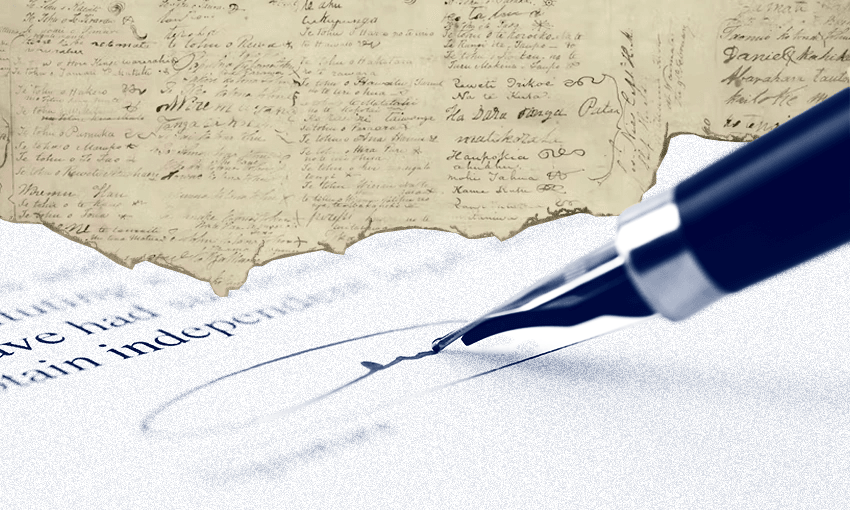

When the Crown is the self-appointed ultimate authority over a process to deal with Crown misconduct, we run into big issues, writes Tina Ngata.

“What’s it going to take for Ngā Puhi to settle” was the headliner statement on Q&A last weekend, as Ngā Puhi chair Mana Tahere was interviewed about the country’s largest iwi’s ongoing negotiations with the Crown. Negotiations between the two started in 2009, and in 2014, the Tūhoronuku Mandate board was established to represent the iwi. After 15 years, the process is ongoing, with Tahere predicting there’d be a settlement within the next five years.

The question itself, however, unfairly pointed the finger at Ngā Puhi for the delay. Māori are not the problem in “settlement” culture. Crown arrogance, interference and over-reach is. Sadly, misunderstandings about the “settlement” process are all too common in Aotearoa. The common colonial view is that settlements are a cash-grab, a part of the “special privileges” Māori apparently get. Rarely is there an appreciation for the demoralising, harmful and ultimately unjust process that settlement entails.

The Crown government has repeatedly positioned the tribunal and settlement process as a means of “settling the grievances of its Indigenous people”. This very positioning points to the problem, that the Crown assumes itself as the paternal authority and Māori as aggrieved subjects, rather than treaty partners. The Crown’s continued practice of painting redress as a tacit acknowledgement of Crown sovereignty, has necessitated a number of iwi to explicitly address this in their settlement text.

The settlement process normally plays out through direct negotiations with what was once the Office of Treaty Settlements and is now Te Arawhiti (Office of Crown-Māori Relations), who reports to the minister for Treaty of Waitangi Negotiations, currently Paul Goldsmith. If there are issues that cannot be resolved (like the matter of mandate), the Waitangi Tribunal may also be involved. The tribunal is appointed by the Crown (specifically, by the governor-general, on the recommendation of the minister of Māori affairs, in consultation with the minister for justice).

The Waitangi Tribunal was established in 1975 to hear claims on Crown breaches of the Treaty, with historical claims being heard since 1985, and direct settlement negotiations being favoured since the 1990s. By this point, the Crown policy and legislation had been enforcing poverty upon Māori for over 150 years, some seven generations. Of course, over successive generations, the harm grows new forms, like a liana vine. Housing poverty turns into intergenerational ill health, which in turn affects education and employment. Crown abuse turns into institutional resentment, which in combination with desperation leads to crime. The victim-to-perpetrator cycle revolves numerous times, and with each generation, the consequences of the initial harm become increasingly complex. All the while, contemporary Treaty violations continue to be layered over us, creating new liana vines. None of this excuses personal responsibility, but it should be kept in mind when people are asked to quantify the cost of multiple generations of economic, socio-cultural and political dispossession.

When the Crown is the self-appointed ultimate authority over a process to deal with Crown misconduct, we run into big issues. For example let’s look at the Large Natural Grouping Policy: Te Tiriti o Waitangi was signed with hapū, not iwi. However, the Crown found it inconvenient to negotiate at the hapū level, figured it would cost too much, and take too long, and so decided it will only enter into negotiations with those who meet the Crown criteria for a “large natural grouping” – effectively erasing its treaty partner and replacing it with a more convenient grouping.

These Crown-defined processes of who counts and who doesn’t, played out over decades, has come to shape Māori identities and relationships in profound ways. You can imagine the tensions this creates between kin-groups both as hapū and iwi, as well as those classed as hapū, who see themselves as iwi, and between neighbouring iwi who may have overlapping interests. The settlement process is an atom bomb upon kinship relations. It creates rifts between whānau, hapū and iwi that can take generations to recover from. As they say, first the earthquake, then the disaster. In this case it’s first the colonialism earthquake, then the settlement disaster.

The obsessive focus on money diverts the discussion away from the factor of power. Power to make ultimate decisions for your people, lands and waters. Even settlements that include the return or co-management of taonga, the Crown still holds the power to de-legislate, re-define, or to restrict funding that gives effect to the aspirations of the people for that taonga. We are seeing this play out right now, in the Fast-Track Approvals Bill, which reviews the level of protection for taonga designated as waahi tapu (sacred sites) or areas with recognised “special interest” for iwi in prior settlements.

It’s a quagmire of harm, with the Waitangi Tribunal being the primary site of recourse – and of course that, too, is limited (by the Crown) in scope and enforceability. Although the tribunal is a judicial arm of government, it is not a court of law, and the recommendations are not binding. While the government has honoured many recommendations, it has also ignored many – the Flora, Fauna, Cultural and Intellectual Property, Foreshore and Seabed, and the Paparahi o te Raki findings and recommendations being prime examples.

Reflect on that for a moment: The Crown assumes its right to govern from the Treaty. The Treaty apparently matters enough to form a government on, but not enough to make the treaty enforceable in any other way.

So rather than asking “what will it take” for any iwi to settle – perhaps we should instead be asking what it will take for the Crown to stop creating shitty processes, every single day, that compound their enduring history of shitty processes. Perhaps we should be asking of ourselves, why we are still allowing processes that not only ignore tikanga Māori, but also fail the most basic standards of Western international treaty and contractual law, and what will it take for us to demand better from our government?

The answer was offered multiple times by Moana Jackson: Treaties aren’t meant to be settled – they’re meant to be honoured. The most important way in which Te Tiriti o Waitangi remains to be honoured, is through a formal constitution that recognises Māori political authority over Māori destinies. Until then, the only appropriate thing we should be directing to groups undergoing “settlement” processes is aroha, time, grace and sympathy.