

It’s a shock, but not a surprise, when a tiny hand is jammed into a car door hinge late one afternoon. We’re at a local school and I’m awed by all the help that surrounds us immediately, a first aider coming with a tub of supplies, a crowd of kids sharing their own tales of cuts and blood and injury. My girl’s hand is wrapped up in a tight ball to keep it closed over a gash, and we drive to get an X-ray and treatment. I sit in the back seat, holding her hand up and holding her close. She talks about how sore it is. Hospital is a long way away.

Before a timeline for the road rebuild is announced, local Facebook groups are alive with reckons about alternative routes through old forestry roads, temporary roads and quick fixes. The armchair engineers and roading experts pitch in. I understand the frustration of those who are certain there’s a quicker path through. There are people still living here who helped build the original road, who’ve worked this land for years. The local economies are built on tourism and that tap has turned down to a trickle. We’re not immune to speculation, pulling down the topo maps and trying to find reassurance in tiny lines of forestry tracks.

Our household wonders what timeframe would be too much for us. Is it going to take two years to rebuild? Three?

When we moved here, we were told it would take decades to become locals. There are generations here, families who are intimate with the history of this area. We’re still so new, in this local measure of time. We’ve only just cleared the gorse and bought outdoor furniture.

We’re in the lucky position of being able to wait it out. Both myself and my partner work remotely. One of our kids doesn’t do well on the winding roads to the north or south, but we can take our time when we need to travel. The dentist can wait. We can fly from Tauranga instead of Auckland. We don’t need to be in Hamilton or Auckland with any urgency or frequency.

Plenty of people around here can’t opt out of travelling for work, school, medical appointments or family. With that one road out of action, what was a 40-minute drive each way has become a four-hour round trip. A smooth 1 hour 40 minute trip to Auckland Airport now takes three hours each way. It’s suddenly a hell of a commute.

In early winter, we get a better sense of when we might return to normal. A bridge will be built to span the gap, completed within a year. A year in this altered state seems in the realm of manageable for our family. Less so for those who have businesses or rely on tourists in the local towns: it’s another blow after the wet summer, preceded by the Covid years. But a year is better than two, three or more.

Spring is chased by a thick buzz of rumours about the possibility of the road being re-opened early. It’s been dry enough, the crews have worked incredibly swiftly, it’s almost done. Speculation bounces around for weeks, but one night a wave of virtual cheers permeates our group chat. It’s official: we’ll have a new bridge for Christmas.

Who we are is shaped by the places we go, and how long it takes us to get there. For those of us on the Eastern coast, it’s not long now until we can visit those places again.