The Justice Committee commenced the second day of Treaty principles bill hearings with two hours of oral submission.

In contrast to the massive first day of Treaty principles bill hearings, the Justice Committee heard just two hours of oral submissions in Room 3 of parliament this morning. Keeping in theme with Monday’s hearings, the beginning of at least four weeks of committee meetings, most submissions heard were against the bill.

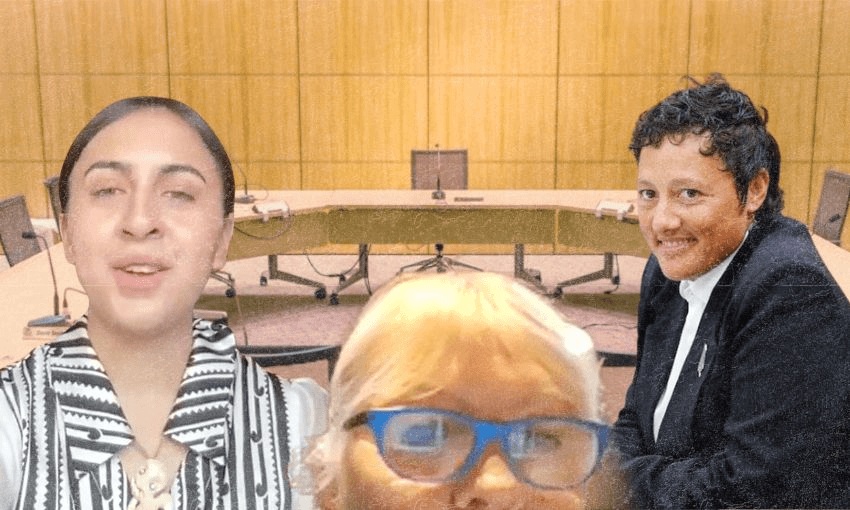

The committee in Room 3 had been bolstered – Tākuta Ferris and Joseph Mooney had moved from Zoom to real life, Rawiri Waititi was waiting to tap in when Ferris needed a break, and Willie Jackson was now sitting in next to Duncan Webb – but the public seats weren’t as full as on Monday, taken up only by journalists, Te Pāti Māori MPs and press secretaries. A few Te Pāti Māori, Green and Labour MPs have been switching places with each during the sessions, meaning Waititi, Mariameno Kapa-Kingi, Jackson and Hana-Rawhiti Maipi-Clarke also sat on the panel.

8am: ‘You’re out of sync with the best legal minds’

First up was YouthLaw Aotearoa’s general manager Darryn Aitchinson, who spoke on the legal needs of rangatahi Māori. “The type of issues that they face are connected to socio-economic disadvantage, which is itself connected to the impact of colonisation, and the legal issues that young Māori face include such things as unlawful exclusion from school, barriers to housing and barriers to accessing social security,” Aitchinson said. “Pretty fundamental rights and benefits young people should be able to access”.

Tai Ahu (Waikato-Tanui, Ngāti Kahu), president of Te Hunga Rōia Māori o Aotearoa, spoke against the bill on behalf of the Māori Law Society.

“The bill has already exacerbated institutional distrust by Māori towards the machinery of government,” he said. “It has already fostered cynicism in our political system and in the lawmaking process, and most importantly for Te Hunga Rōia Māori, it’s already caused many Māori to become sceptical of the law itself.”

He warned that the practical legal effect of the bill would change how Māori cultural values were recognised, the placement of young Māori in care, decisions on resource consent applications and the recognition of Māori language. “[This bill] has been cunningly and explicitly designed to strip the pre-existing rights of Māori,” Ahu said.

Ahu highlighted specific issues with each principle, saying the first ignored findings from the Waitangi Tribunal that Māori never ceded sovereignty, the second was described as “stripping” the recognition of tino rangatiratanga, and the third principle he said lacked acknowledgement in the barriers caused by the Crown that Māori already face.

Professor of economics Ananish Chaudhuri was the first to speak in support of the bill and said the debate around it was important to ensure Aotearoa remained multicultural. He argued that Māori had ceded sovereignty in 1840, as evidenced by “a long list of subsequent acts and laws that hold New Zealand to be an independent sovereignty”. “I may be wrong,” he added. “Āe,” replied Waititi from the public seats.

Lorraine Toki (Ngāpuhi), former chief executive of Ko tā Te Rūnanga-Ā-Iwi-O-Ngāpuhi, told the committee the bill altered the recognition of whānau and hāpu for the purpose of equality, but argued “there’s no equality in a society that alienates people from their whenua, from their reo, from their mātauranga, their taiao”. She said Ngāpuhi, Aotearoa’s largest iwi, will be further isolated by the bill, and asked for the bill to be more specific to the rights of hapū and iwi.

Asked by committee member Todd Stephenson of Act whether she believed it was important that people were treated equally and had equal protection, Toki said she “would like to think” she would be treated the same as her neighbour, regardless of race. “I don’t have that confidence,” she said.

Retired district court judge David Harvey said the bill should be passed, and that a referendum on the matter was necessary. He ended up copping the most brutal of the committee’s questions. “You’re out of sync with the best legal minds in this country,” Willie Jackson told him, after pointing out the more than 40 KCs – the “creme de la creme” – who have called for the bill to be abandoned. “I just can’t reconcile this, Judge, given your background and your status. Where does this put you in terms of the legal fraternity, because they seem almost unanimously against this bill?”

Harvey responded that “it bothers me not one whit if I’m out of sync with other people”. When he finished, committee chairperson James Meager asked the committee to refrain from making personal references to the submitters, given the amount of feedback he received following Monday’s hearings. “I receive enough emails as it is,” Meager said.

Raniera Kaio, general manager of health provider Te Rūnanga O Whaingaroa, said the bill itself was a breach of the Treaty, undermining its constitutional role and dismantling “the enforceable rights of Māori, leaving them subject to the Crown’s rule”. He referenced the history of land theft prior to and following the Treaty signing.

“This is the same blueprint being used today: the Treaty principles bill is not new, it is the latest chapter in a long history of orchestrated Māori subjugation,” Kaio said. “To this committee, I say this: history will remember you.”

9am: ‘Facebook comment section brought to life’

Former National Party MP and Thames-Coromandel mayor Sandra Goudie, who was last in the public mind for refusing to get the Pfizer Covid vaccine in 2021, spoke in favour of the bill. At the end of her 10-minute Zoom submission, Stephenson summed it up nicely: “there was a lot in that”.

With just her forehead shown on screen, Goudie argued there was “now an unprecedented emphasis and favouritism to Māori”, took aim at Māori businesses “only [paying] 17.5% of tax” (this rate applies to certain Māori authorities that meet certain criteria and requires the maintaining of a tax credit account), continually referred to Labour as the government, and questioned why there was no Waitangi Tribunal for non-Māori. Her comments got a heavy sigh from Webb and laughter from Waititi and Ferris. Her te reo Māori pronunciation prompted a few “oof”s.

Committee member Tamatha Paul of the Greens came in with a simple question: “What qualifies you to speak about Māori?” Goudie replied: “My own life experience gives me the right to actually speak about any matter or subject.” Waititi couldn’t help himself: “it’s your privilege”.

Perhaps the day’s most anticipated speaker, former Labour minister Kiri Allan, beamed into the hearings via Zoom. “This bill would eradicate the undertakings and promises that our forebears made to each other,” she told the committee.

She spoke of her former role as minister for conservation, and her responsibility to ensure Section 4 of the Conservation Act was honoured. The clause requires the department to give effect to the Treaty, which guarantees tino rangatiratanga over land, homes and taonga, and had replaced an earlier act that allowed confiscation of land from Māori who had “engaged in open rebellion against Her Majesty”. Should the Treaty principles bill pass, Allan said the clause would become “hollow”.

“I urge all members to oppose this bill and make the recommendation that all legislation contain a clause that each Act shall be interpreted and administered as to give effect to te Tiriti o Waitangi,” she said.

Economist John Milne supported the bill, telling the committee it would mitigate “sovereign risk”. He also quoted Sir Apirana Ngata’s interpretation of the treaty, which the parliamentarian believed indicated Māori had ceded sovereignty. Ngata’s interpretation of the Treaty is controversial – the Waitangi Tribunal and further historical research (Ngata’s translation was published in 1922) has argued that sovereignty was not ceded by Māori.

Council of Medical Colleges chair Dr Samantha Murton and board member Dr Jo Lambert (Waikato-Tainui) spoke against the bill from a health perspective. Murton posited that you wouldn’t give a baby and elder the same medicine, as one could kill the other. She argued that she wouldn’t give everyone with a uterus a pregnancy test, as not everyone with a uterus is able to conceive. “In health, we have to take in all things,” Lambert said. “We have to take in ethnicity.”

Maringi James (Ngāti Whakaue) was the last speaker of the morning. She submitted against the bill, and said listening to submissions in favour sounded like “Facebook comment sections brought to life”. While she understood the “fear of change”, she said “it cannot be justified for this bill”.

When it came to questions, Meager had two compliments for James: “Not only do you have a great surname, you have a great sense of style.” The camera panned to Hana-Rawhiti Maipi-Clarke, wearing the same shirt as James. “I don’t know how that happened,” Maipi-Clarke laughed.

Maipi-Clarke, who had replaced Ferris on the committee, asked James why she believed rangatahi deserved to be heard on this issue. “No matter how educated [we are] or how much we try and push back, we’re told we need to have a debate,” James replied, pointing out that many rangatahi who have grown up on their marae are used to these kinds of discussions. She said it was just a shame that the same level of focus hadn’t been applied to other Māori issues.