My nose had serious form, history and family connections. But a surgeon made an executive decision to steal it and give me a Hollywood nose in its place.

The Sunday Essay is made possible thanks to the support of Creative New Zealand.

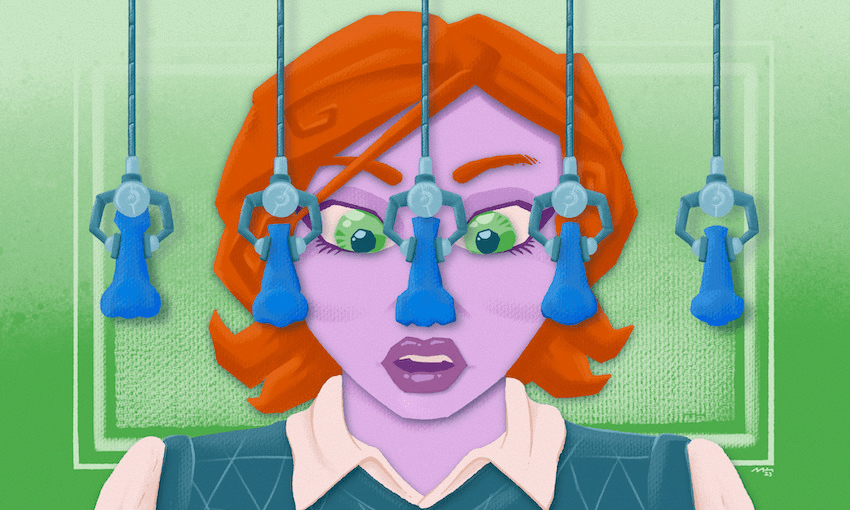

Illustrations by Guy Moskon

My nose got stolen from me last year.

It was a bumpy thing, wonky and ridgelined. I always liked it until learning that I wasn’t supposed to. If I was a dog, I’d be a borzoi – long Slavic snout, curly hair, odd yet delightful, and constantly on TikTok.*

In high school, my nose got bonked up real bad. It was collapsing from the inside; if you gently touched the crest of my hump, you could actually feel a hole sinking into my nasal canal. Aesthetically, it wasn’t noticeable. Physically, I could not breathe through it. Breathing through my nose was like trying to suck custard up a straw. In nightmares, my honker caved in completely, a spelunking adventure gone wrong. After a pleading letter to ACC, I slid into a surgeon’s office for a funded septoplasty.

A septoplasty is a surgery to fix up your septum, the wall inside your nose which divides your nostrils, AKA the bit which bisexuals get pierced. My surgeon was a brisk and gangly man, the kind who takes stairs two steps at a time. He mm-ed and ahh-ed inside of my nose, beaming a dinky wee torch up into my brain.

“We’ll get you fixed right up,” Dr Proboscis said, having assessed the damage.

“Fank yew,” I said nasally, his fingers still pinching my nose. He withdrew the torch and peered at my profile.

“Would you like a free rhinoplasty too?”

“A nose job?”

“Yes. I could take off your nose hump. It won’t take long, since I’ll already be in there.”

I imagined him rummaging around in my nose, skin flipped inside-out like a sock. Put yourself in my place. If somebody offered you a free nose job, would you turn it down?

You could have any nose in the world. I love The Sims, and it was tempting to have a play on my own face. I said I’d think about it. He gave an exasperated huff.

“Well, you could look like Kristen Stewart. But you can keep your hump if you want.“

Did I want? I spent a week deliberating. I Photoshopped my nose and stared at the girl on canvas. She was pretty, but wrong in an off-putting, uncanny way which heebied my jeebies. She wasn’t a girl I knew. Nauseating guilt roiled in my stomach at the idea.

When Dr Proboscis called, I was on the toilet at uni, desperately trying to hold in a plop.

“I have decided to keep my nose,” I said in my most businesslike manner.

“What?” said a woman in the cubicle over.

“If you say so,” responded Dr Proboscis. He sounded peculiarly disappointed, considering it’s my nose, not his. I wiped my arse and left the toilet with a glow of self-love, feeling pleased and true to myself.

The septoplasty was my first ever surgery, peak mandates, and I had to go alone. I was suddenly very young and small. A nurse tried to console me. We discussed her primary-aged son’s Fortnite addiction. She gave me a pre-surgery benzodiazepine. I noticed the phrase “partial rhinoplasty” on my consent form. I didn’t see Dr Proboscis before surgery, but I was assured that my nose would look entirely the same afterwards, and it was purely medical. It is important to keep my dorsal hump, I said, again and again. If they had to fix parts of my cartilage, they promised to build up, not down.

I lay on a table. I touched my nose. Cragged like the Tatra Mountains. Strong, arched. If I ran into a wall, I would leave a nose-shaped hole, schnoz perfectly intact. I blinked. I was in post-op.

“Your nose is beautiful now,” Dr Proboscis babbled at me. “It’s the best nose I have ever done. I shaved a bit off the top. You are going to love it.”

“Euuuruuuughh,” I said, and fell asleep in a pottle of yoghurt.

Recovery was a haze of painkillers and delusions of being waterboarded. I rarely slept, and when I did, I’d awake choking on clots. After a week, I was able to rinse out my sinuses with saline. I waited with perverted anticipation. I hoped it’d feel disgustingly delicious, like hitting your ear’s prostate with a Q-tip. I imagined the saline’s pressure building up behind the dam of gauze, building, and then exploding, chunks splatting across the room, sweet relief of airflow in my nostrils. It didn’t feel that good. It hurt.

Mostly I sat in my bed overlooking George Street, feeling like the ghost of a haunted Victorian child locked in an attic. Mother, when may I play hoop and stick with the other children? The bags beneath my eyes swelled purple, like overripe fruit. My face sallowed bile-yellow. I felt beautiful and frail, lounging languidly while sucking on ice blocks. I watched cartoons and gobbled up Naproxen like Cheerios.

I wore a little condom thing on my nose to protect it when I went out. Eventually I was allowed to remove it, although my nose remained fat and swollen. I have a photo of me at a vampire-themed party around this time — I’m wearing a nun’s wimple with blood-red contact lenses, and my nose is large and orange as the Ohakune carrot. I do not look like a Twilight heartthrob. The nose started shrinking after this, and I was very pleased with it.

But then it continued shrinking.

Oh no, I think. I am transforming into a Whoville resident. It gets smaller and smaller, and I become more and more panicked. I am running out of nose. I would frantically ask friends if it looked different, and they’d tell me it was fine, wondering when I’d be booking my medical breast augmentation or ACC-covered Brazilian butt lift. After a few months, my nose settled into what it is today.

I will describe it to you. It’s a decent nose. It isn’t ski-slope concave, nor does it protrude much outwards. Suddenly I am the default nose when creating myself in video games, no longer pecking hungrily at inaccurate dorsal crumbs.

On one hand: Boo hoo, no big deal. It’s not even a blip in the macrocosm’s radar of things that matter. Quit being so self-pitying.

On the other hand: Give me back my fucking nose, you bastard!

I am not Kristen Stewart. I am somebody who was so, so lucky to have my nose.

It was a symbol of furiously enduring love and survival.

Our nose was once a ticket into a horrible club called the Untermensch – the “undesirables”, the “masses from the East”, Jews, Slavs, Roma and more, those racially inferior in Nazi eyes. If you had eastern blood, a fat honker and dark curly hair, you were in trouble. (Source: KL Auschwitz Seen by the SS, by the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum.)

My Dziadzu (grandpa) is from a small town east of Poland. Although it’s existed since the 8th century, its Wikipedia only has one subheading under History: World War II. It details the massacre, mass graves, Jewish ghetto, the liquidation.

Dziadzu was evacuated from Poland and carted throughout the USSR, eventually growing up in a refugee camp at the base of Mt. Kilimanjaro in Tanzania. He was ridiculously strong – and physically, too. His hugs squeezed the wind out of your lungs, leaving your feet dangling off the ground.

My Babcia (grandma) doesn’t like discussing the war with me, but she alludes to being taken and raised in a Nazi-run orphanage, before being evacuated to England. The Nazis kidnapped over 200,000 Polish children in attempts to destroy their culture and Germanise them. It sounds like distant history, but to this day, we do not say the word “Hitler” around Babcia.

Babcia looks the most like me and I’m unashamedly her favourite. She keeps her important contact information scrawled in the back of a photo frame, a pic of me as a kid, the one item she’ll grab if she’s ever forced to evacuate again.

I worry, next time I see her, if she’ll notice my kidnapped nose and be sad.

I’m not claiming my grandparents’ trauma as my own. Anybody should be angry about having their body altered without sober consent. I hope this added context explains just why I’m so furious.

When Dziadzu and Babcia met in England, they fell in love, and passed down their genes to a gaggle of lovely daughters, and then the nose found its way to me. Its existence is proof that generations of my face have been adored. I never found our nose undesirable; my surgeon decided that it was. In a split second, he destroyed everything my family went through to preserve it.

Babcia, Dziadzu, and everyone before you – I’m sorry.

(Unrelated side note: this is why oral history is so important. Nazis destroyed entire genealogies. My heart aches in awe and envy when I hear a whakapapa recited, a history which lives on despite attempts to quash it.)

A darling friend of mine, who is eerily identical to me but Actually Jewish, had a similar septoplasty experience. Her surgeon asked if she wanted her nose flattened. My friend said no, and thankfully got away with her hump intact. I wonder if these surgeons genuinely believe that they are being helpful. I wonder how many people enter their offices, excited at the prospect of breathing, only to leave feeling ugly. I wonder their motivations – a laudation to Western beauty standards? An extra paycheck? Just for funsies?

My English name is Ashlie. I have never been called it, ever. It’s my dark secret, like Ashley Spinelli from Recess. Since I was born, I have been called Asia, a Slavic diminutive used by loved ones. These days I look into the mirror and see a little more Ashlie than Asia. But I do know that my big wonky nose is still nestled within the matryoshka of my genes, a carefully wrapped gift from my grandparents and their grandparents before them.

It ties me to centuries of history and family who’d survived in spite of persecution due to this very schnoz. I think about how it crafted my face into someone unique, and the upset of looking into the mirror at a reflection I don’t recognise. It feels like a betrayal to both my progenitors and inner worth. My history is no longer on my face, but it’s inside of me, and I shrug into my soul like an old comfy bathrobe.

There’s been a mixed reaction to my nose. Some can’t see a difference. Some pick up on it immediately. The septoplasty worked well for a few months, but it’s begun caving in again. I lost my nose for nothing. I don’t trust any surgeon to get it refixed anymore.

This is a dirge to conventional beauty standards, to wretchedly unethical medicine, to forgoing consent. Mostly, though, it’s a love letter to fat wonky schnozzes, to their charm, and the stories they carry. A big nose can mean the most beautiful gift in the world. I just wish it didn’t take mine being stolen to realise it.

*This is a joke. TikTok is awful.