The Royal Commission of Inquiry into abuse in state care has prompted many to reflect on they way things were. Former child psychologist Lynn Jenner writes on the time a former colleague was convicted of abusing a client.

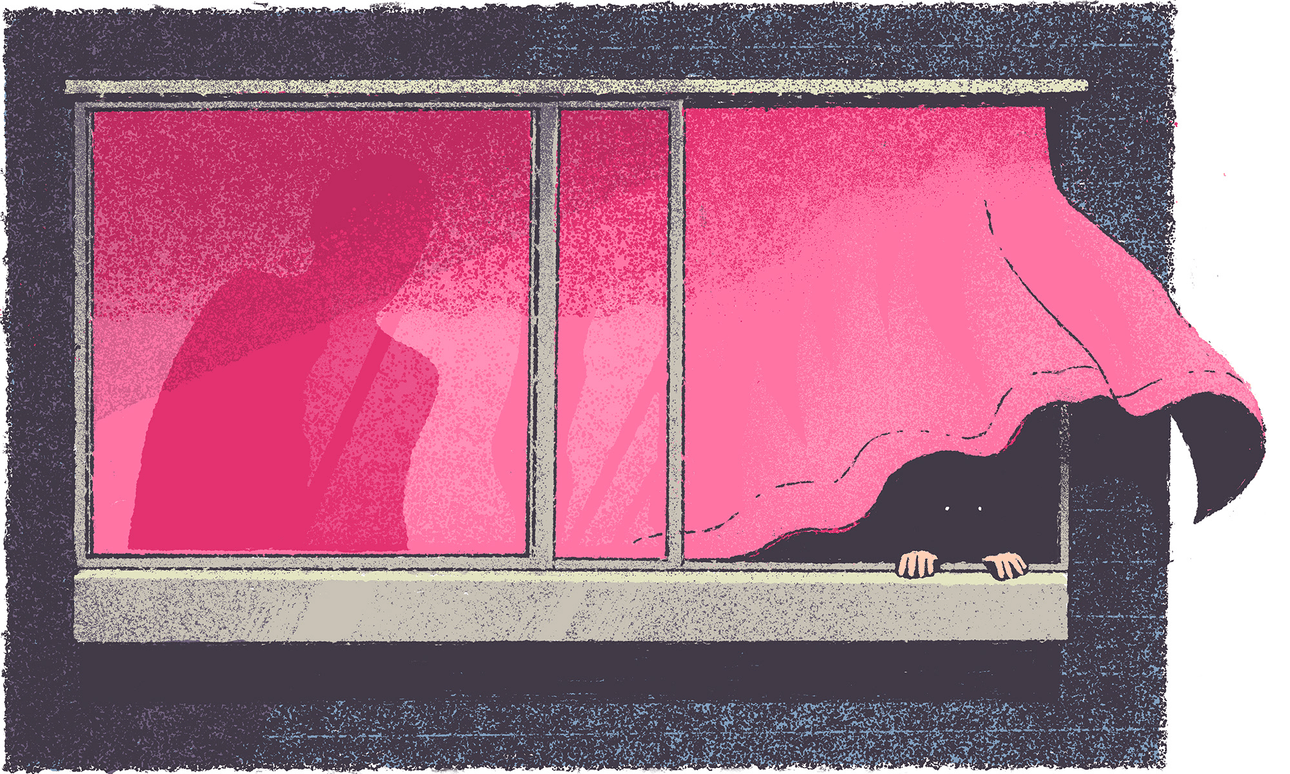

Original illustrations by Wwowly.

The Sunday Essay is made possible thanks to the support of Creative New Zealand

Content warning: This piece contains descriptions of child sexual abuse and workplace harassment.

The Abuse in Care Royal Commission of Inquiry has brought up traumatic memories for hundreds of former state wards. We’ve heard so many of them testify in Auckland, and hundreds of others are doing so behind closed doors. But these people are not the only ones looking back.

I have also been thinking about my own time as a young psychologist in the 1980s, in particular the time when a boy fell victim to one of my former colleagues.

Later, in 1992, the psychologist — let’s call him Joe — was found guilty of abusing a 12-year-old boy. Joe was sentenced to two years imprisonment. The victim had been 12 when the abuse occurred, and 15 when the case went to court. Today, assuming he is alive, he would be in his early 40s. It is possible that the actions of my colleague have cast a long shadow over his life. If I could, I would like to send that man some kind of telepathic apology for what happened to him in the name of psychology. I’ve heard victims saying that apologies don’t change anything, and they are right. But looking into the circumstances that allowed the abuse to happen might help stop it happening again.

My colleague did not deny the particulars of the charge, which had to do with the fact he had masturbated the boy. But he denied this constituted indecent assault. He argued that he was teaching the boy muscle relaxation. He said masturbation was a proper treatment for this boy’s sexualised behaviour problem.

In the trial, the victim gave evidence that what happened had confused him. The boy’s father also gave evidence that he had not agreed to this form of purported therapy. The judge accepted the opinion of John Smith Williams, a psychologist with the Wellington Area Health Board, that “the treatment embarked upon by the accused was not justified and amounted to a form of abuse”.

Even though his name was suppressed during the trial, I knew as soon as I read about the details that this was my former colleague. Back in the early 1980s, when he and I worked for the Department of Education Psychological Service in Dunedin, he had used “muscle relaxation” as a treatment for boys who stole. Some colleagues, myself included, thought the way he went about this was … well, unusual. Today I am 66, a writer for the better part of two decades now, but educational psychology was my first career and I loved it with all my heart.

The court case raised a lot of questions for me. Had this man been sexually abusing boys for years right under our noses? Were there warning signs we had missed? Was Joe always teaching masturbation as a muscle relaxation? Did it start in good faith and then drift into abuse? Was Joe sufficiently naïve (or arrogant) to think he could touch a client’s genitals with impunity?

Food for thought in 1992. Today it’s a full-scale political meal. The Abuse in Care Royal Commission of Inquiry, the country’s largest and most-expensive ever, is investigating the galaxy of ways people exploited their positions of power in care facilities in the second half of last century. There’s a lot to talk about.

Back in the early 1980s, around 10 of us worked in that Dunedin office. Our job mostly involved helping teachers and parents of children and young people with disabilities or learning and behavioural problems. We assessed children’s reading or maths. We worked where needed with educators on their class programmes.

These were still the days of a highly centralised public service. The Psychological Service offices had a similar East German look everywhere: the same chairs, the same desks, the same pens; all procured under the same guidelines. The way we practiced was not so uniform. We had latitude to create our own version of educational psychology. For me, that was attempting to improve the environment in the old state-run boys’ and girls’ institutions. In Joe’s case, he was interested in finding ways to stop adolescent boys stealing.

The boys my colleague worked with would come to the office after school. The treatment took place in a room with pink curtains. The curtains were always closed. I noticed this because working with young people in the office was unusual for me and most of the others.

Joe and I were not close. He had a senior role, with responsibility for liaison with the educational psychology training programme. I met him when I was a first-year trainee. When I asked him to reconsider an essay grade and offered my rationale, the conversation quickly became heated. He possessed an assertive manner and radiated physical energy. I, on the other hand, was in my mid-20s, slightly overweight, not particularly confident.

A year on, I was rostered to shadow Joe for a couple of days as he worked. We went in his car to a sheltered workshop and a special-needs school for children with severe intellectual disabilities. I remember his comment that I didn’t need lunch because I could metabolize stored fat. That was the only time I was directly involved with him in the couple of years I worked as a psychologist in that office. Another time I was walking along the corridor to the tearoom and, as I passed that internal room whose curtains were always closed, someone made a crack about how Joe’s clients were all boys of a certain age. The tone was half-joking, half not. None of us did anything except drink our tea, but I remembered that moment through the years.

Sexual abuse had not been mentioned in my training. In subsequent roles I held with the Department of Social Welfare, I became a specialist in the field of family violence, but that was later. Even so, I knew from being a woman that some men are not safe to be around. I also knew that having many boys of a similar age as your clients couldn’t happen by chance. You would have to make it happen. Deliberately.

I assumed the theory behind Joe’s “intervention” was something like this: The boys who stole might be in a heightened state of stress, perhaps because of emotional and family issues. This would lead to them having a racing heart and shallow breathing and other physical signs of stress in the body. A state of high arousal, as a psychologist might say, meaning the “fight or flight” mechanism was activated.

I imagined that if a person stole while in this stressed state, the stealing would be part of a pleasurable high. Even exciting, perhaps, as violence can be. Maybe they would feel more relaxed after they stole, and this would also be part of the pleasure. I assumed that Joe was teaching the boys to de-stress by using muscle relaxation, so they would not be in that aroused physical and emotional state where stealing would be fun.

In a sense, I suppose, Joe’s interest in relaxation reflected a time in which TM, yoga and massage were all the rage. For adults, there were machines that showed your brain waves and researchers found that by watching this display, people could learn to make more of some kinds of waves and less of others. This was called biofeedback. From a psychological point of view, the idea of teaching someone relaxation as an alternative to stealing seemed reasonable. It wasn’t the use of relaxation that made me uncomfortable. It was the procession of boys in their grey school jumpers and the closed curtains.

Part of the evidence presented to the court in 1992 was that Joe had told the boy’s father he would touch his boy’s stomach and legs, but not that he would masturbate the boy. In 1989, when the ‘treatment’ took place, every psychologist knew, as they do today, that informed consent meant the person agreeing to treatment, in this case a father on behalf of his son, had to know and understand what was being offered. Assuming that what the boy’s father said is true, Joe either made a serious ethical mistake, or deliberately concealed his intention to touch the boy’s penis.

The boy’s father also said in court that he was not present during the treatment sessions.

Thinking too much about what this father could have done differently is not helpful or even fair, in my view. Parents shouldn’t have to do all the work to protect themselves and their children. Parents should be able to assume there are other safeguards, like the use of informed consent. The problem is, if you are a parent, how do you know you have not been fully informed? You can’t. That’s why other protections are needed.

Despite all my experiences with children who had made allegations of sexual abuse, the 1992 court case was the first time I knew an alleged abuser. It was also the first time one of my psychologist colleagues had been found guilty of sexual abuse. Through my contact with the New Zealand Psychological Society, I knew of cases of sexual relationships between therapists and their adult clients, but no cases involving children or young people.

In 1992, I still saw psychologists as lambs in a meadow. Outside the fence, people were various mixtures of good and bad, but inside we were part of something innocent and virtuous. Well, sort of. There was a colleague who touched my bottom whenever he passed me in a confined space. One day I had enough. The next time he touched me I said, “I decide who can touch my bottom, and you aren’t on the list”. The man looked … well, if not like a lamb in a meadow, then sheepish. It never happened again. Another colleague once barged into my bedroom, pushed me up against a wall and squashed his beard into my face one night when we were on a live-in course. He was a bit more frightening. I didn’t tell anyone about that incident for 10 years. I had probably heard the term “sexual harassment” in the 1980s, but I thought the way these men acted was my problem.

There were colleagues who were a wee bit crazy and some who were depressed. There was me, learning the job by doing it, and growing up at the same time. I cultivated marijuana in my basement, didn’t pay my bills and my private life was not altogether respectable. Clearly, psychologists were just like everyone else. But remnants of that pride in being part of this profession and trust in its people still existed in my mind.

As I read and re-read the report of the prosecution, I realised that from the day of the guffaws in the corridor with my friends, I kind of knew what my colleague was doing back then could be problematic. And yet, at the same time, I never knew exactly what he did in that interior room. I had a good idea of what some people in that office were up to, because I worked with them or talked with them. But I didn’t know much about this particular colleague’s work, nor did I try to find out. I think of my response to Joe as an unspoken withdrawing from him and his work. I don’t think what I did is the same as turning a blind eye when you know something is wrong. What I did was less self-aware and more about protecting myself.

According to the 1980 code of ethics of the New Zealand Psychological Society, if I had concerns, I had an obligation to “take steps to bring the matter to the attention of those charged with the responsibility to investigate it”. But having seen something that did not seem quite kosher, I did nothing.

If I had encountered this situation later in my working life, I think I would have known enough to allow those warning signs to rise up from the semi-conscious murk and form themselves into words. Once I had some words, I might have been brave enough to have raised the concerns with my boss. He would have had to decide what to do after that.

So why didn’t I act? I think in those first few years I was swamped by the complexity of the job. When you are out of your depth, it is hard to see what is important and what is not. My junior status in relation to the colleague in question was also a factor.

The final sting in the tail happened just last year. When casting about for information about his conviction, I discovered a 1985 publication in Joe’s name. The “treatment manual” is a photocopied typescript with no ISBN number. Nevertheless, it’s in the National Library collection online catalogue. Where we once worked together appears on the front, and, on the strength of that, the Department of Education Psychological Service is listed in the catalogue as the publisher. I didn’t know about this manual in 1985. I was living in Auckland then and about to have a baby.

The treatment outlined in the manual relies on substituting a socially acceptable reward for the reward of stealing. If the client finds stealing sexually arousing, it says, the therapist should teach him (my emphasis) to replace that with other sexually rewarding behavior, in this case masturbation. In this situation, the manual says, the therapist should:

“Arrange for sex information to be given to client and ensure client is taught to masturbate using appropriate imagery. Use ‘self-monitoring’ and reinforce client for increasing duration of erection and frequency of attempts to masturbate to orgasm … However, it is as well to ensure that the client is using appropriate imagery. The client is encouraged to use Playboy nudes etc. as reinforcers.”

In the context of the later conviction, the words “ensure client is taught to masturbate” leapt out of the text, as does the fact that the envisaged clients were all male. The manual is about stealing and that is different from the sexualised acting out behaviour at school which was the referring problem for the boy in the court case. But when masturbation crops up in the treatment of stealing and in treatment of sexualised behavior, it starts to look like a modus operandi.

A computer-search of the time reveals that masturbation was definitely not a commonly accepted treatment for adolescent boys who stole. In the culture of the public service, I would have expected some scrutiny of a document that was going to be in the public arena, carrying the department’s name.

I’m sure it should have been obvious, even in 1985, that it was risky for a psychologist employed by the public service to advocate teaching boys to masturbate. (I’m leaving aside the question of what is “appropriate imagery” for teenage boys to masturbate to, because that opens up a whole other piece of social history.) It would have been generally understood that a government-employed psychologist who taught adolescent boys to play with themselves was a reputational risk to the department. Just the word “masturbate” in a news item would have been politically embarrassing.

In those days, there was also an assumption that false or mistaken allegations could easily happen. According to that view, a psychologist who is alone in a room with an adolescent and teaches an adolescent to masturbate, puts himself at risk. The psychologist might be wrongly accused of sexual abuse, and he would have no witnesses to support any denial.

Most importantly though, I would have expected that any person who read the stealing treatment manual would have seen that treatment which involved masturbation was a risk to the client.

I would like to think that a psychologist whose work was drifting in this dodgy direction would be spotted earlier now. In the early 1980s, our work was lightly supervised. There was no formal structure of managerial supervision. We entered our vehicle mileage on a form to claim expenses, but we did not have to say what we were doing with each client. Nor was there an obligation, or even an opportunity, to take part in clinical supervision where you discuss your work with an experienced peer. Clinical supervision was nowhere on our horizon.

These days I would expect that a psychologist who was carrying out research using adolescents as subjects, and publishing the results, as Joe was, would have taken the research to an ethics committee. No ethics committee would approve a psychologist masturbating a client, of any age, under any circumstances.

By the time I left psychology it had become the norm for lessons from complaints and prosecutions to be published as part of ongoing professional education. I am not aware of any attempt by the department to use the 1992 conviction to educate psychologists about risks to clients.

Three decades after the conviction, protecting children from professionals who have strayed into some form of abusive or unsafe practice remains a problem — and the subject of sometimes volcanic public discussion.

Protection of children from sexual abuse by professionals is made up of layers. The individual practitioner has responsibility for their own participation in ongoing professional development around professional ethics and safety for clients. The organisations for which professionals work are responsible for ensuring that managerial and clinical supervision happens, as opposed to just being part of policy. The New Zealand Psychologists Board and the separate Psychological Society both offer channels for complaints from clients. In addition, psychology training providers include discussion of power and its relationship to abuse, and community groups and schools help by providing safety education programmes for children and parents.

All of these have evolved somewhat since that earlier time. When I look back on the situation that led to the conviction of my colleague for indecent assault, hardly any of these layers was present.

Still, I’m left with questions.

What might have happened if I had the guts to ask the boss if he was comfortable with what was going on in the room with the pink curtains pulled, and if he had the guts to find out. And how many boys did this happen to? It’s too late for me to do anything, but it’s not too late for others to question any professional about their practice. Even if they are senior members of their own profession. Even if they are colleagues.

After the royal commission has finished with investigating historical faith-based operations and state institutions, maybe it will be time to look at the culture of the public service as it once was and possibly, who knows, still is. And how, specifically, the professions involved in care of children and young adults can not only help prevent abuse, but sure they are never a party to it.