Settlers, farmers and scientists have all had their way with the once lush piece of land adjoining Taitā College. Nadine Hura meets the students and teachers reclaiming the forest and wetlands.

I think you can fall in love with a place once you know its story. Or you can at least start to see it differently. Every Thursday for the past year I’ve driven from Porirua to Taitā, around the glassy Pauatahanui inlet, through the undulating Haywards, and across the meandering Awakairangi.

It’s a long way to go for anything, let alone an art class. But there’s something about the shadowy forest behind the Learning Connexion that keeps me re-enrolling term after term. The long driveway feels like a throat that could almost swallow you whole. The tūī really sing their hearts out in Taitā.

In a former life, the art centre was home to the Department of Scientific and Industrial Research (DSIR), and before that it belonged to the Soil Bureau. The room where I’ve been learning the difference between intaglio versus relief printmaking was very likely used by scientists in the 70s and 80s to conduct tests and record chemical reactions. The table next to the window where I sit and carve amateur pictures into lino has been repurposed from a laboratory bench that I like to imagine once held samples of dirt and beakers of fluid.

Before the artists moved in and painted the brutal concrete exterior in a mural straight from the pages of Dr Zeuss, scientists made discoveries here that would one day change the entire landscape of Aotearoa. Literally. I sometimes look out at enormous kōwhai in bloom and think of those groundbreaking studies that assisted farmers to treat illnesses in cows, which paved the way for large tracts of land to be turned from native forest into pasture.

All along this rugged knuckle of land where tūī hurtle through the branches like spitfire pilots, scientists planted and studied exotic trees, and those trials would eventually contribute to the knowledge and expertise that makes this nation today so adept, so dependent, so deeply invested in pine.

Blackberries really aren’t so sweet

Next door, on the same piece of land, Taitā College has witnessed it all. Cohorts of students have come and gone, some have even returned as teachers, but the pines and acacia wattles beyond the classroom windows have dug in and clung on.

To an average visitor the forest looks healthy. Lush, even. But there are limits to what the eye can see, let alone measure.

Matua Haimana Hirini, kaiako at Taitā College, lives on site in the caretaker’s house. He was a student here in the 80s and returned in 2010 qualified to teach Māori, English and Science. He says he looks out the window and sees problems, and he’s not talking about the students. He’s talking about the blackberry. The gorse. The wilding pine and cherry blossoms. He’s talking about the possums and the deer. He’s talking about what’s been lost. Things I can’t see: a disappearing wetland. Buried cans and bottles and rotting fence posts. Eels and frogs in the night. Mānuka in a fight for their life. Harakeke that just wants a chance.

Matua Hirini explains that Taitā refers to the bend in the river where the driftwood collects. “You have to know the story of the place for that to make sense.”

He holds up his finger, as if reading my mind. “The reason you’d want to know where the driftwood collects is if you were building pā tuna.”

The chapter in Taitā’s history when Te Awakairangi was teeming with life and the braided river still detoured through Taitā is the one Matua Hirini is trying to restore. Two and a half years ago he stopped teaching Te Reo Māori in the classroom and transferred all the learning to the wetland between the school and the Learning Connexion. Ahi Kaa is less about language in the textbook sense, and everything to do with reclamation — land and language. Language via land. “You learn Māori through a Māori way of living and seeing and doing. If kids know what used to be here before then they can imagine what it can be again.”

The story of the soil beneath Taitā College begins long before the artists and scientists took up residence, before the farmers with their fence posts and the market gardeners before them, and certainly before the settlers who carefully wrapped the roots of their favoured blackberry and transported them to the colony so they might always have a taste of home in their jams and pies.

“Ahi Kaa isn’t a class,” Matua Hirini says. “It’s direct climate action. Students are working to change the environment, but the environment is also changing them. They’re working to liberate the natives from the pine and the pests, and at the same time, they are also being liberated. I can see it. As we reclaim the wetland we are making our site more resilient, and the students are becoming more resilient. Any kid who can spend all day in the swamp in the rain and then come back and do it again next week has got some level of self-reliance and resilience.”

This is one reason Matua Hirini doesn’t use the word ‘kaitiaki’ in reference to humans. “You’re not the reason, you’re just the conduit. The land teaches you this. You can feel it when you’re out there.”

Maraea, a year 10 student, says that what she loves the most about being in the swamp is the visits from the pīwaiwaka. “At the beginning of the year we didn’t see them very often, but since we began clearing the blackberries we see them all the time.”

Matua Hirini says some kids used to be scared of the pīwaiwaka because of the stories they’d heard. “But I remind them, they’re our kaitiaki. The pīwaiwaka come and check us out in the swamp. They flit and dart around us when we’re working. They’re curious, they want to know what we’re up to. They’re just like these kids. They have the same qualities.”

‘Kids are being made to feel as if they’re stupid’

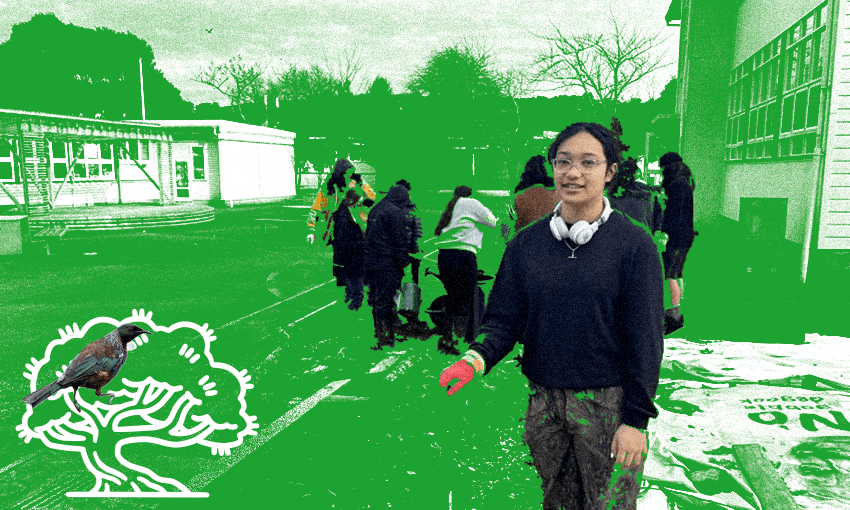

Jacinta Po Ching, a year 13 Ahi Kaa student and Head Girl of Taitā College takes me on a tour of the swamp. She points out where the blackberries used to be, and tells me how they had to replace their gumboots regularly because they kept ripping open on the backward facing thorns. They brought down cherry blossoms and ring barked pines, set live traps for the possums and opened up the creek which was choking on weeds, clay and concrete.

Once cleared, they began harvesting harakeke from other areas, and planting cuttings where the blackberry had once crept across the mud. The drying blackberry branches are then piled high nearby and used as fuel for the hāngi pit whenever there’s a hākari at the school.

The philosophy of zero waste is ingrained in the Ahi Kaa students. Matua Hirini explains that even that word “waste” in Māori doesn’t really make sense, not in the way that it is understood in English. “The word ‘moumou’ refers to the wasted potential of something. The word ‘para’ refers to rubbish, but that’s really just describing the nature of something, for example, something dirty. But the idea of waste in Māori is quite foreign. We don’t waste things, everything has purpose and value.”

Lani Rotzler-Purewa, a kaimahi with Parakore, started working with the Ahi Kaa students this year. When it comes to waste, she says she is more about the carrot than the stick. She and friend Tina Walker-Fergusson have helped establish a māra at the back of the school, teaching the students how to compost — or make soil, as she calls it.

“It’s hard to align the knowledge of our whakapapa to our actions, Lani says. “I can see the pressure people are under. There can be a lot of shame associated with it too. People are ashamed of what they don’t know. Food scraps releasing methane into landfill is science heavy kōrero. It’s hard to make that meaningful to anyone. Even I was surprised to hear that putting food scraps into landfill is damaging, cos you’d think it just rots down and becomes part of the good stuff. But that’s not the case at all. You need aerobic bacteria to break down the kai. We bury our food scraps, layering the green and brown, and then the ngoke come. From a scientific perspective, it’s a crazy orchestra of different players that make magic happen. As a kaimahi māra, we are just one player in that beautiful orchestra.”

Lani says that scientists sometimes think they are superior because of the language they speak. But we have the knowledge too, Lani says. “We just have it in a more palatable form. In scientific language we talk about the microbiome and soil health affecting the health and nutrients of the food we eat. Another way of thinking about it is through the relationship between Hineahuone (the first woman created) and Tāne. Tāne is personified in all tipu, in all rākau, in every single plant that is green. Tāne breathes life into Hineahuone. If Hineahuone is well, the food we eat will be well.”

Lani says that even though she’s not an expert in mātauranga, it feels natural, as if she is remembering and unlocking knowledge of our atua that she already has inside her. This is despite being told by her high school science teacher — not Taitā College — that she should go and flip burgers at McDonalds.

I ask her how she feels about that comment today, and her eyes become glassy, like she hasn’t yet fully shed the weight of it.

“I think it’s still happening in classrooms you know? Kids being made to feel as if they’re stupid. That’s why I love working here at Taitā College. I hope the students are learning and feeling confident in what they know.”

School not just about grasping for credits

Matua Hirini knows that assessments and targets can sometimes be counter productive. “If we were chasing credits we wouldn’t be able to do half the things they’re doing in the class. Credits take up so many hours that we’d end up spending more time in the classroom than we would doing the work. But we’re not doing this for credits, we’re doing this for the environment.”

More to the point, what we measure tells us what we value. Matua Hirini says he wants students to know that assessments are not a reflection of what type of person you are. “I see myself in some of them, I see my friends. I went to school with some of these guys’ parents. Hard cases some of them. Some people might think they’re naughty. No they’re not. They’re alive, their lights are on. They’re smart. Cheeky. Just like the pīwaiwaka.”

If Ahi Kaa isn’t about credits, and the work is hard, painful and slow, what’s the reward? I ask Jacinta why she’s so invested in it.

Jacinta sticks her shovel in the ground and thinks for a moment. We’re standing in the looming shadow of an enormous pine that was planted long before she was born.

“It’s not always simple to explain. I think back to how I started, it was really just around knowing what I have lost. What my whānau has lost. I learnt in history class that some of the settlers brought plants here that they liked, so that they could feel more at home. I learned about the ways the land has been misused. My nanny wasn’t allowed to kōrero Māori when she was at school, so we lost the language. When I hear my cousins speaking Māori I see what I missed out on. I want to get it back, not just for me but for my mum too.”

Tāne Māhuta cares about more than carbon

Data isn’t neutral, and scientists leave more than just furniture behind when their attention diverts. Today, much of the reason pine forests have a head start in the battle to save the climate through carbon farming is due to the sheer volume of research that exists about how and where to grow them. The Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS), which is one the key tools the government relies on to help reduce carbon emissions, has multiple formulas (or Look Up Tables) to assess the level of carbon sequestration by exotic trees. By comparison, only one Look Up Table exists for natives.

Far less is known about the conditions that support Tōtara and Kauri and Mānuka to thrive, because they weren’t vigorously studied. Even if scientists had wanted to study the delicate ecosystems of ancient forests and their potential to sequester carbon, they couldn’t, because they were felled and logged into near-extinction at the turn of last century.

It’s almost a foregone conclusion in the current context that pine will be the preferred tree for carbon farming, not just because that’s where the bulk of the investment and expertise has been, but because the urgency of the Government’s need to meet reduction targets by 2050 mean that exotic trees are more attractive to investors: they grow faster therefore make money faster. Too bad for natives which, at least by colonial notions of time, grow far too slowly to compete with non-indigenous species.

The responsibility for the situation lies not with scientists, nor with landowners responding to various financial incentives logically, but with the mechanisms and tools of a settler colonial government which continues to hold fast to the values, activities and beliefs that caused global warming in the first place.

It seems like the kauri in the forest to say it, but weighing, pricing and profiting from carbon reduction seems to perversely value one thing to the exclusion of all others: carbon. It narrowly distorts the purpose of Tāne Māhuta as being only about sequestering carbon. Never mind Tane’s role supporting and sustaining the well-being of all other living species – from the pīwaiwaka to the student to the harakeke. But, unlike tonnes of carbon, there is no formula to quantify, trade or profit from things that, by definition, want to be equal.

Layers of thick white paint

Irony makes for the best and worst stories. Inside the foyer of the Learning Connexion, painted directly onto the concrete wall, is a mural of a Māori chief. He is surrounded by people, using his bare foot to drive a large digging stick into a soil brimming with kūmara. The artist, E. Mervyn Taylor, said he chose the scene to express the value of the relationship between Māori and Pākehā, and the partnership that was once envisaged between western science and traditional Māori knowledge. He titled the mural “Kia kitea te waewae tangata — loosely translated “‘behold, the toil that yields sustenance.”

Inexplicably, but perhaps predictably, the mural — and the vision — was at some point painted over. A note at the entrance, under a replica photo, says the original artwork and its aspirational vision of partnership is now “irretrievable” under layers and layers of thick white paint.

Matua Hirini, who also happens to go barefoot, has other ideas. I ask what keeps him motivated and he speaks slowly, which I can either construe as gravity for the profound nature of what he’s about to say, or evidence that the answer is obvious. It turns out to be both.

“I am tangata whenua. I am not Māori, I am tangata whenua. What makes me tangata whenua? The whenua. If I have no relationship to the whenua, then I’m just tangata. That doesn’t make any sense. We are nothing without the land.”

This is the kind of incentive and reward that traditional western systems of measurement aren’t set up to see, let alone value.

These motivations, both seen and hidden, positive and negative, yield outcomes that stubbornly defy standardised measurements.

Like teachers who have looked at Māori students year on year and told them they were destined no further than a McDonald’s grill.

Like the impact Jacinta has had on her Mum, who has taken up te reo lessons, and her Dad, who is learning how to compost from his daughter, who learnt from her mentors.

Like the art centre that was once an institute of soil research, that was once a market garden, that was once a farm with wild blackberry, that was once, and always will be, the bend in the river where the driftwood collects.

This is Public Interest Journalism funded through NZ On Air.