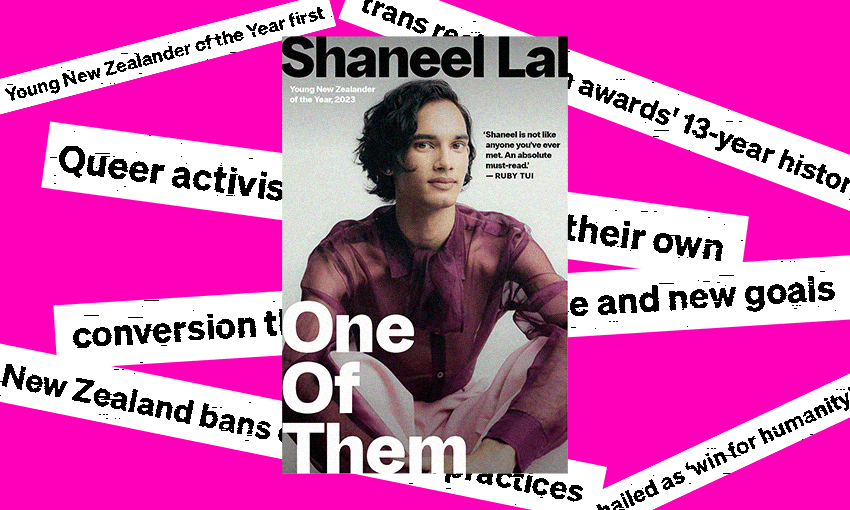

Sam Brooks reviews the new memoir by Shaneel Lal.

If you’re reading The Spinoff, you’ve probably heard of Shaneel Lal. If you haven’t read the writing of the “activist, writer, model and Young New Zealander of the Year” on our site, then you’ll at least be aware of their work as the cofounder of the Conversion Therapy Action Group, one of the most prominent forces behind the nationwide movement to ban conversion therapy, or from their column in the Herald on Sunday. They’re well-known enough, by this point, that they might have been granted that rare New Zealand honour: the mononym.

So it’s not surprising that, even though they’re only 23, they have written a memoir. Not only is Lal’s upbringing as a queer teen in Fiji – living through the trauma of being an outcast from their society and the torture of conversion therapy – notable, but their story is intimately, even inextricably tied, to the passing of the Conversion Practices Prohibition Legislation Bill. Their memoir not only gives audiences a crucial insight into the lived reality of a queer person living in Fiji, but also offers an on-the-ground retelling of that bill’s journey.

Those are the obvious things to take away from One of Them, though. The less obvious ones, which Lal weaves in with varying levels of grace, are the struggles that they’ve come up against as a queer person of colour. Many passages, and even entire chapters, are devoted to the ways in which they’ve made waves with the things they’ve said – there’s an entire chapter about Lal running for My Gay New Zealand, and another about a debacle where GayExpress (now YourEx) targeted Lal for comments about white gays. This is complex territory, and although Lal has more experience navigating it than most, it’s refreshing to see it covered in print, rather than posted about on Instagram stories, overly florid Facebook books, and flash-in-the-pan opinion pieces that end up in the dustbins of people’s internet history.

The book’s unqualified success is in the early passages, where Lal is telling the story of their upbringing, essentially the “before I was famous”. They tell the story of being labelled as gay and feminine – a “chakka” – very early on in life, and how that defined, and redefined their relationship to their family, in tragic and awful ways. The experiences of queer people in Fiji are something that I, frankly, have very little knowledge about, and to get this window into it wasn’t just fascinating, but chilling.

The value of stories like these are not necessarily how they’re told, but how they’re platformed. Lal’s experience is individual, of course, but phrases that reveal them reflecting, even as a young child, that they “do not have the canvas of a Pacific person” hit close to the bone. The queer experience is not monolithic – but the experience of being alienated not just from your society, from your family, from social structures in general, but from your own sense of self is something very easy to relate to, and Lal is an especially precise chronicler of their own experience here.

The opening passages of the book are so gripping that it’s no wonder the book loses momentum, and reach, the closer it gets to the present. The story of how the conversion therapy bill got passed is important, and it is interesting, but Lal talks more generally about that journey. The drama feels often third-hand, told through lengthy quotes from opinion pieces and interviews that Lal gave on TV: it can feel jarring when the story turns to Lal’s personal life, which ends up being infinitely more interesting, because it hasn’t been told before. Distance is the problem – neither Lal nor the reader necessarily has the distance from these events for them to be new information, so it often feels like retreading recently broken ground. If this story were to be told in a few years time, it might be easier for Lal to pick out which moments to prioritise, to put on the record, to intertwine with their own experience. So soon after the bill passed, everything feels equally important, and so it feels equally unimportant.

There’s an understandable defensiveness to the book, especially in that back half, where Lal finds their voice, and their ability to engage, persuasively, with systems and communities. In their 23 years, Lal has been the recipient of more hatred, online and in person, than most of us will ever encounter in a lifetime. No doubt they expected this book would lead to more hatred, likely from people who will never even read it. One defends when they expect to be attacked. Even so, it leads to passages where Lal is explaining their actions, explaining why they were right to think, speak or act in a certain way. It’s not that Lal is wrong, but it makes for an often dissonant reading experience: we’ve bought the book, we don’t need to be convinced of the author’s rightness, especially when those who actually read the book and engage with its rhetoric, are likely to agree, broadly, with Lal anyway.

It’s interesting, then, that the moments where the book really sings are when Lal puts their speeches on the page. The subtle distinction between their written voice – clipped, short sentences, building paragraphs brick by brick – and their oratory voice becomes extremely clear. When Lal speaks, as evidenced in several of their viral speeches, it’s like watching a skilled monologuist. It reminds you that speaking aloud, convincingly, is a skill, and not one that everybody possesses. There are volcanic ebbs and flows, a clear sense of how structure can be leaned into with vocal pyrotechnics, even of the subtle nature that Lal deploys.

Lal is an effective writer, as shown in their Herald column: they’re able to cut to the heart of a chosen issue or controversy with the brevity and speed that literal paper inches require. They can also turn in some absolutely banger turns of phrase – “e hoa gays” is a label that will resonate with anybody who has seen an Instagram photo featuring six people with identical haircuts, body types, and friend groups leaning into the same frame, faces sucked in. But when that voice is spread over a pretty lean 279 pages, it can feel a little breathless, as though Lal can’t wait to get to the next sentence, the next event in their life.

It’s perhaps telling that the last two pages of the book, where Lal is oldest, writing from the closest present to the future, are the best, and mostly richly written. One sentence feels like the exhale after the preceding couple hundred pages: “I do not have a sense of self, independent of the movement.” It shows their maturity, their willingness to reflect, and maybe even the willingness to pause.

Ironically, perhaps actually fittingly, One of Them ends up reading probably how it should: the diary of a 23-year-old with a very visible, very active public life, trying to balance and properly value their own inner life.

One of Them by Shaneel Lal (Allen & Unwin NZ $37) can be purchased from Unity Books Wellington and Auckland.