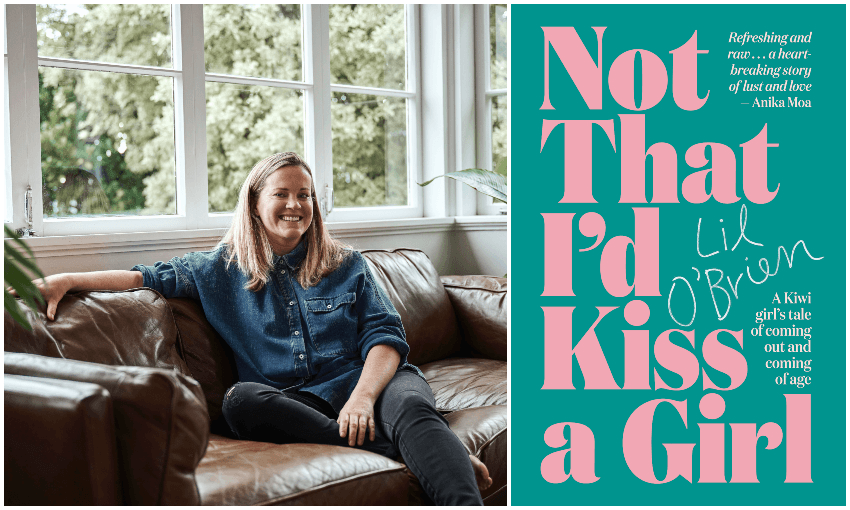

Tomorrow, Auckland writer Lil O’Brien releases one hell of a memoir: Not That I’d Kiss A Girl, the story of her coming out.

People tell me that I can make anything gay.

Sometimes they’re talking about physical things, like when I put on a plain white T-shirt then roll the sleeves over twice. But I think that mostly what they’re talking about is my way of looking. I have a queer gaze. It’s a way of seeing that influences what I notice when I step into a room full of people and it also means I can find something queer in almost anything.

Looking for representation of ourselves is something we all do, in everything from friend groups to television shows and books. We measure things up. “Are they like me?”

I learned to find myself hidden in the subtext from an early age, well before I knew I was gay. That’s how things mostly were in the 1990s and early 2000s. Queer people weren’t found on the page or the screen so much, but between the lines. So that’s where I taught myself to look and to find meaning.

I don’t remember the first time I read a book with a canon lesbian character in it, but I sure can remember all the female characters that I pegged as different, well over a decade before I would come to realise that I was a girl who liked girls.

I was drawn to a certain kind of female character in books, like the eponymous Alex in Tessa Duder’s series about a competitive swimmer. Or Pippy Longstocking – both illustrations of the capable tomboy. Even going as far back to when my reading was books with pictures, it was Phoebe and the Hot Water Bottles by Terry Furchgott and Linda Dawson that made my heart sing. A story about an orphaned girl who lived above her grandad’s pharmacy and had a zany collection of hot water bottles, and used them to put out a fire in the pharmacy all by herself one night.

The capable tomboy was a signifier for “queer woman”, before there were queer women to be seen. And so, I lived in and for the subtext.

Later, I would scour the pages of the Sky TV magazine, looking for film descriptions in the programming schedule that talked about things like “an intense friendship develops” or a “free-spirited woman moves into a small town and creates a stir”. When female characters became old enough to be sexualised, the queer coding I was looking for changed – there was still the capable tomboy, but there was also the over-sexualised woman, the manipulative woman or the lonely woman to keep my eye on. That’s what led me to the movies Cruel Intentions and Wild Things and Basic Instinct, and the other problematic representations of queer women in the late 90s that I adored. They were my representation when I was a teenager. And I loved them. The ones that troubled me were the teenage stories with the charismatic girl and her shy best friend who had a crush on her. I was that shy girl and maybe, even years before I came out, somehow I knew I was going to be the shy queer girl. And in those stories, that girl always ended up getting her heart broken – told she was a freak, or ultimately watching the best friend ditch her to start dating a boy.

We seem to have done slightly better with lesbian representation in the written word, from Virginia Woolf’s letters of longing to the pulp lesbian fiction of the 1950s and 60s, and the poetry and prose of all-around badass Audre Lorde. Sarah Waters has carried the historical lesbian fiction genre on her shoulders since the 90s, and as we ticked over into the 21st century, young adult fiction with queer female characters began its slow blossom.

Now there is a whole genre called “lesfic”, romantic fiction about wlw (women loving women), such as Something to Talk About by Meryl Wilsner, which I couldn’t stop reading even though it wasn’t that great, because it featured my favourite kind of romance: the slow burn. Lesfic prizes or perhaps demands a happy ending, and to go into why means looking into a history where tragic endings in gay narratives were pervasive, thanks not only to society’s opinion-at-large about queer people, but an actual censorship code that would have deemed a happy ending for two women as promoting indecent or immoral content. It’s part of the reason why Patricia Highsmith’s novel The Price of Salt, published in 1952, caused such a splash – it is considered the first happy ending in a lesbian novel, ever.

In the last year alone I have found some of my new favourite books with queer characters and my curated collection has exploded, made rich with Samra Habib’s We Have Always Been Here: A Queer Muslim Memoir, and Kabi Nagata’s manga series that begins with My Lesbian Experience With Loneliness. A story in which Kabi lays herself so bare and vulnerable that I had to put the book down and just breathe at one point, because I’d never identified so strongly with a person on the page before. Now those books nestle in next to other favourites, Zami: A New Spelling of My Name by Audre Lorde, and Written on the Body by Jeanette Winterson and Rubyfruit Jungle by Rita Mae Brown and The Miseducation of Cameron Post by Emily Danforth.

But we need to hear more queer New Zealand stories and voices.

Carole from The Women’s Bookshop in Auckland will tell you that she never has enough Kiwi books for her LGBTQ+ section, and she certainly doesn’t have any recent New Zealand tales about a queer woman.

“We’ve got a fair few books for the guys now,” she explained when I was in the store a few weeks ago. “Not so much for the ladies.”

But this month, I’m giving Carole something new for her shelf. It’s called Not That I’d Kiss A Girl, a memoir about my coming out as a teenager. It’s a book about love, and family, and identity, and fitting in. Hopefully it’s a book that will mean something to people like me, who have so desperately searched for themselves on the page and on the screen. I hope it will make queer or questioning people of all ages feel seen and understood. But I can’t lie and say I only wrote it for other people, because I also wrote it for myself. I wanted to give myself more of the representation I’ve searched for all my life. Maintext, not subtext.

Not That I’d Kiss A Girl, by Lil O’Brien (Allen & Unwin, $36.99) is available from Unity Books Auckland and Wellington.