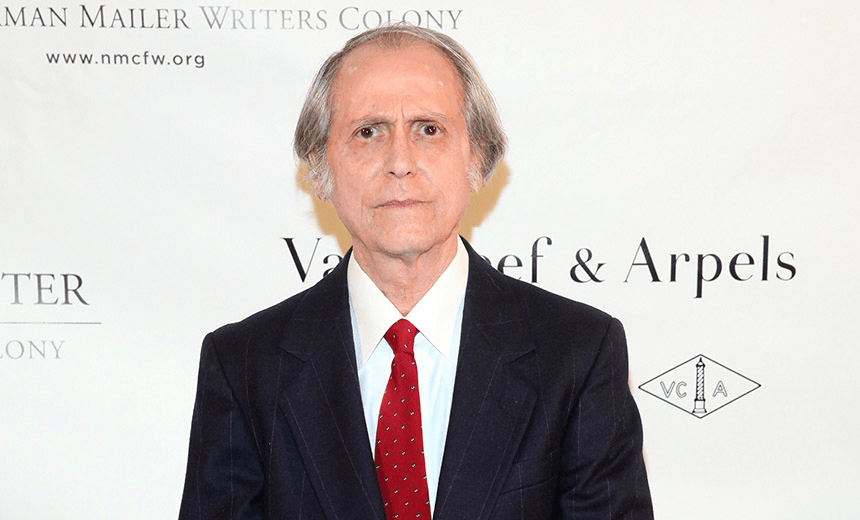

The world is a fucked-up place with terrorists controlling the narrative (and the images), and distracted, anxious, over-fed America slouching towards a Trump apocalypse. Don DeLillo anticipated the way things have turned out; to mark the publication of his latest book, the Spinoff Review of Books devotes the entire week to the work of maybe the world’s greatest living novelist. Tom Moody begins the series with an introduction and overview of the master.

Don DeLillo elicits extreme reactions in readers. His work — and thoughts about his work — have been variously described as “beautiful and profound”, “dazzling and prescient”, “tired and brittle”, and “beneath comment”. Libra, wrote George Will, wasn’t just a bad novel: it was “an act of literary vandalism and bad citizenship.” Few literary authors have to deal with this kind of accusation.

From his debut novel Americana in 1971 to his latest book Zero K, he’s spent five decades excavating an A to Z of American obsessions — the ambiguity and randomness of life, catastrophes, conspiracies, death, mass delusion, technology, America itself.

He’s won the National Book Award (for White Noise) and the PEN/Faulkner Award (for Mao II), and the New York Review of Books declared he was “the chief shaman of the paranoid school of American fiction”.

DeLillo is the son of Italian immigrants, born and bred in the Bronx; he didn’t read at all as a child, he once told the Paris Review. “This is probably why I don’t have a storytelling drive, a drive to follow a certain kind of narrative rhythm.”

Describing his plots – where little seems to occur – reveals little about his novels. Many defy plot summary. It’s tempting to say that not a lot happens, but something complex and intriguing is always there, bubbling under the surface.

His characters may work in banking or archaeology; they may be ghostwriters or rock stars, risk analysts or mathematicians. His novels may address the Cold War or the new global terrorism, suitable material for a novelist who often explores the notions of paranoia and power. Language, too, is an ongoing theme.

As a teenager, he read Faulkner and Joyce while he should have been working as a playground attendant. It was through Joyce, he’s said, that he “learned to see something in language that carried a radiance, something that made me feel the beauty and fervor of words, the sense that a word has a life and a history. And I’d look at a sentence in Ulysses or in Moby-Dick or in Hemingway . . . All this in a playground in the Bronx.”

These insights into his start — as a reader and writer — have emerged slowly over the years. Early in his career, DeLillo rarely granted interviews, unusual for a young writer trying to make a name and build an audience: he provided few clues to his work, and even fewer details of his life. Reference books listed only his date of birth and publication dates.

He told critic Tom LeClair: “It’s my nature to keep quiet about most things. Even the ideas in my work. When you try to unravel something you’ve written, you belittle it in a way. It was created as a mystery, in part . . . If you’re able to be straightforward and penetrating about this invention of yours, it’s almost as though you’re saying it wasn’t altogether necessary. The sources weren’t deep enough.”

In an interview with Kevin Rabalais in the New Orleans Review, DeLillo said, “I think the novel is a mystery. To me, it’s all a mystery: where an idea comes from, how characters develop, how sentences develop, how a conclusion is determined, how a writer finds his way to the end of the book. All of this seems mysterious to me.”

Mysterious or precious? Complex or opaque? His fiction demands a lot from his readers. The novel, he believes, needs “a more serious kind of reader”, because he believes that “the most successful work is so demanding,” as he told The New York Times in 1982. “The novel’s vitality requires risks not only by [writers] but by readers as well.”

Even academics have weighed in on the difficulty of DeLillo’s writing. Frank Lentricchia, editor of (the surprisingly accessible) Introducing Don DeLillo, declares that the “books are hard: all of them expressions of someone who has ideas (I don’t mean opinions), who reads things other than novels and newspapers (though he clearly reads those too, and to advantage), and who experiments with literary convention.”

When DeLillo was asked, by the Paris Review, if he’d hoped to find a larger audience by publishing Libra — his only bestseller, about Kennedy’s assassin Lee Harvey Oswald — he demurred. “I wouldn’t know how to do that,” he said. “My mind works one way, toward making a simple moment complex, and this is not the way to gain a larger audience. I think I have the audience my work ought to have. It’s not easy work.”

DeLillo is sometimes called a writer’s writer, which usually means someone who has an out-sized critical reputation but not that many readers. Certainly, when he talks about his writing process, it feels as though he’s addressing a room full of other writers. “The basic work is built around the sentence,” he said in The Paris Review interview. “This is what I mean when I call myself a writer. I construct sentences.”

This construction work is done on a second-hand manual typewriter, a habit that will have some readers and critics rolling their eyes. Not just a typewriter but a manual typewriter; not just a manual typewriter but a second-hand one.

His emphasis on the primacy of the sentence over the story appeals to other writers — fans include Jonathan Franzen and Lorrie Moore. Joshua Ferris, in his review of DeLillo’s latest novel Zero K in The New York Times, wrote: “I don’t read a DeLillo novel for its plot, character, setting . . . I read a DeLillo novel for its sentences. And sentence by sentence, DeLillo magically slips the knot of criticism . . . Sentence by sentence, DeLillo seduces.”

Reviews often praise the “beautiful sentences”, suggesting DeLillo belongs more in the company of Michael Cunningham, say, than his contemporary Philip Roth. Martin Amis has argued that “Underworld may or may not be a great novel, but there is no doubt that it renders DeLillo a great novelist.”

But can someone be a great novelist without writing at least one great novel?

*

Throughout his novels, DeLillo has plumbed numerous themes with an obsessive focus. Shadowy conspiracies. Catastrophes. Glossolalia. Terrorism. A lone man in a room features in Great Jones Street, The Names, Libra, Mao II, and Point Omega.

DeLillo often expresses the simultaneous embrace and fear of contemporary life. Here, from White Noise, is his riff on the majesty of the supermarket:

In the mass and variety of our purchases, in the sheer plenitude those crowded bags suggested, the weight and size and number, the familiar package designs and vivid lettering, the giant sizes, the family bargain packs with Day-Glo sale stickers, in the sense of replenishment we felt, the sense of well-being, the security and contentment these products brought to some snug home in our souls — it seemed we had achieved a fullness of being that is not know to people who need less, expect less, who plan their lives around lonely walks in the evening.

And here is that novel’s protagonist, Jack Gladney: “Why do these possessions cast such sorrowful weight? There is a darkness attached to them, a foreboding. They make me wary not of personal failure and defeat but of something more general, something large in scope and content.”

In the world of DeLillo’s work, technology inspires both awe and fear. “Technology makes reality come true,” exclaims a character in Underworld. But a character in Zero K asks, “Haven’t you felt it? The loss of autonomy. The sense of being virtualized. The devices you use, the ones you carry everywhere, room to room, minute to minute, inescapably. Do you ever feel unfleshed? All the coded impulses you depend on to guide you. All the sensors in the room that are watching you, listening to you, tracking your habits, measuring your capabilities. All the linked data designed to incorporate you into the megadata. Is that something that makes you uneasy? Do you think about the technovirus, all systems down, global implosion? Or is it more personal? Do you feel steeped in some horrific digital panic that’s everywhere and nowhere?”

In the book UnderWords: Perspectives on Don DeLillo’s Underworld, the opening essay begins with these words:

There is surely something defiant about a constellation — not the secondhand act of locating one in the night sky, but rather the original work of fetching a convincing pattern from such forbidding vastness. It is a telling exercise — horrified over the irrevocable implication of our puniness, the ancients indulged a fondness for invented (hence, manageable) complication, the familiar love of control implicit in devising any system, the deep intoxication of controlled intricacy.

Perhaps we should think of DeLillo as one of those ancient astronomers — sharper-eyed and more clever than most of us — finding unseen patterns and mapping a universe for all of us to see.

The Spinoff Review of Books is brought to you by Unity Books.