Bea Joblin (Ngāti Pākehā ki Airangi me Kōtirana), a registered translator and a teacher of te reo Māori to children and adults, examines the importance of making te reo a daily staple for future generations.

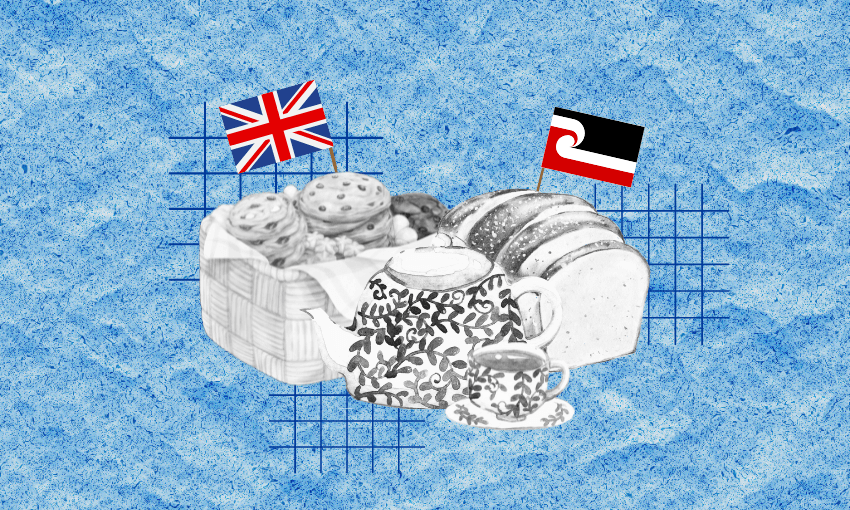

Food is a rich source of figurative language in most cultures (“biting off more than you can chew”; thinking someone is a “snack”; “chewing the fat”; “living a champagne lifestyle on a beer budget”) and te reo Māori is of course no different. With Te Wiki o Te Reo Māori upon us, I’ve been thinking about a few kīwaha that speak to how we, as tauiwi, sometimes engage with this kaupapa. It can seem like we eagerly tuck in to te reo Māori during this one week alone, like an annual Christmas pavlova, a sometimes food.

A question we might ask ourselves as tāngata Tiriti who care about supporting our Māori whānau in the revitalisation of their language is this: is speaking te reo Māori a mahi kai parāoa for us, or is it just a timotimo? And while we may be content to subsist on our reo pihikete, what about all those tamariki mokopuna Māori whose growing hearts and minds need daily nourishment from te kai a te rangatira?

Ahakoa te mea kei te tino pīkoko te tangata ki tēnei kai mā te hinengaro i tēnei wiki tonu, he uaua pea te hoki anō ki tēnei kai rā roto i te tau katoa. Although every September people are hungry for the brain nourishment that comes from learning te reo Māori, it’s undoubtedly harder to keep up a commitment to a second language throughout the year. In this sense, te reo Māori almost becomes a timotimo – a quick snack, but not the bread and butter of our everyday verbal interactions as a community.

However, learning Māori isn’t a fleeting lockdown hobby. It shouldn’t be treated like that macaron-making obsession you regret buying a stand mixer and multiple piping bags for. For Māori, whether this language is full of life or wasting away is more than an intellectual curiosity – it’s a matter of cultural and spiritual wellbeing.

By the early 20th century, when Māori language trends were beginning to shift massively – from 95% fluency in 1900 to an estimated 15% in 1975 – English was already being referred to as a “reo pihikete”. This was a reference to it being the language needed to buy biscuits from Pākehā shopkeepers, or to engage in necessary activities outside of Māori communities.

The term “reo pihikete” has also been used over the years as a gentle whakaiti, describing formal English as dry, functional, and lacking richness or nourishment. Even some Pākehā scholars agree with this view of modern English in the civil and commercial context, noting how industrialisation has drained away the lyrical fluidity of earlier forms of the language. Modern English has become a language of commerce, with capitalist communication demanding a utilitarian, standardised clarity above all else.

While “reo pihikete” may offend some, it’s important to note how, for indigenous people, it might be difficult to derive spiritual, creative and intellectual nourishment from a language that was used to oppress your ancestors, supplant your own tongue and rewrite your stories – a language that continues to be wielded by racially biased institutions today.

On the other hand, te reo Māori is often referred to as “te reo rangatira”, a term that potentially has connections to the whakataukī “He aha te kai a te rangatira? He kōrero, he kōrero, he kōrero”, or “What is the food of chiefs? It is language, it is language, it is language.” This potentially speaks to the deep, spiritual fullness many Māori report feeling when they reconnect with their reo.

Another phrase that comes to mind is “kai parāoa”, which literally means “eat bread” but also figuratively means “everyday”. In 2020, Rawinia Higgins (Ngāi Tūhoe), deputy vice-chancellor of Te Herenga Waka and chair of Te Taura Whiri i Te Reo Māori, outlined in an RNZ interview the five key elements of language revitalisation, one of which was use.

Vincent Olsen-Reeder (Tauranga Moana, Te Arawa) explores this element of use in his doctoral thesis, Kia Tomokia Te Kākahu o Te Reo Māori. He highlights one of the greatest challenges facing te reo Māori today, getting people to choose to use the Māori they know, thereby restoring te reo Māori to its status as mahi kai parāoa, or an everyday activity. In his exploration of this issue of use, Olsen-Reeder also describes a psychological shift from identifying as a learner of te reo to a speaker. This is what will help move te reo Māori from our classrooms into our homes, cafes, Ubers, libraries, nightclubs, indoor rock-climbing gyms, dermatologists’ offices, high-end health food stores, and other essential spaces.

How can speaking Māori become mahi kai parāoa – something we use to flirt with that “snack”, or tell our kids they’ve only got five more minutes on the iPad for the sixth time in half an hour – if we only do it once a year?

Even if your own wellbeing doesn’t hinge on te reo being a living, breathing language out in the world, how does its everyday presence affect young Māori? They’re developing their identities in a post-colonial context, and seeing te reo Māori used regularly could significantly shape how they perceive themselves and the world.

Data shows that indigenous children schooled in culturally responsive environments – ie in Māori-medium settings, surrounded by their language and culture – do far better than their peers in mainstream schools and even better than any other group of learners in the country. How can our ongoing commitment to learning and using te reo Māori, not just this week but all year, feed into a world where these children, and all tamariki in Aotearoa, are part of a wider community that values this taonga and models its use as best we can?

Definitely some food for thought – he kai mā te hinengaro. While the answer to these challenges isn’t as simple as tauiwi signing up en masse for beginner te reo classes (possibly to the exclusion of Māori trying to access those same services), what about the buffet of other freely available learning resources? Could we take some time to draw on YouTube, Spotify, Disney+, Māori TV, TVNZ, our many iwi radio stations, RNZ, Stuff, Instagram, Facebook, and of course our public libraries, to nibble at some new mātauranga? He kai pai tēnā ki te rangatira, nē?

Could we be a generation of Pākehā who don’t feed our own tamariki a diet of wilful ignorance to the linguistic and cultural richness of te ao Māori that’s just as freely available as sausage rolls and instant coffee at a kai whakanoa? We can engage with Māori history, language and culture to upskill and educate ourselves without bothering, or taking up the space of, Māori. In doing so, maybe we can help create more room for Māori to thrive, as Māori, in a variety of spaces – without having to constantly explain the basics to us.

So, grab a plate and get in line, because you know what they say: “E mua kai kai, e muri kai hūare. Those who are prompt eat food, those who dawdle eat only their own saliva.”

Ka mutu, kia whai hua Te Wiki o te Reo Māori ki a koutou. Kia toi te kupu, toi te mana, toi te aroha, toi te reo Māori!