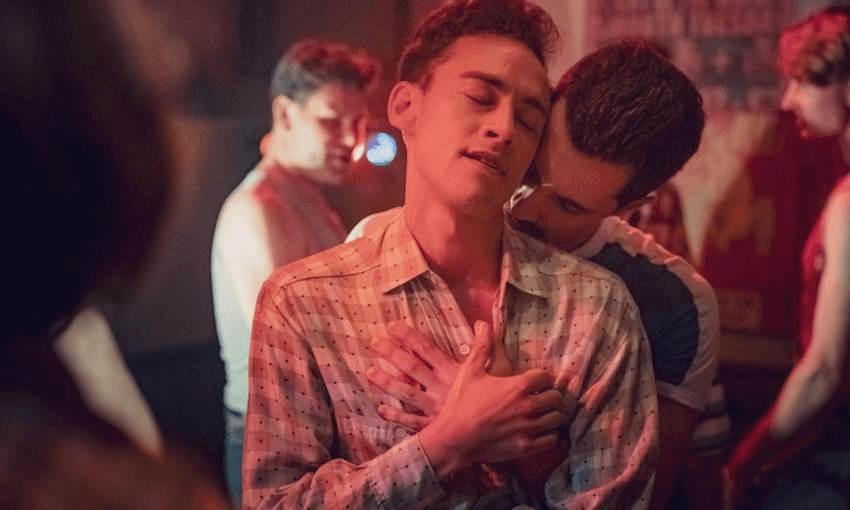

Sam Brooks reviews Russell T Davies’ It’s a Sin, which tackles the Aids crisis in a powerful, intimate way.

Early on in It’s a Sin, Russell T Davies’ new drama about the HIV/Aids crisis in 1980s London, the disease is still so new that Ritchie – the show’s protagonist – refuses to believe it even exists: “How do I know? How do I know it’s not true? Because I’m not stupid.” They’re words that hit differently in 2021. After a year of studiously ignoring Covid denialists, hearing someone in the midst of a plague proudly denounce it as fiction makes your stomach turn – even more so when you know that plague will go on to kill more than 32 million people.

It’s a Sin is full of moments like these. Where The Normal Heart raised a clenched fist to the Aids pandemic, and Angels in America used the plague to critique national identity, It’s a Sin goes small and intimate. While those earlier dramas were first and foremost artistic responses to the crisis, It’s a Sin puts the audience right in the middle of it, creating a hyper focused and specific portrait of 80s London in the midst of the worst pandemic in living memory. Davies plumbs his own life as a gay man to pay tribute to the lives lost, and the culture that was hugely changed by Aids, in a way that feels so authentic at times it might as well be documentary.

Across five episodes, It’s a Sin follows five friends as they first encounter Aids, and then experience its brutal reality. Ritchie (Olly Alexander from the band Years & Years) has a familiar, tragic arc, fucking his way through the decade while hoping the worst doesn’t happen to him. Roscoe (Omari Douglas) rebels loudly and defiantly against his Nigerian father, while Colin (Callum Scott Howells) creeps out of the closet, and Ash (Nathaniel Curtis) skates along quietly and happily. Tying them all together is Jill (Lydia West) who pivots, as many lady friends of gay men did at the time, into advocating and caring for those with the disease.

From the opening scene, the series places the viewer in a very specific time and place: a London feeling the full force of Margaret Thatcher’s ruthless politics. Davies achieves this not just with music (you better believe that the show has a ‘Smalltown Boy’ needle drop and doesn’t make you wait for it) but with the contrast between the saturated colours of the nightlife scenes and the drab brown and grey of everyday life. Across the series, Davies’ eye for a London that he clearly knows well pays dividends. It’s everything to these men – heaven, hell, purgatory.

As a writer, Davies needed to strike a balance between the stories of queer people, largely men, with those of their allies, who played a vital role in the response to the Aids pandemic. While Ritchie is the series’ focal point, our main window into the story comes via Jill, based on Davies’ real life friend. When the boys are still sceptical about its seriousness, she’s the one who does all the research on this new, mysterious disease, who later advocates for her friends at hospitals, and who eventually devotes her entire life to taking care of those with Aids. Centering Jill in this way is a clever storytelling technique and, speaking as a queer man, one that works beautifully. We’re in 2021 – we know there were few happy endings for the gay men who experienced the worst of the 80s Aids crisis. Seeing parts of this story through the eyes of an ally allows us to gently to look in, rather than live within the same hell that they did.

There’s no denying the uncomfortable pang of recognition that comes from watching a series about a pandemic when you’re living through one yourself. Characters not knowing what the pandemic is, how bad it is and when it’s going to end – it all gives It’s a Sin extra emotional heft. In one episode set in the pandemic’s early stages, Jill meticulously cleans her flatmate’s beloved teacup after a man with HIV drinks from it and ends up smashing it because she’s not sure how clean is clean enough. It plays out like a scene from a horror movie. You can’t help be reminded that it wasn’t so long ago that we were all meticulously washing our groceries, and that, for the rest of the world, that sort of fear is still very much a reality.

Chillingly, these parallels only highlight the enormous gulf between the public response to the ‘80s HIV/Aids pandemic and that of the Covid-19 pandemic today. When one character claims if “heterosexual boys were dying in these numbers” they’d have cured Aids already, it rings true. Treating gay men as a disposable minority is nothing new, but to be reminded of it now – when vaccines are going into arms barely a year after Covid-19 was first identified – leaves a bitter taste. If it feels uncomfortable, that’s because it should. The pedestrian response to the Aids crisis was, and is, a tragedy, and one of the most abhorrent cases of governmental and societal neglect in living memory.

What makes It’s a Sin brilliant is that it’s not just a heartfelt tribute to the gay community of the 1980s, but an impassioned call to look back, and to learn. The Aids pandemic didn’t have to be so devastating, and neither did the global Covid pandemic. Davies never leans away from the politics of Aids: it was a “gay disease”, and it was treated like one. When Jill tells Ritchie’s mother that his disease is her fault, Davies is saying that the proliferation of Aids was enabled and encouraged by a society that refused to look it in the eye. The shame was as much a poison as the virus itself. But the thing that lingers long after the credits roll? It’s a Sin is not about men who died, but about men who lived. When Ritchie, in the later stages of the disease, smiles and says, “I had so much fun”, you feel it. Davies celebrates the fun that Ritchie, and millions of men like him, had while also paying tribute to their loss, and society’s loss. Pandemics are political, but they’re also personal. It’s a Sin reminds us that every loss is a tragedy, one that shouldn’t be forgotten.

You can watch It’s a Sin on TVNZ on Demand right here.