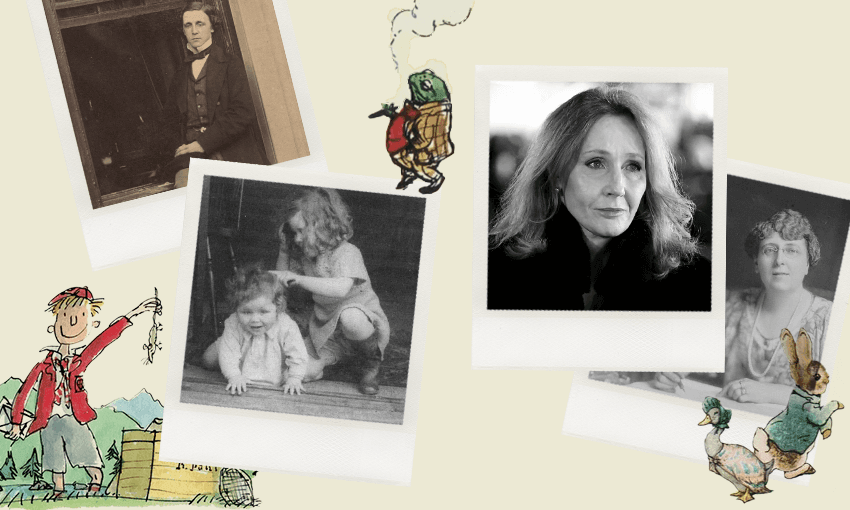

Summer reissue: You don’t have to live a haunting life of unparalleled grief and sorrow to be a great children’s author, but it helps.

The Spinoff needs to double the number of paying members we have to continue telling these kinds of stories. Please read our open letter and sign up to be a member today.

Content warning: This article mentions suicide and abuse.

It’s always been a cliche of children’s literature, that many of the greatest writers for children dislike children. Even those with children often seem to have a strained relationship with their offspring. While authors such as Dr Seuss, Raymond Briggs and Maurice Sendak have expressed a certain apathy towards the temporally challenged, disliking children and not wanting to be a children’s entertainer isn’t even remotely the same thing. After all, we don’t expect adult fiction writers to love and cherish the society of adults.

If there is a kernel of truth in the observation, it’s that loving the company of children is definitely not a prerequisite for being a good kids’ author, and certainly doesn’t make your work any better.

People who love children often write books like “the rabbit whose mommy loved him very much,” whereas people who respect the intelligence and humanity of children often write books like “the boy who had his teeth extracted by Dogman Jones” or “Paradise Lost II” (Philip Pullman). I’m not saying the two positions are mutually exclusive, but when it comes to children’s literature, I’d take a festering misanthrope over a doting grandparent any day.

However, as someone who has long been interested in the biographies of children’s writers, I have noticed certain commonalities. In my experience, the best children’s authors tend to fit one of four major archetypes.

- The nicest person who ever lived

- Evil

- Jolly alcoholic

- Filled with an unspeakable and haunting misery

Sure, the system has its flaws. I don’t know where Philip Pullman fits on this chart. But what does appear to be true is that many of the most beloved children’s authors have lives that you wouldn’t wish on your worst enemies.

Maybe everyone’s lives were just statistically more miserable back in the day: between various world wars, epidemics and economic depressions, it’s possible that this kind of biographical suffering is just par for the course. But it’s hard not to read the works of L. M. Montgomery and Kenneth Grahame and wonder if there’s some sense in which their children’s fiction is a literary compensation for the hardships and miseries they endured. Anyway, I’ll present the evidence, and we can let the psychoanalysts decide.

1. Diana Wynne Jones

I was shocked to read Reflections, an autobiographical account of Jones’s life and writing. I don’t know why I was so surprised to learn she had a miserable childhood, but her books have such an irresistible undercurrent of warmth and wit that it’s hard to square them with the deprivation she and her sisters endured.

That’s not to say all her books are “happy” by any stretch of the imagination. Particularly disturbing is The Time of The Ghost, which most closely mirrors her upbringing. One of the most common themes in her writing is children being unable to trust the adults in their lives, and having to take matters into their own hands. While it’s hard to imagine which contemporary children’s books this description doesn’t apply to, this wasn’t always the default, and Jones did a lot to liberate young audiences from the literary falsehood of adoring parents.

Diana Wynne Jones and her two sisters were raised by parents who fall squarely on the abusive/neglectful spectrum. Jones recounts how she and her young sisters were evicted from the house they shared with their parents and moved into a nearby lean-to with a dirt floor. There, the sisters were left to their own devices, often going cold and hungry. Diana and her sister both contracted juvenile rheumatism, which led to lifelong compilations with Jones’s heart.

The children had nowhere to wash, and as the eldest, Diana was punished when her mother discovered her sister Isobel had gone six months without combing her hair. There were a few close shaves in the shack, including one memorable incident where two of the girls almost hanged their sister while playing fairies and they almost burned the shack down several times by knocking over their only source of heating, a small paraffin stove.

Jones writes that “the cardinal sin we could commit was to be ill” and the girls were regularly sent to school with chicken pox, scarlet fever, and German measles. Jones suffered from appendicitis for six months until the doctor operated against her mother’s protestations. The little time they spent with their parents was full of acrimony. Although the recollections are softened somewhat by Jones’s sparkling wit, it’s hard to avoid the conclusion that the girls felt profoundly unloved by their parents, and were liberated only by the imaginative worlds they created together.

The excerpt also features two wonderful cameos by famously child-hating authors, including the girls being yelled at by Arthur Ransome, and beaten by neighbourhood crank Beatrix Potter.

Misery rating: 7/10

2. L. M. Montgomery

Of all the biographies in this list, the one that surprised me the most was L. M. Montgomery’s. Her most famous books, the Anne of Green Gables series, although personal favourites, definitely err towards the saccharine, and are powerfully optimistic, even as Anne navigates various heartbreaks and griefs. So it’s bracing to read Montgomery’s diaries, in which she is tormented by migraines and depression, “unspeakable horrors” and frequently describes her life as a “hell” full of suffering and wretchedness.

Montgomery’s mother died before she was two years old, and she was raised by her strict grandparents. She had a lonely and isolated childhood. As a young woman, she fell in love with a married man, who died of the flu a month after she broke things off. She later came to believe that her lifelong depression was caused by him haunting her from beyond the grave. She spent much of her adult life enmeshed in lawsuits against her publishers, with whom she had signed ill-advised contracts as a young and inexperienced author.

But a large part of her suffering came from her profoundly unhappy marriage to a mentally ill Presbyterian minister, who was continually haunted by the idea that he and his whole family were doomed to eternal damnation, drove erratically as if trying to kill his family, and retreated into dour, month-long silences that set everyone on edge. Montgomery frequently recorded that she wished she had never married him.

Together they had three sons, one of whom died in infancy, and Montgomery had a difficult relationship with her two adult children, particularly her son Chester, who was an unpopular loner with a reputation for indecently exposing himself. Towards the end of her life, she suffered from blinding migraines, constant nightmares, anxiety and a raft of other unpleasant symptoms including insomnia and vomiting. It’s extremely likely that Montgomery’s eventual death from an overdose of barbiturates was intentional.

“There has never been any happiness in this house – there never will be,” she wrote in her journal. “The present is unbearable. The past is spoiled. There is no future.”

Yikes.

Misery rating: 9/10

3. Roald Dahl

It shouldn’t come as a surprise to anyone to see Dahl on this list. He was famous for his mean streak and was nicknamed “Ronald the Rotten” by his wife. He resented his wife’s fame, and almost had his contract terminated by Random House for his self-aggrandising behaviour and unprofessional publishing demands. He was also a famous anti-semite, saying of Jewish people, “Even a stinker like Hitler didn’t just pick on them for no reason.”

His own life is well known, thanks to his many autobiographies, and it wasn’t exactly rosy. As a child, his sister died of appendicitis, and his father died a few weeks later of pneumonia. His nose was almost completely severed from his face in a car accident. He was bullied horribly at boarding school. He suffered catastrophic injuries as a second world war pilot. His four-month-old son’s baby carriage was hit by a taxi and flew 40 metres into a parked bus. His son, who barely survived, spent months in hospital with a crushed skull. Dahl’s daughter Olivia died of measles at the age of seven.

And yet, for all his suffering, Dahl seems to have retained a certain joie de vivre. You’ve gotta hand it to him.

Misery rating: 6/10

4. Kenneth Grahame

When it comes to the depressing biographies of children’s authors, a dead mother, an alcoholic father and a miserable boarding school experience seem to be par for the course. But as an adult, poor Grahame’s life went from bad to worse.

There has long been speculation that Grahame was either gay or asexual. It’s claimed he was a virgin until the age of 38 when he married an “intensely irritating and quite possibly unhinged” woman called Elspeth, who he had a creepy correspondence with, written in a kind of grotesque baby speak. His friends tried to get him to break off the engagement. When one of them asked if he was really going to marry Elspeth, Grahame is reported to have gloomily responded, “I suppose so.”

Big mistake. Elspeth was a kook, who apparently only allowed her husband to change his underwear once a year. They had one child together, nicknamed “Mouse”, who was allegedly spoiled rotten. Mouse exhibited a lot of strange and disturbing behaviour, such as lying down in the middle of traffic and “kicking girls in the head.” He nicknamed his father “Inferiority” and began calling himself “Robinson” after George Frederick Robinson, the man who had once tried to murder Grahame and been sent to Broadmoor.

At the age of 19, Mouse lay down on the train tracks and was decapitated. The Grahames spent the rest of their marriage in an intense mutual loathing.

Misery rating: 8/10

5. J. M. Barrie

J. M. Barrie’s life was haunted by misery. His older brother died in an ice skating accident, two days before his 14th birthday. Barrie spent the rest of his childhood trying and failing to compensate for the death of his mother’s favourite child.

Barrie married, but had no children, and divorced his wife after she had an affair. He made friends with the Llewelyn Davies family and was especially fond of their five sons, on whom the characters of Peter Pan and the Lost Boys were collectively based. He liked the children so much that when their mother died, Barrie FORGED HER WILL in order to get custody of the children.

In 1902, Barrie wrote a semi-autobiographical novel called The Little White Bird, in which Peter Pan makes his first appearance. The main character of the story becomes enamoured by a little boy and tries to steal him away from his mother, by inventing the story of Peter Pan in order to enchant the child.

His “child thieving” tendencies and unfortunate association with Michael Jackson’s Neverland have understandably led to some unsubstantiated posthumous speculation about whether Barrie was a paedophile, or just an ordinary, run-of-the-mill kidnapper.

Two of the Llewelyn Davies boys died in their 20s: one during the first world war, the other in a suspected drowning suicide, with a close male “friend.” Barrie never recovered from the deaths of the two younger boys, who were his particular favourites.

“It is as if long after writing ‘P.Pan’ its true meaning came to me,” he wrote in later years. “Desperate attempt to grow up but can’t.”

Misery rating: 6/10

6. J.K. Rowling

Enough said.

Misery rating: TBC

7. Lewis Carroll

Was Lewis Carroll, author of Alice in Wonderland, a paedophile? I don’t even want to get into this one. Attitudes to nude photography and “marriageable ages” have changed a lot since the Victorian era, but go and read the “Controversies and mysteries” section of his Wikipedia page if you want your eyebrows raised.

Perhaps more fun is the admittedly outlandish speculation that Carroll was Jack the Ripper.

Misery rating: unable to substantiate

8. Hans Christian Andersen

Hans Christian Andersen, author of fairy tales such as The Little Mermaid, was a pretty weird guy. He was born into extreme poverty and hardship and taunted mercilessly by a school headmaster whose presence haunted his nightmares for the rest of his life. His love for both men and women was mostly unreciprocated, although he kept a surprisingly thorough masturbation diary.

While the hardships he suffered are less acute than some of the other authors on this list, it’s hard not to read his biography and come out with a prevailing sense of melancholy. Apparently, Dickens modelled the character of Uriah Heep after Andersen, after a disastrous stay at Dickens’s house. Enough said.

Misery rating: 4/10

9. A. A. Milne

Perhaps we can forgive Milne for being a tad touchy after enduring years of relentless bullying at boarding school, and his experience during that “nightmare of mental and moral degradation, the war.” (Like Tolkien, Milne was present at the Battle of the Somme.)

But perhaps the most brutal part of his life was his estrangement from his son Christopher, on whom the character of Christopher Robin was based. Christopher famously came to resent his namesake character after being relentlessly and inventively bullied by his schoolmates who quickly discovered his true identity. The exploitation of his name must have stung, especially considering Milne was something of an absentee father. Christopher later wrote that his father “had got where he was by climbing on my infant shoulders, that he had filched from me my good name and had left me with nothing but the empty fame of being his son.”

Christopher later married a cousin who belonged to a branch of the family his parents had already fallen out with, and this only deepened their mutual estrangement.

In addition to his own character/son turning against him, Milne spent most of his life feeling aggrieved that he was remembered for his children’s writing when he longed to be taken seriously as a political commentator. It didn’t help that his Christopher Robin poems were mercilessly lampooned by his peers, including P. G. Wodehouse. Sad.

Misery rating: 6/10

10. David Walliams

David Walliams is evil. I have no evidence to prove this. I just know it in my heart. One day I’m going to be vindicated and I’ll never have to sell another one of his stupid books again.

On the other hand, he doesn’t actually appear to write the books published under his name, so is it even fair to include him on a list of children’s authors?

Misery rating: let’s wait and see

Have I missed anything? Let me know in the comments.

First published September 30, 2024.

If you or someone you know is in need of support, get in touch:

TAUTOKO Suicide Crisis Helpline – 0508 828 865

1737 – Need to talk? Free call or text 1737 any time for support from a trained counsellor

Lifeline – 0800 543 354 – free text 4357 (HELP)

Samaritans – 0800 726 666

Youthline – 0800 376 633, free text 234 or email talk@youthline.co.nz or online chat. Open 24/7.